Welcome back to Wall Power. I’m Marion Maneker.

I’ve told you

a number of times that the art market is long overdue for a historical turn. Over the last few years, there’s been a long oscillating cycle between infatuation with young artists (the next big thing) and rediscovery of historical talent—a dialectic that reflects the behaviors of collectors during a downturn. Tonight, I’m going to take you to David Zwirner gallery for two different historical shows that illustrate the trend toward rediscovery.

But first…

|

- Sotheby’s $16.8 million in South Asian sales: Sotheby’s sale of mostly Indian modern art was a huge success, with record prices for Jagdish Swaminathan and Jehangir Sabavala—in addition to final prices well above the estimates for Francis Newton Souza, Ganesh Pyne, and M.F. Husain. Sotheby’s top lot was Swaminathan’s Homage to Solzhenitsyn, which was estimated at $1 million but sold for $4.6 million with fees. Sabavala’s The Journey of the Magi was estimated at $600,000 but sold for $2.7 million with fees.

Souza’s Oriental City was estimated at $350,000 but sold for $1.17 million. Pyne’s untitled painting was estimated at $200,000 but got bid to

$787,400. Half a dozen works by Husain, one of the most prolific Indian painters of his generation, were sold at prices well above the estimates, including Woman in Red, which was estimated at $100,000 and sold for $635,000.

- Bonhams wasn’t left out of the Asian art bidding

frenzy: A blue-and-white 18th century Qianlong vase decorated with a red dragon was offered in Bonhams’ Chinese ceramics and works of art sale yesterday with an estimate of $400,000. Only one comparable work is known to exist, and it is in the collection of the Beijing Palace Museum. That might help explain why 10 bidders drove the final price to $3.7 million with fees. Another Imperial vase, this one from the Yongzheng reign that preceded Qianlong, was also estimated at $400,000. It, too,

was decorated with dragons, but bidder enthusiasm only carried it as far as $1.75 million with fees. The entire sale brought in $9 million, with an 82 percent sell-through rate.

- We want to hear from you: Julie Davich is in the Netherlands at TEFAF. But she’ll be in London tomorrow. If there’s anything you think she ought to see, please let her know at JDavich@puck.news. This would also seem like a good time to remind you to get in touch with me if you think we’re missing an important art world story. (Just not what might have happened at that New Yorker party.) You can reach me by replying to this email or at +1.917.825.1391 on SMS, Signal, and WhatsApp. Give it a try and I’ll text you back.

|

Now let’s get to the main event…

|

|

|

Two shows offer a vision of accelerating art market trends through the works of

Léon Spilliaert, and the chummy Bauhaus trio of Anni and Josef Albers and Paul Klee.

|

|

|

Art market trends build slowly, and then sometimes seem to come together all at once. That’s

what appears to be happening with the Belgian symbolist painter Léon Spilliaert, who in October had a work on paper sell at auction for $1.3 million—more than twice his previous high price of $559,000, set just the year before. Now, Spilliaert has a show of his haunting early 20th century works up at David Zwirner gallery, organized in collaboration with Agnews, Brussels.

As an influence on two other Belgian painters who also happen to be in Zwirner’s

stable—Luc Tuymans and Michael Borremans—Spilliaert is anything but antiquated. Zwirner partner David Leiber explained to me that the largely self-taught artist “had one symbolist foot in the 19th century and the other was stepping into the 20th, on a windy path toward abstraction.”

The heart of the show is a series of beach scenes and waterfront vistas from Spilliaert’s native Ostende—moody to the point of abstraction, and made mostly in

1908 using an innovative wash of India ink. Indeed, it was one of these works (though it’s not in the show) that made that record price in the fall. Another similar work sold in London earlier this month for $872,071, indicating that the earlier jump in price wasn’t a fluke. These spectral scenes—Spilliaert was an insomniac and Nietzsche fan who walked through seaside Ostende at night before sitting down to work—are hitting a nerve with collectors, and that’s one of the reasons

Zwirner has brought them to New York. “One of the goals of the exhibition was to broaden the market appetite for Spilliaert’s work,” Leiber told me, “which over the recent years has especially favored his brooding, almost existentialist self-portraits.”

One self-portrait in the show depicts Spilliaert seen through a mirror with silver, electrified hair. You’ll recognize it, even if you’ve never seen it before, because David Lynch used the image as inspiration for the

poster for Eraserhead. Hitchcock was a devotee, as well.

