|

Hеllo, and welcome back to Tomorrow Will Be Worse!

Yes, that's two emails in two days. Earlier this week, I wrote about the Virginia governor’s race and the extent to which culture wars and race played into the Republican victory there. Now, I want to take you somewhere a little different from what you’re used to reading about on TWBW and at Puck.

By the way, if you’re enjoying these free previews of my work, please consider subscribing to read the full thing. Puck members also get access to events, podcasts, and unlimited access to all of my fantastic colleagues—Baratunde Thurston, Matt Belloni, Tina Nguyen, Dylan Byers, Peter Hamby, and many more.

Kirsten Powers, who went from liberal on Fox News to anti-Trump voice on CNN, explains what happens when the shouting matches end, the cameras turn off, and you’re stuck in the green room with Santorum. And how to handle it all, and more, with a little grace. About five years ago, I went to a conference called the Faith Angle Forum, hosted by the Faith & Policy Center, a conservative-leaning Washington think tank. The Forum is a nice little getaway where journalists and faith leaders and scholars can meet and learn from each other. I was massively skeptical, as this is very much not my jam, but my very close friend, the New York Times Magazine political reporter Robert Draper, insisted that I attend. It’ll be interesting, he said.

And it was. I remember being transfixed by Albert Raboteau, who taught religion at Princeton, delivering a lecture about how enslaved people in America flipped the power dynamic on its head by forgiving their tormentors, even when they had not asked for forgiveness. In extending forgiveness, they, who had nothing, had the power to bestow something important and other-worldly, thereby shifting the relationship between enslaved and enslaver, if only for a moment.

It was a moving lecture, but I guess I’m just an Old Testament kind of girl. I’m an extremely secular person, but I was raised in a religious tradition where the transgressor has to ask for forgiveness—and then never do that thing again—to be forgiven. And having celebrated Passover more than a few times, I’m pretty sure that my people still haven’t forgiven the Egyptians for enslaving us thousands of years ago. I couldn’t imagine forgiving my torturer for something as horrific as slavery in America ever, let alone in the moment of suffering. Anyway, I found the lecture—and Raboteau’s almost hypnotic delivery—fascinating.

Robert found the conference interesting, too, but for other reasons. It was where he met Kirsten Powers, who was then the lone liberal voice on Fox News, and is now a political analyst on CNN—and is now Robert’s partner. Through Robert, Kirsten and I also became good friends, and I often felt pride seeing Kirsten go viral for throwing death-ray side-eye at Trump enablers on live national TV during the chaotic years of the Trump administration. Those years were difficult for her, as they were for many of us. It was hard to be a journalist when the administration and its allies were constantly kicking you in the teeth and generally acting like a wrecking ball. It was hard not to lose your cool on Twitter, and then not be embarrassed (or worse) by the consequences.

But Kirsten, who is Christian and deeply connected to her faith, grappled with it differently than I did. (I’m not even sure how I grappled with it, but that’s not really the point.) The result is Kirsten’s new book, Saving Grace, about how extending grace (in the Christian sense) to one’s political enemies is a powerful way not only to lower the temperature of our political debate, but also to preserve one’s sanity. Grace, Kirsten writes, “is what we most love to receive, but often the last thing most of us want to offer.” I’m still not sure I agree with Kirsten on everything in the book, but it challenged me and my assumptions in profound ways. And I got goosebumps reading the chapter called “When Grace Runs Out,” about what’s come to be called “cancel culture” and how perpetrators of injustice abuse the concept of grace by demanding it of the people they harm. Anyway, here’s our conversation, edited for length and clarity. I hope you enjoy Kirsten’s book as much as I did.

Julia Ioffe: Before we get into all the questions I have for you about this book, could you please summarize what you mean by grace?

Kirsten Powers: I use the Christian paradigm of grace, which is unmerited favor, meaning there’s nothing you can do to earn it. It is something that you just deserve just because you exist. But the book is meant for everybody, and I think it’s accessible to people of all faiths—and no faith. I think in the United States, we think that everybody has to earn things. They have to in some way do something to deserve my favor. When I started writing the book, people said to me, Well, yeah, I can give grace to people who basically think like me, and maybe they make a mistake. I can give them grace, but I’m not going to have grace for those other people. Well, that’s not really grace, because you just gave me a reason that you’re giving it to them. It has to be something that they didn’t do something to deserve. That said, it can be a very triggering word because of the way that I think it’s been weaponized.

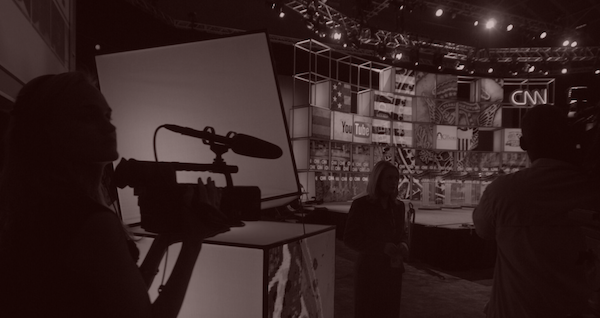

You talked in the book about how you went searching for this because of what you call “the fight-club arena of American politics and media,” in which you’re a star player. You pull the curtain back on what it’s like to be there, at CNN, after the cameras go off and you’re in the elevator and the Trump defenders tell you, Oh, I have to do this because he can’t tolerate any criticism. Or when Rick Santorum tells you in the green room that he thinks women accuse men of sexual assault to get rich.

I hit a wall, basically. I would say it happened towards the end of 2018, after the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings. I just was miserable and I was physically unwell. I had chronic fatigue. I had chronic pain, I had clinical anxiety. I broke my tooth from clenching my jaw too hard. I was just utterly miserable and I realized, this just isn’t sustainable. I realized that basically the soundtrack in my head about other people, the way I was talking about other people, the way I was sometimes behaving, particularly on social media, was not aligned with my values. It wasn’t really who I said I was. I’m a Christian. I believe in loving your neighbor and even loving your enemies. And I was so far removed from that. And if I’m being totally honest, I didn’t even want to do it. I asked myself, who do I want to be? Because this isn’t it...

FOUR STORIES WE'RE TALKING ABOUT The indie film industry is notorious inside Hollywood for penny-pinching financiers, lax on-set managers, cheap hires and poor on-sent conditions. MATT BELLONI Culture wars work, and Glenn Youngkin just rode the so-called "critical race theory" issue straight to the governor’s mansion. JULIA IOFFE A candid conversation with Eric Schmidt about A.I., his relationship with Biden, and how “woke-ism” has changed the C-suite. TEDDY SCHLEIFER Apollo has long been identified with its co-founder Leon Black. Now his successor Marc Rowan is on a mission to change that narrative—pronto—and to make a killing in the process. WILLIAM D. COHAN

|

-

Join Puck

Directly Supporting Authors

A new economic model in which writers are also partners in the business.

Personalized Subscriptions

Customize your settings to receive the newsletters you want from the authors you follow.

Stay in the Know

Connect directly with Puck talent through email and exclusive events.