|

Good afternoon, I’m William D. Cohan.

Hello and welcome back to Dry Powder.

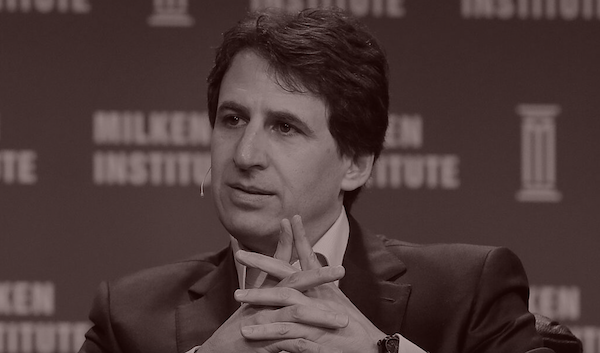

Today, I’m looking at the unlikely rise of Marc Rowan, the successor C.E.O. at the private equity giant Apollo Capital Management, after the fall of Leon Black. As readers of Dry Powder are surely aware, the leadership calculus at Apollo began to change dramatically during the pandemic, having nearly everything to do with Black’s long-running association with Jeffrey Epstein. But the full story of Rowan’s takeover was anything but textbook, even if it all may turn out just fine.

As always, you can read my reporting online, or in this email, below.

Thanks, Bill

Apollo Global Management has long been identified with its co-founder Leon Black. Now his successor Marc Rowan is on a mission to change that narrative—pronto—and to make a killing in the process. The gargantuan private-equity business is undergoing a massive generational shift these days, with a whole new cadre of leaders taking control of, cumulatively, more than $1 trillion in dry powder. At Blackstone, the emperor of the industry with some $730 billion of assets under management, co-founder Steve Schwarzman (age 74, net worth these days: $41 billion) has designated Jon Gray, 51, as his successor, even as he remains understandably reluctant to relinquish center stage. At KKR, co-founders Henry Kravis and George Roberts, both 77, have turned over the reins of the firm, founded in 1976, to Scott Nuttall and Joe Bae. At the Carlyle Group, co-founders David Rubenstein, William Conway, and Dan D’Aniello have moved on and out in favor of Kewsong Lee. (Lee’s co-C.E.O., Glenn Youngkin, gave up the role in part to run for governor of Virginia, a race he won on Tuesday.) In May, the co-founders of TPG handed over the sole C.E.O. role to Jon Winkelreid. (TPG is an investor in Puck.)

Then, of course, there is the succession drama that played out earlier this year at Apollo Global Management. This was succession of a different sort—more Succession than succession—driven by crisis, rather than by careful planning. While all the details remain publicly scarce, you can rest assured that the process by which Marc Rowan took over from Leon Black at Apollo was hardly textbook, even though it all may work out just fine. (Apollo’s stock is up more than 60 percent since Rowan succeeded Black in March.)

I had lunch with Rowan in September. We dined on salads, using plastic silverware, at Apollo’s new cafeteria in its Manhattan headquarters at 9 West 57th Street. He was eager to show it to me. I’ve known Rowan for 30 years, from back in the days when Apollo was just starting out and I was a young Wall Street investment banker covering the burgeoning private-equity industry. Our latest conversation was off-the-record, so I can’t report about it. But I can tell you that I’ve never seen him happier, more energetic, and more inspired by the responsibility he has been given to lead Apollo at this critical juncture. It’s almost as if he’s been waiting to come out from under Black’s shadow, or yoke, for decades. It’s fascinating to watch, to be honest. I, for one, didn’t think Rowan had it in him to be an enthusiastic leader of one of the most important bellwethers of finance.

Apollo, as you readers know, is the alternative-assets behemoth founded 31 years ago by Black, the former head of M&A at Drexel Burnham Lambert (the defunct investment bank) and, among others, two of his protégés, Josh Harris and Rowan. The firm, with $481 billion of assets under management and a market value of $30 billion, has long been identified, even more than most other private-equity firms and their founders, with Black, who is 70 and more than a decade older than both Harris and Rowan. Channeling Black, Apollo has always been known as a firm that has been willing to take risks that other firms have not been willing to take, such as buying the debt of bankrupt or failing companies and then converting that debt to equity to get control. It is equally well-known for its relentless financial creativity. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, for instance, Rowan and Apollo started an insurance company—Athene—from scratch, took it public in 2016, and then Apollo just recently agreed to buy it back, making another fortune.

