Welcome to Wall Power—the Inner Circle edition. In this special weekly issue, as you

know, we spend some quality time with the most influential and informative leaders in the art market. I’m Marion Maneker, your matchmaker.

Tonight, I sat down with Ed Dolman, the outgoing executive chairman of Phillips, to talk about his 11-year tenure at the nice-guy auction house. During this period, as you’ll hear him say, Phillips was able to triple revenue in an era of shrinking auction volumes. We’ll get into the weeds with Ed in a minute.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

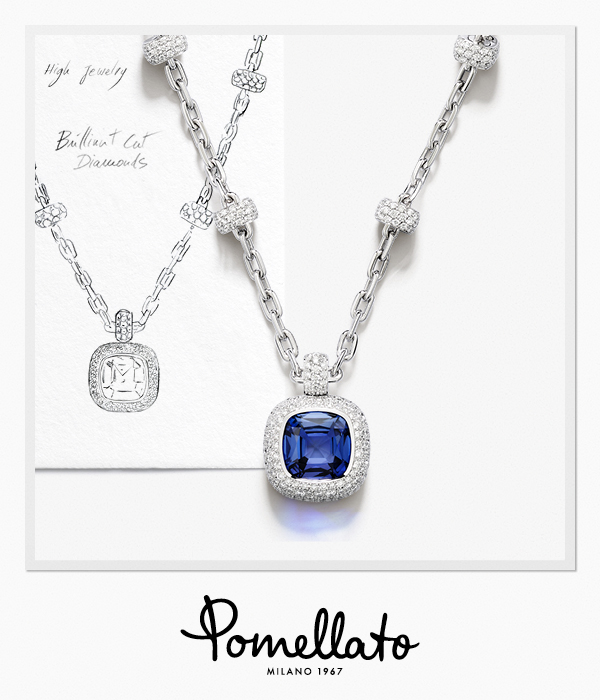

At the intersection of artistry and innovation lies Nudo, Pomellato’s most iconic creation. Each

Nudo piece is a miniature masterpiece, where design creativity, expert craftsmanship, and gemstone mastery meet. The Nudo High Jewelry collection embodies Pomellato’s unique vision of precious jewelry, combining the collection’s signature lightness and wearability with new levels of creativity and craftsmanship.

LEARN MORE

|

|

|

- American art continues to attract bidders: Christie’s Modern American Art sale last week hauled in $14.2 million, with an impressive number of works seeing very strong bidding above the estimates. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Red Canna, from 1919, was estimated at $1 million, but sold for $2.8 million. Thomas Hart Benton’s

The Chute, Buffalo River Above Willems Landing, from 1970, was estimated at $120,000, but sold for $529,000. Marvin Cone’s Hill Farms, from 1936, sold for more than $400,000 against an estimate of $150,000. Charles Ephraim Burchfield’s The Promise of Spring, from 1956, was estimated at $120,000, and bid to a premium price of $315,000.

And then there was Armin Hansen’s The Lonesome Salmon Trawler, from

1920, which was expected to fetch only $70,000, but bidders took to more than $300,000. Doris Emrick Lee’s Butterfly Catchers, from 1950, sold for almost $290,000, even though the estimate was a mere $20,000. Henrietta M. Shore’s White Radiance was estimated at $40,000, only to sell for $275,000. Agnes Pelton’s Intimation II, from 1934, estimated at $15,000, was sold for $126,000. There were more solid

overperformances, but it wasn’t all strong sales: Seven-figure lots from Arthur G. Dove, Stuart Davis, and O’Keeffe failed to find buyers.

- The Rashid Johnson ideal: I really enjoyed the mid-career retrospective of Rashid Johnson’s work at the Guggenheim. Among other things, the progression up the museum’s ramp lends itself to an artist whose work is heavily conceptual early on but then

evolves into bold mosaics and paintings with real impact. At the top of the spiral, Johnson’s art comes together in a coherent mix of his three-dimensional grid environments, which are perhaps his most conceptual works, and a selection of his very recognizable paintings.

Johnson was until recently a trustee of the museum, and the Guggenheim’s leadership might have been a little over-boosterish to claim in the press preview that the installation of palm trees suspended in the

rotunda was comparable to the hanging gardens of Babylon. That said, Johnson is a really good artist who tackles big ideas while making work you would want to live with. His market seems to agree, but it hasn’t overheated—whether because of his gallery’s well-known penchant for pushing up primary prices, or because his production is significant enough to satisfy collectors, who don’t have to bid up scarce work on the secondary market.