This won’t be the last you hear of Spilliaert, either on the market or in an American museum. There’s talk of a big monograph show on the horizon here in the U.S., but let’s remember that we’re measuring in museum time, which means we won’t be able to see the works until the tail end of the decade. The last major show of Spilliaert’s work was held at the Metropolitan Museum in 1980, beyond the living

memory of many contemporary collectors. And it makes a difference to see these works in person, rather than a reproduction in a book. Beyond the selfies, there are some surprisingly light-hearted and colorful images, even a few depicting blue skies, bright open rooms with pink furniture, bourgeois girls at play, and ladies in repose. But there’s also an image of hanged men dangling from a tree that’s darker than a New Order song.

|

Léon Spilliaert, Les Pendus (The Hanged) (1912)

|

While you’re at Zwirner, you’ll want to see Leiber’s other effort, Affinities: Anni Albers,

Josef Albers, Paul Klee, up now at the gallery’s West 20th Street location. Nicholas Fox Weber has curated a show of work by both Anni and Josef Albers and their teacher, neighbor, and mentor Paul Klee. The folks at Zwirner are quick to point out that there has never been a show of just the three artists’ work together: They have all appeared in historical or thematic shows about Bauhaus, the influential and consequential

Weimar school of art and design where they all met and taught, but this is the first show focusing on these three—whose lives intertwined in the 1920s to lasting effect for each. Since Weber is the director of the Josef and Anni Albers foundation, he has access to works that no one else might get.

The artists were neighbors who all taught at Bauhaus once it moved to Dessau in the latter half of the 1920s, and met when Anni took a weaving course from Klee. The most enigmatic of the three

artists, Klee was a member of Der Blaue Reiter group, influential as a teacher but fairly singular as an artist. His work was admired by Picasso, but it looks nothing like the cubism, expressionism, surrealism, and abstraction it is often connected with. Anni, in particular, expressed a deep debt to Klee for the example of his work.

There’s a lot going on in this show. Weber and Leiber took pains to search out and secure works by Klee that would help illuminate the work

of both Alberses, of whom Josef is the more famous. You’ll be familiar, at least in a passing way, with Josef’s Homage to the Square series of concentric color block paintings.

|

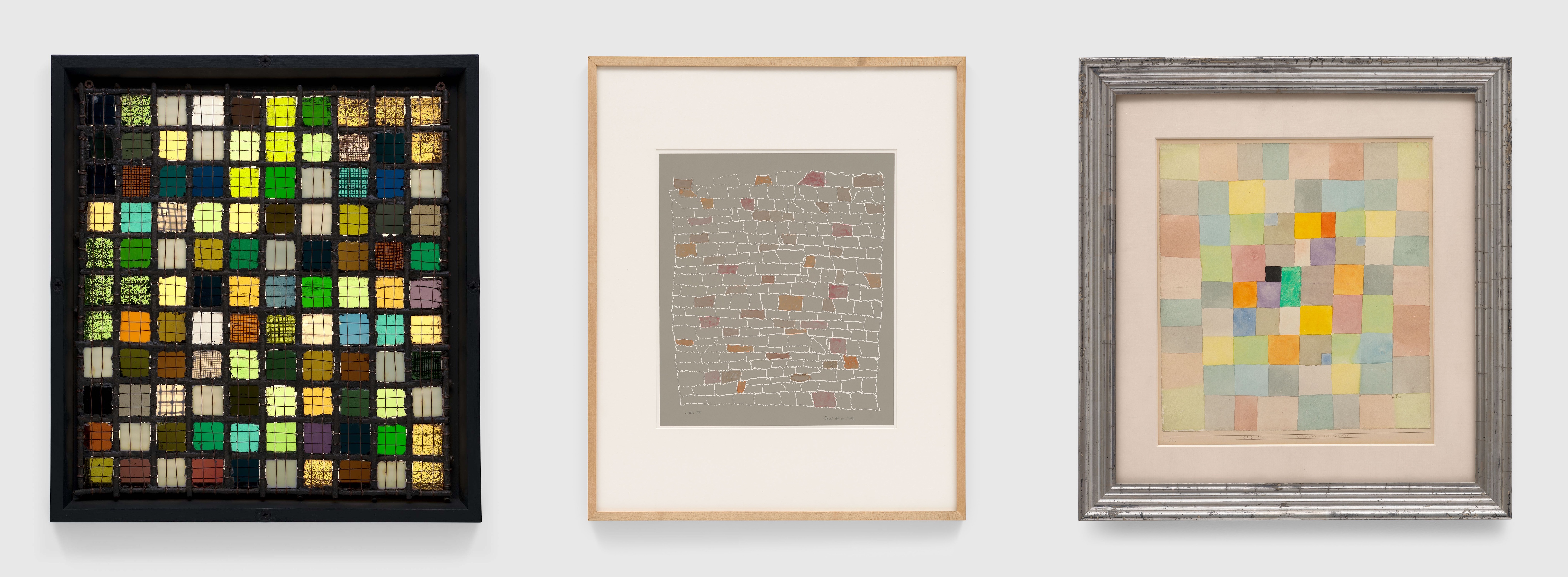

From left: Josef Albers, Gitterbild (Grid Mounted) (1921-22); Anni Albers, Wall IV (1984); Paul Klee, Nördlich-winterlich (Northern-wintry) (1923)

|

Anni was long treated as the junior partner in the family, but her work in textiles is becoming

increasingly recognized as that medium explodes in importance. This November, in fact, there will be a major retrospective of her work—Anni Albers. Constructing Textiles—at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern. “Neither Paul Klee nor Anni nor Josef imitated one another, but they shared certain goals,” as Weber put it in his statement about the show. “Their art was a celebration—of

color, of form, of the value of art that was not a personal revelation but was, rather, an ode to the universal.”