All this financial engineering made Black very rich—his net worth is estimated at around $10 billion—with all the usual accoutrements of the very wealthy: a Manhattan townhouse (it used to be the Knoedler art gallery), a home in Beverly Hills (that used to belong to Tom Cruise), and a palatial mansion in Southampton. In 2012, he bought Edvard Munch’s pastel, The Scream, for nearly $120 million. Until recently, he was chairman of the board of trustees at the Museum of Modern Art. Such was Black’s pervasiveness at Apollo that until he was tapped in March to succeed him, Rowan had opted for semi-retirement rather than get all bollixed up in the question of whether he or Harris, or someone else, would be Black’s successor.

The leadership calculus at Apollo began to change dramatically during the pandemic, having nearly everything to do with Black’s long-running association with Jeffrey Epstein, the infamous pedophile who supposedly committed suicide in his Manhattan jail cell in August 2019. The rough outlines of the Black-Epstein plot that lawyers have allowed to be made public are well known by now. Black and Epstein had known each other since at least the 1990s. In 1997, Black named Epstein one of the original trustees of Black’s family foundation. In 2020, following Epstein’s death, Black revealed in a letter to investors that Epstein provided him with “estate planning, tax and philanthropic advice.” In October 2020, Black, who remains Apollo’s largest individual shareholder, asked the independent directors of the Apollo board to conduct an investigation into his relationship with Epstein. The independent directors hired Dechert, the law firm, to conduct the investigation and, in January, produced a minimalist report that revealed that Black had paid Epstein $158 million, between 2012 and 2017, for his tax-structuring and estate-planning advice. The Dechert report left many unanswered questions and, of course, there was no one willing to answer them, in the great corporate tradition. (In June, Black was accused of sexual abuse. Black has adamantly denied the accusations and sued both his accuser and her law firm.)

Most people I know on Wall Street found the Dechert report to be a bit of a joke. But, of course, we’ll never know what really happened between them, unless Black wants to give me a call. (That’s not likely to happen.) In the meantime, Black was going to stick around as Apollo C.E.O. until June. But the timeline got speeded up to March, with Rowan agreeing to come out of his lair to lead the firm, winning a power struggle of sorts with Harris, who had previously made a bold, and ultimately unsuccessful, power grab to take over the firm. If the details of what really happened between Black, Harris and Rowan ever gets shared, they would make one helluva HBO or Showtime mini-series, a cross between Billions and Succession, with a twist of the Sopranos. (Black is hardly alone in losing his job as a result of his association with Epstein; on Tuesday, Jes Staley stepped down as C.E.O. of Barclays, after just shy of six years, because of the circumstances surrounding his relationship with Epstein.)

With the stock price soaring and Black out of the picture, Rowan appears to be in his element and hitting his stride. One of his first moves as C.E.O., in March, was to have Apollo buy the 65 percent of Athene that it didn’t already own, for $11 billion. On October 19, he led a multi-hour “Investor Day” for Wall Street research analysts that was most notable for the fact that not once did anyone mention the name Leon Black, an omission that would have been previously unthinkable. Rowan talked about the importance of “culture” to him and to Apollo, a vein of thinking that one rarely associated with Black’s Apollo, which has always been known to be more than a little cutthroat. “If I had to choose between strategy and culture, I take culture every day all the time and twice on Sunday,” Rowan said.

He continued: “It is ultimately the most important thing. If we get culture right, we win. We can always adjust the strategy. I want to assure you, we are getting culture right. We have always been known as an idiosyncratic investor, as a contrarian, as an entrepreneurial firm at scale. What you haven’t known as much, because it’s too easy to gloss over, is the people side of the business.”

Indeed, Rowan made clear repeatedly in his hour-long presentation that he would not be dwelling on the past. “Nostalgia is a very dangerous point of view in our business,” he said, “because, in the next five years, it’s going to change more than it has in the past 10. We should embrace that. We shouldn’t be scared by that. This is just an amazing time for our business.”

Rowan also spent plenty of time at the Investor Day talking about how Apollo would be becoming even bigger and more important. He said Apollo was a “high-growth business” that would be doubling its assets under management in five years, to nearly $1 trillion. The acquisition of Athene—Rowan’s baby—is a “growth accelerant” for Apollo, he said, in much the same way, I presume, that Warren Buffett’s acquisition of the insurance company Berkshire Hathaway, back in the day, changed the trajectory of his career and made him one of the wealthiest men in the world.