A quick glance at ARTDAI’s data is instructive. The

top price for a Johnson work at auction was the $3 million achieved in November 2022 for the white Surrender Painting “Sunshine.” Two years later, Triptych “Box of Rain” made $2.7 million. (The seller was Laurent Asscher, who’s just opened a private museum in Venice.) Johnson’s auction volume during the past

four years has been remarkably steady, with around $12 million in art selling publicly in 2021 and 2022, dropping down to $10 million in each of the past two years. By accident or design, Johnson seems to be escaping the trap of a market that runs away from his ability to keep up with it.

|

|

|

The auction house leader opens up about grabbing market share from the

Big Two, expanding into Asia, and the Matisse bronze sale that established Phillips as a player in contemporary.

|

|

|

Ed Dolman was just 39 years old when he became C.E.O. of Christie’s,

in 1999, and his first few seasons on the job were tough: The departure of his immediate predecessor, Christopher Davidge, was followed in short order by the revelation of the price-fixing scheme he had cooked up with his counterpart at Sotheby’s. Dolman would become the fixer—running the company for 12 years as the art

market recovered from the scandal. During his tenure, he endured the dot-com recession and 9/11, and saw contemporary art rise to dominance.

A turn atop one of the industry’s two leading firms would be considered a wildly successful career for anyone. But Dolman wasn’t done: He left Christie’s in 2011 to chair the Qatar Museums Authority. Three years later, he returned to the auction business by taking the helm of Phillips.

Over the past decade, Dolman has recruited talent from both

Sotheby’s and Christie’s, led Phillips’ expansion into Asia and the luxury goods market, and built new headquarters in London, Hong Kong, and New York. Earlier this month, we spoke about this phase of his career. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

|

“There

Was Room for More Than Two Players”

|

Marion Maneker: What were your impressions of

Phillips when you arrived? What were the key things you needed to focus on?

Ed Dolman: I’d always seen Phillips as an organization with huge potential that wasn’t necessarily being fulfilled. Deals in the market were becoming increasingly financially driven, rather than relationship-driven. The generations of relationship-driven business that Christie’s and Sotheby’s had, because of their long history, were becoming much less important. I’d also seen this tsunami of

global interest in contemporary art.

Phillips was ideally positioned to be a little bit more aggressive in its competition against Sotheby’s and Christie’s. So I thought it was a perfect vehicle, at the end of my career, perhaps, having had all this experience, to see what we could do in terms of creating a little bit more choice for clients in the market, and to try and exploit that interest in contemporary art.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

At the intersection of artistry and innovation lies Nudo, Pomellato’s most iconic creation. Each

Nudo piece is a miniature masterpiece, where design creativity, expert craftsmanship, and gemstone mastery meet. The Nudo High Jewelry collection embodies Pomellato’s unique vision of precious jewelry, combining the collection’s signature lightness and wearability with new levels of creativity and craftsmanship.

LEARN MORE

|

|

|

And that’s because of Phillips’ role as the house that would launch emerging

artists’ markets?

Exactly. Phillips and Simon de Pury and Daniella Luxembourg had, with Bernard Arnault’s help, completely repositioned Phillips’ brand, I think, extremely effectively, to associate it squarely with contemporary art—the work of living artists. Which was the perfect thing for them to do at that time. In my early years at Christie’s, when I was working for the furniture department in London as a specialist, Phillips

was a major competitor of Sotheby’s and Christie’s as a general auctioneer. So I realized that there was room for more than two players.

You persuaded the auctioneer Aurel Bacs to bring his watch business to Phillips. Tell us about your views of the luxury market.

The Phillips watch department was really the product of my long relationship with Aurel, because I’d worked with him when I was at Christie’s. He was the one person in the auction

business I’d ever come across who literally could control a market. We were able to make Aurel a proposition at Phillips that was attractive, and he came and absolutely delivered. The watch department was the first department to represent Phillips in Asia, our sort of beachhead into China. They were, and remain, one of the single most profitable categories in the art market.

That goes to the promise of luxury as a whole. I do think jewelry is important for Phillips, and we constituted a

new department, effectively, that started sales in Geneva just a couple of years ago under Benoît Repellin. He’s doing an amazing job for us, and we are continuing to make strides.

