Welcome back to Wall Power, my private email detailing the inner

workings of the art world. I’m Marion Maneker.

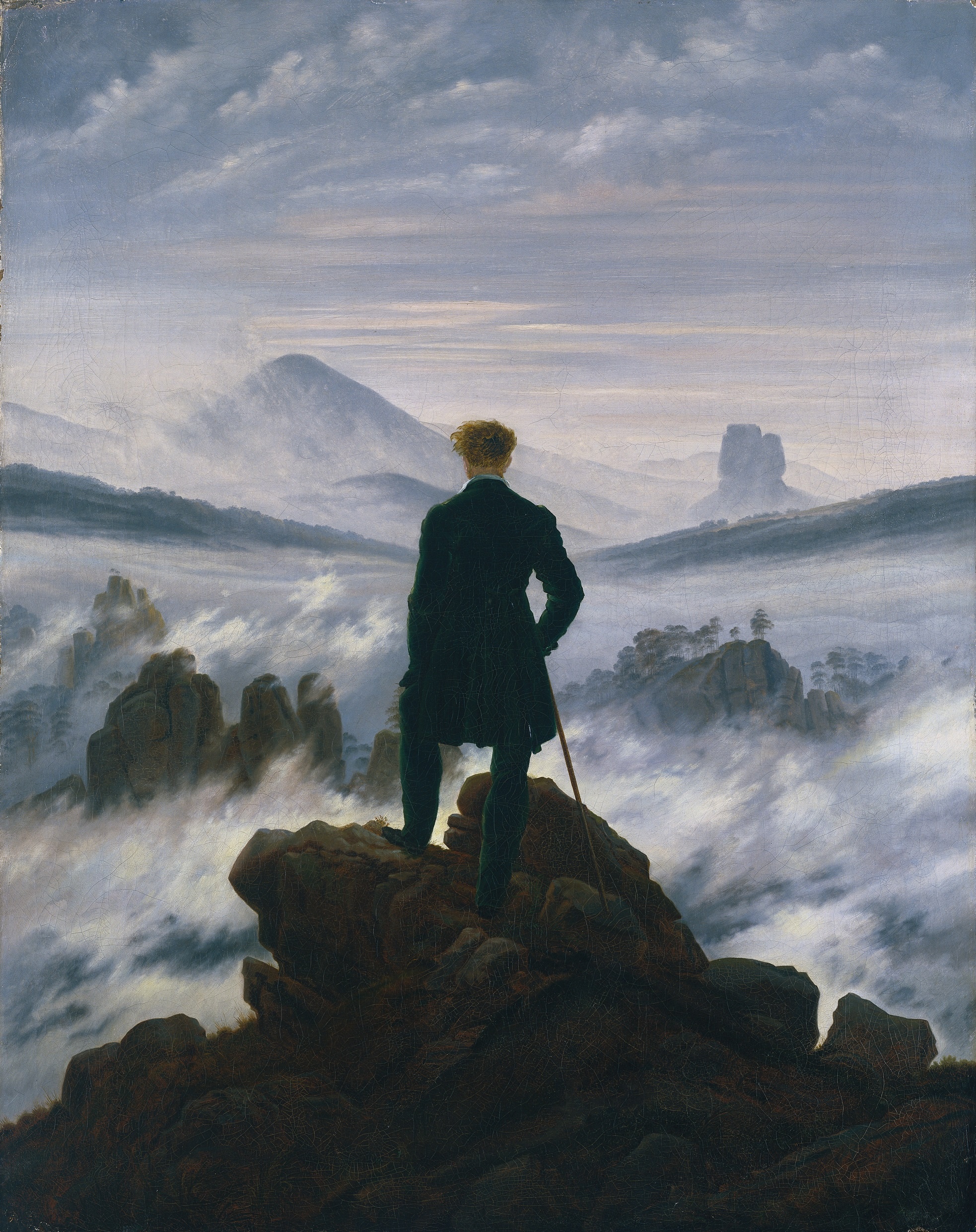

Tonight, my thoughts on the new Caspar David Friedrich retrospective opening at the Met this week. There are many ways to look at Friedrich—an important artist who is not well known in the United States, despite casting a long and complex shadow over both American art history and popular culture. You’ll know Friedrich

from the meme-able painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, but there’s a great deal more to think about given the nationalist political moment in which this show opens.