The universal here is color and form. Weber toggles between these two poles, and the three artists, in exciting and inventive ways. The show contains some rare glass works by Josef Albers illuminated by 21st century LED technology, like Gitterbild (Grid Mounted), from 1921-22, which mimics stained glass windows and anticipates Gerhard Richter’s

color-chart windows for the Cologne cathedral. Not far from that work hangs Anni’s late watercolor from 1984, Wall IV, made with a trembling hand (she was 85 years old by then) and “illuminated” with subtle washes of color. On either side, gridded watercolors by Klee hang, exemplifying the artist’s hard-won mastery of color.

Again and again in the show, Weber makes connections among the three artists that will seem obvious to the viewer, but mask the hard work of matching works

and securing loans. The paths of the three artists diverged after their time together in Dessau. The growing Nazi pressure on Bauhaus would eventually close the school in 1933; the same year, the Alberses immigrated to America, thanks to a chance meeting with Philip Johnson. (Anni Albers was Jewish; remaining in Germany would have been fatal.) Earlier, Klee had left for Düsseldorf before returning to Switzerland. For a time, Anni and Josef taught at Black Mountain College in

North Carolina; Josef would move to Yale in 1950 to run the design department and begin his now-classic Homage series.

After viewing this show, it’s hard to know which way your interest and curiosity will point: toward the Bauhaus’s attempt to collapse fine art, craft, and design into one kind of art for the industrial age? Down a rabbit hole of Klee rediscovery? Over to Josef’s color theory? Or back to Anni’s remarkable insistence that textiles can function as discrete works of art?

Maybe it’s all four.

|

The Wall Street Journal was on fire over the weekend with a raft of stories

about the art world. Fresh off Mary Rozell’s star turn in the Financial Times—which gave a detailed tour of her Brooklyn town house and pocket biography of her route to becoming the head of UBS’s massive 40,000-item art collection—the Journal took a close look at the

unexpected 13,500-piece art collection that UBS ended up acquiring when it absorbed Credit Suisse in 2023.

The two banks came to art from very different directions. Credit Suisse primarily bought Swiss artists to decorate offices in Switzerland. Although UBS’s art collection has broadened out under Rozell to emphasize the bank’s role in supporting artists directly, the Journal article does admit that there’s a perk to rising through the bank’s ranks. “Art is also a big deal in

the C-suite,” the story says, “where picking out paintings for an office is considered a senior executive rite of passage.” The bank doesn’t need 53,500 works of art to decorate offices and give its star executives a sense of self-importance. So it is Rozell’s job to make sense of the massive trove of art from which, she tells the Journal, she’s likely to sell hundreds of pieces.

The bank has already held sales of lower-value art to employees and made donations to

museums. There is a whole collection of surprisingly valuable ship models inherited from previous mergers that are being fed to the market slowly. And as with all mergers, there’s a winner: The Journal’s story ends by telling us that UBS’s art has prevailed over Credit Suisse’s in the battle for wall space in the new, combined institution.

Also on Friday, the Journal

published a lukewarm review of Blake Gopnik’s biography of Albert C. Barnes. “Mr. Gopnik ably illustrates the story of Barnes’s rise and his collecting, spiriting the reader along as Barnes flits from passion to passion, feud to feud,” Benjamin Riley writes. “But though

Mr. Gopnik does his best to present Barnes as a visionary collector with a novel conception of art, we leave the book unsure exactly of Barnes’s views, despite the collector having spilled pages of ink attempting to elucidate his theory.”

Why is this important? The Barnes Collection is fascinating, but also mystifying and mildly infuriating—replicating Barnes’s idiosyncratic theories about art and entrapping these extraordinary works within it. Every time I go, I’m reminded of how

perverse it is that one rich man, who owned these paintings for a few decades at most, has been able to dictate how they are seen forever. (Barnes died in 1951; among the details of the trust he left were a prohibition on loans, color reproductions, and rearranging the art, not to mention limiting public access.) The Barnes only recently won the right to put on temporary exhibitions within the museum, which will allow the art to be presented in a different art-historical context. If there’s no

coherent and lasting theory behind Barnes’s bizarre arrangements—and trust me, I haven’t found it yet—doesn’t that suggest the museum ought to be given more leeway to do justice to the art, over Barnes’s domineering and pugnacious ego?

|

Tomorrow’s another installment of the Inner Circle. Thanks to the many of you

who have signed up. And thanks to those of you who have offered feedback with your views on our decision to move proprietary market data to this tier. Remember, Puck’s Inner Circle subscription is still cheaper than comparable art market newsletters. (When I first started charging a subscription fee for the data content, that price was more than three times what we charge for the Inner Circle today.) If you’re serious about understanding where the art market is heading, an Inner Circle

subscription is a bargain.

Well, there you have it for today,

M

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and

insight to explain the backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|