We’ve resisted embracing with great enthusiasm some of the other areas of the luxury goods auctions. We don’t do handbags, for instance; we don’t do wine. Those choices have been deliberate, because we wanted to focus on our main categories. If you’re in what I would call an extremely mature

auction business, like a Christie’s or Sotheby’s, looking at categories like handbags is interesting if you want to do a little bit of repositioning in people’s minds as to where these great, ancient auction houses are in the world. But I remain a little bit skeptical about the real growth opportunities there. It’s a challenge for our competitors now, because you can get lost chasing things with huge amounts of marketing, money, management time, etcetera, that actually don’t move the bottom line

very much.

|

You mentioned that the watches helped you expand into Asia. How did you think

about China before you could see all of this happen?

My first visit to [oversee auctions in] Hong Kong was in 1999, really before the arrival of mainland Chinese buyers in the art market. But when mainland Chinese started enjoying a little bit of freedom and were able to partake in the sales in Hong Kong themselves, and move money out of China and spend it on the sort of things that we were selling, it became absolutely obvious that this part of the world was going to be a very

significant player in the global art market. The interest in contemporary art helped, because the appetite in Asia for contemporary art was absolutely huge.

Some collectors in Korea and Japan and Singapore who’d been in the market for some time were suddenly joined by a huge number of young, new buyers who were interested in international contemporary art, not just Chinese contemporary art. It looked like an absolute no-brainer to develop the business there, and it still is. Probably two

to three years ago, incredible stats were being produced by all the auction houses, saying that Asian buying was [something like] 30 percent of the lots, globally, that year. The decision that all the auction houses made to reposition and invest in their businesses in Hong Kong was absolutely the right one. We’ve just got to believe that the geopolitical situation at the moment is going to somehow right itself, and that Hong Kong will be back as that incredibly vibrant hub for the Asian art

market.

|

|

|

During your tenure, Phillips built a building in London, moved to a new

facility in New York, and built headquarters in Hong Kong. Can you explain the importance of real estate?

It was key for Phillips to be seen to have a very significant physical presence in the most important markets in the world. And that was certainly a vision shared by Leonid Friedland, the owner of Phillips. He had actually made the decision to invest in the Berkeley Square building just before I joined. But when I accompanied him around the building, I

realized he was pretty serious about what he was trying to do, because it is a truly magnificent facility. That did transform Phillips’ presence in London in front of our key client base.

Then we obviously had looked for the right premises for Phillips in the biggest market in the world: New York. Phillips had been downtown, but we did find that a lot of our Upper East Side clients [saw] that journey as quite a long way. So, it was obviously important that we move back to Midtown. When

the opportunity came up, we started negotiating with Harry Macklowe and ended up creating a really quite extraordinary auction space right in the heart of New York.

The Hong Kong space was also important to us because Phillips was very new to the market in Asia, so it was very important for us to have a real physical presence there that people had to walk past and see our brand. I think our positioning in West Kowloon, with such an important space opposite the M+ museum,

has been fantastic for positioning Phillips in the minds of art collectors out in Asia.

You eventually got lots on the scale of your competitors. Was that simply having the financing, or having built enough trust in the market?

We—and I am quite proud of this—did triple the auction sales from just up to $400 million in 2014 to $1.3 billion in 2021-22. So we tripled our sales at a time when, actually, the market was relatively stagnant.

2014 is now seen as a

high-water mark in the market. So for Phillips to triple its sales in a stagnant market by taking market share away from our main competitors was fabulous, and it’s exactly what we set out to do. We did it by employing great specialists who had relationships with some of the most important collectors and buyers in the world, who were able to give confidence to the Phillips process and our ability to sell high-value works of art. We followed that up with a whole series of really quite important

works of art that we sold.

I think my favorite moment was when we sold a 1932 Picasso in London in 2018 for $58 million. In that same sale, we had a Matisse bronze that we sold for over $20 million dollars, and that was really groundbreaking for Phillips. It established us firmly in the world that we wanted to be in, which is to be seen as serious players in the high-value 20th century and contemporary art market.

|

We’re already running long, so I’m going to leave it here. I’ll be back on

Friday.

M

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Finally, a media podcast about what’s actually happening in the media—not the oversanitized,

legal-and-standards-approved version you read online. Join Dylan Byers, Puck’s veteran media reporter, as he sits down with TV personalities, moguls, pundits, and industry executives for raw, honest, sometimes salacious conversations about the business of media and its biggest egos. New episodes publish every Tuesday and Friday.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|