But first, Julie Davich has a few notes from around town…

|

|

|

|

Julie Brener Davich

|

|

- The

whimsical wares of Iris Apfel: “I didn’t give a damn about going to the party or being at the party,” Iris Apfel said in the 2014 documentary about her life. It was about “getting dressed for the party.” A fashion and interior design influencer before that was a thing, Apfel had an inimitable style defined by pattern, color, and most of all, whimsy. Oversize black glasses were her trademark up until her death, last spring, at age 102.

Those

glasses are not included in Christie’s online sale of the contents of her closet, open for bidding through Thursday, timed to Fashion Week in New York. But a similar pair that she designed for her Home Shopping Network line, Rara Avis, is. Rara Avis—“rare bird” in Latin—was also the name of Apfel’s

2005 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which launched her into the fashion stratosphere.

|

Unapologetically Iris: The Collection of Iris Apfel, Christie’s

New York. (Photo: Courtesy of Christie’s)

|

- Apfel and her husband, Carl, founded the textile firm Old World Weavers in 1950 and ran it together for more than four decades. They reproduced fabrics from the 17th-20th centuries and were also commissioned to do interior design projects, most notably for the White House under nine administrations. Their fabrics are featured in much of the clothing and upholstered seating on sale at Christie’s. The fashion was either custom-made or bought, often from

vintage stores, and most of it is around a size 4. The online auction also features purses, design accents, and costume jewelry, including hundreds of bangles—another Apfel signature. So far, the most desirable lot in the sale is a pair of circular brass pendant lights

with ceramic parrots, and the top fashion items are both Dior feathered coats, one multicolored and one brown.

It’s

a different, more accessible kind of sale for Christie’s. The combined estimate is only $150,000, with proceeds benefiting charitable causes. But celebrity sales can have that unknown zhuzh factor that can send prices soaring well above estimate. The Apfels traveled the world for their textile company, and the global influences can be seen throughout the collection. Her sense of style—and humor—come through most notably in her juxtapositions. “She made friends out of things not meant to

go together,” Liz Wight Seigel, Christie’s head of private and iconic collections, told me. Case in point: The life-size wooden ostrich draped with a plush Kermit the Frog. Christie’s is selling the two items together, exactly as Apfel displayed them.

|

- Tavitian sale results: Among the many, many things happening in America right now that were not on my bingo card is a sale of decorative arts from a heretofore mostly unknown collector almost doubling its estimate. Sotheby’s sold 99 percent of the 523 lots offered across its two live auctions of the collection of Aso O. Tavitian, for a total of $13.4 million against an estimate of $7.3 million. The sale of the

contents of Tavitian’s Upper East Side town house on Friday had an average of six bidders per lot, and the sale of items from his Berkshires country house on Saturday had an average of five bidders per lot.

Among the top sellers was a Tabriz carpet in good condition and of

unusually large scale for $156,000. This was almost eight times its $20,000 estimate, even though bidding was limited to American buyers because of export limitations due to its Iranian origin. The mahogany armchairs that I

highlighted last week—rare in their certain attribution to Thomas Chippendale’s workshop—doubled their estimate to make $240,000. An intricately carved mahogany

stand of Chippendale quality, possibly the only surviving stand with four legs instead of the usual three, sold for $276,000, almost seven times its estimate of $20,000—though still far less than the $440,000 that Tavitian paid for it at Christie’s London in 2006.

Two lots of

Huanghuali (Chinese rosewood) furniture also achieved notable prices—a pair of horseshoe-back armchairs sold for $228,000 against an estimate of $80,000, and a

leg table fetched $240,000 against an estimate of $100,000. Both pieces are iconic forms in a highly desirable material for collectors of Chinese works of art. Tavitian purchased both items at Christie’s New York: the chairs in 2005 for just $84,000, and the table in 2003, from the

collection of Gangolf Geis, for just $57,000.

- An artistic collab made on Instagram: What do Hilary Pecis and Rashid Johnson have in common? Both of their works have appeared on boxes of chocolates by andSons, the Los Angeles–based chocolatier known for aligning with artists to highlight the artisanal nature of its products. Some of the proceeds from previous collaborations have

gone toward the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, but the current Pecis collaboration for Valentine’s Day supports the LA Arts Community Fire Relief Fund.

The collaboration, like so many great marriages, was born out of a comment that Pecis made on one of the chocolatier’s Instagram posts. The boxes feature cropped versions of Pecis’s 2020 painting

Flowers, depicting a vase of pink and red flowers in her signature flat, decorative, colorful style. The 36-piece box, which sells for $125, is sold out online but is still available at the andSons store in Beverly Hills; the $85 24-piece box is available online and in-store.

|

|

|

Now, let’s tackle Romanticism and our time…

|

|

|

The Met’s new show of echt German romanticist Caspar David Friedrich, whom

Hitler co-opted for fascist appeal, raises some interesting questions about our cultural moment. Is Friedrich, the progenitor of a style now more familiar in comic books than art history books, worth taking seriously?

|

|

|

Why is the Met’s new show, Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of

Nature—a detailed retrospective of an artist that most Americans are only familiar with due to a popular meme—getting so much attention? I thought about this question last week as I stood on the steps of the Met early one morning, in a freezing drizzle, listening to a clutch of German art dignitaries chatter away brightly as we waited for the doors to open. There are probably two answers.

First, with 88 paintings and drawings, the Met’s current show of

Friedrich’s work—its third in 35 years—will be the largest, and “very first major retrospective in the United States of Germany’s most beloved painter,” as the Met’s director, Max Hollein, described it. The show features works on loan from three German museums—including the main draw, Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, the familiar image of a windswept early 19th century figure perched on a rocky outcropping, surveying a vista filled with scuds of fog that could

easily be mistaken for a tempestuous sea. The show is certainly an event worthy of the 250th anniversary of the artist’s birth last year.

|

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of

Fog (ca. 1817)

|

A quarter-millennium in, Friedrich is also having a moment in meme

culture. “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog has begun to turn up in American popular imagery in ways that are highly specific to our national dialogue,” the Met’s Alison Hokanson, one of the show’s curators, wrote in her excellent catalog essay tracing the serpentine and complicated legacy of Friedrich in the United States. “Reworked in explicitly political contexts, the picture’s various appropriations run the gamut from assertions of white nationalism to

the promotion of liberal environmental and economic programs.”

Indeed, though relatively few of Friedrich’s works are present in the U.S., American museums own all five of the Wanderer paintings—which the Met has gathered together for the first time. During the preview, heavily attended by museum professionals, I could see that the show was institutionally driven: Representatives of the German and

American museums seemed quite chuffed to see their hard work come together. I also got a sense I can’t fully explain that this kind of show would be quite popular with a segment of the donor class. Art, like politics, has a small but vital constituency that often determines what takes place more than the public, itself.

That said, this is

not a case of elite mandarins mounting a show of little interest to the plebs. Friedrich’s contemplative wanderer atop his rocky promontory has been grafted into numerous alternative contexts, from futuristic panoramas to apocalyptic hellscapes to riffs on everything from Star Wars to manga. There’s clearly something about German romanticism that resonates two centuries later. Like the romantics, we live in an era of overwhelming technological and political upheaval, and often want to

believe that there is something more that animates our spirits. And, just as in Friedrich’s day, there are overtly political purposes to this distraction from our rational abilities.

|

Friedrich was born in the Baltic seaport of Greifswald, which is now in

Germany but was then part of Sweden. (At the time, the Baltic was effectively a Swedish lake.) Raised a strict Lutheran, he migrated to Copenhagen to begin a classical artist’s training in drawing body parts from plaster casts before graduating to drawing figures from life. In Copenhagen, Friedrich seems to have developed a love of drawing landscapes, sketching outside instead of in a studio. But he also dropped out of his studies halfway through and moved to Dresden, the far side of

not-yet-unified Germany, which was then a cosmopolitan center of commerce and art near the border of what’s now the Czech Republic.

There, Friedrich found a synthesis of his own religious ideas, a growing German nationalism under Napoleonic French occupation, and a stripped-down aesthetic of landscape imagery. He first worked all this out in sparse drawings and etchings often overlaid with a sepia

wash that gives them a haunting quality. Those works on paper gave Friedrich his first critical success, which allowed him to launch himself as a painter.

And that’s where the Met’s show begins to take off. You can chart the ideas that culminate in the Wanderer, the apotheosis of German romanticism, or you can simply indulge in the moody, luminous imagery of cloud studies, seascapes, and reflective depictions of the rückenfigur, a figure seen

from behind who beckons the viewer to contemplate the image before both.

|

Caspar David Friedrich, Woman before the Rising or Setting

Sun (ca. 1818)

|

There’s no denying that Friedrich is an artist whose work is pleasing to

behold and straightforward in its emotional pull. (Though you will benefit from reading the excellent catalogue if you really want to understand the formal innovations that he employed and how those intersect with Napoleonic-era political and religious ideas.) But, yes, 200 years on, the images can seem tritely familiar from popular culture imagery, comic book dramatic effects, or even less subtle art. Indeed, given the way Friedrich’s innovations resonate through kitsch, it’s a surprise that

the Met hasn’t leaned further in that direction as a way to make the show more obviously relevant.

I get that such an approach would trivialize Friedrich’s importance as an artist. And I should acknowledge that there’s a very good catalogue essay on the Wanderer in popular culture. But I also know that there’s something on the other side of the intellectual and cultural spectrum that isn’t being addressed here. Elements of Friedrich’s

visual innovations were meant to express his own historically and religiously specific longing to exalt individual experience over cold rationalism, and also a desire to evoke a nationalistic identity—themes that later became central to German fascism, and which endeared him to Hitler—who, you may recall, originally aspired to be an artist before becoming a genocidal totalitarian. We, too, are living through a nationalist moment, and one where the exaltation of the irrational in the name of

individual empowerment and redemption has become a daily occurrence. Friedrich isn’t responsible for this, but it is spooky that we should have a detailed and extensive show of his work open just as the most negative aspects of romanticism are playing out in our own politics.

Here it is important to note, as the exhibition does so very well, that Friedrich’s own fame and importance was brief. Friedrich painted the first Wanderer in 1817, it is believed,

but by 1825 he had been denied the chair of landscape painting at the Dresden academy—a sinecure he would have coveted. His style would subsequently be eclipsed by that of the Dusseldorf Academy, which had a more direct influence on American landscape painting later in the century. Much of Friedrich’s work, which is now displayed in Germany or Russia, was forgotten and had to be rediscovered at various times, for purposes it’s doubtful that Friedrich would have supported. All of which is to say

that the appeal of this kind of romanticism is recurring, but not long-lived. Or, maybe I should say, let’s hope it’s not long-lived this time.

|

That’s all for today. Before I sign off, however, I wanted to acknowledge all

the readers who wrote in about Zona Maco, the Old Master sales, Miyoko Ito, and even someone who took issue with my closing observation that slashing government spending would depress G.D.P., and also, potentially, the art market. “[Elon Musk’s] goal is to cut inefficient spending, not reduce G.D.P.-generating expenses,” this person wrote. “In theory it could help increase G.D.P. if the government maintains stable spending by being more efficient. So this could

actually be good for the art world…” I had to explain to this person that there is no distinction between good spending and bad spending in regards to calculating G.D.P. So cutting $2 trillion in “wasteful spending” would still cause the economy to significantly contract.

For the record, I would love to see the budget, and its deficit, reduced substantially. But that has to be done legally and

responsibly, not as a $2 trillion shock. (Which is one reason, among others, these current efforts are not likely to be successful. Let’s hope.) That said, I did want to remind you all that I love hearing from you. I’m always happy to concede my ignorance and mistakes. If you want to tell me I’m wrong, or if there’s anything you think I missed, simply reply to this email. I’ll write you back. Or use +1.917.825.1391 to reach me on SMS, WhatsApp, or Signal.

Tomorrow, we’re gathering again in the Inner Circle, where we get wonky and examine some of the industry’s finer points. If you want to join us there, you’ll need to upgrade your subscription to the next level.

I hope you’ll join us there.

M

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and

insight to explain the backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|