He said Apollo remained committed to private equity, even though he described it as “not a growth business.” It is raising a new fund that is expected to exceed the $25 billion fund it raised in 2018. “It’s a farming business,” he said, of private equity. “You plant, you harvest, you plant, you harvest.” Apollo also remains committed to alternative credit, such as buying distressed debt, and to loaning money at high rates to companies that can’t get it anywhere else. He repeatedly compared Apollo to the way GE Capital used to finance companies, making boatloads of money along the way. (At our lunch, we talked about GE’s implosion, the focus of my forthcoming book, and he seemed well aware of the role GE Capital played in bringing GE to its knees; it’s doubtful Rowan will make that same mistake at Apollo. But I won’t say any more than that.)

Apollo is also committed to providing “private credit,” money that is lent to companies that Apollo keeps on its balance sheet, to capture the spread—the difference between Apollo’s cost of capital and the interest it receives on the loans—for itself. One example of “private credit,” Apollo-style, is the 2019 $1.7 billion loan Apollo made to Gannett, the newspaper company, at a hefty 11 percent interest rate.

At the Investor Day, one of Rowan’s partners described Apollo’s opportunities in “private credit” as going from the size of “a pond” to the size of “an ocean.” He doesn’t want to accumulate more assets just to accumulate more assets. He wants to make sure he can reward with high returns the investors who trust Apollo with their money. “We are in the business of providing excess return per unit of risk,” Rowan said. “It’s no more complicated than that. If we forget that, though, and we seek to just take in A.U.M. without regard to our ability to put that money to work, returns will commoditize and ultimately fees in our business will commoditize.”

In short, Rowan seemed almost giddy with Apollo’s prospects, now that Black is out of the picture. Critics such as Senator Elizabeth Warren—who allege private-equity has run roughshod over the economy, leveraging up businesses, reaping huge financial rewards for themselves and their limited partners while often leaving employees and creditors holding the bag—will be disappointed by Rowan’s optimism.

He makes it sounds like there’s very little that will be stopping the Apollo juggernaut. “I’m fortunate to lead a business that gets better every day, literally better every day—demographics, income, wealth transfer, indexification and evolving regulation,” he said. “I was preparing for this [talk], and I was thinking, which of these is the most powerful driver? I’m not sure I could say. We have so many powerful trends driving our business that we expect not only growth in the business, but you can see what’s been projected in the alternatives universe more generally. This has been a really good business for 20 years, and I see no signs of this letting up or changing. I think the forces that are driving this are just too powerful right now.”

Of course, by the Investor Day, Rowan must have known that Apollo had had a blowout third quarter, the results of which he announced on November 2. The firm made $725 million in what it calls “distributable earnings”—profits that can be returned to shareholders—nearly four times the $205 million Apollo made in the third quarter of 2020. “Our business is thriving,” Rowan said in announcing the third-quarter results, “and we are accelerating on all fronts.”

As a journalist, one is tempted to dismiss Rowan’s unbridled enthusiasm for Apollo’s business prospects as just so much corporate pabulum. But with the economy still recovering from the pandemic with seeming robustness, and the Federal Reserve remaining intent on keeping the cost of Apollo’s fuel close to zero, it’s hard to see (at least from a near-term macroeconomic perspective) what might curtail the party for Apollo, and the rest of the industry, in general. Rowan’s optimism seems well justified, when you cut through it all.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t potential pitfalls for Rowan, et al. The multiples of EBITDA paid by private equity buyers—with dry powder up the wazoo—have averaged an eye-popping 12x, driven by the white-hot debt markets, where nearly everything seems to fly off the shelves these days. The Fed keeps threatening to “taper”—and did so again today—which, if it happens, could finally lead to higher interest rates and a tamping down of the party. And, of course, debt investors could start demanding greater compensation for the risks they are taking, which could also chill the debt markets.

But, as I’ve said, I’ve known Rowan a long time. This guy is as smart and as sharp as it gets. I’ve also long known Bill Lewis, the respected banker who joined Apollo last month as a senior partner. He wouldn’t risk his Wall Street career and reputation by going to Apollo at this moment unless something different and special is going on. This could get interesting.

FOUR STORIES WE’RE TALKING ABOUT The indie film industry is notorious inside Hollywood for penny-pinching financiers, lax on-set managers, cheap hires and poor on-sent conditions. MATT BELLONI The merger appears reckless, even to those in Trumpworld. As one former senior advisor put it: “It’s got as much gas as the Hindenburg.” TINA NGUYEN A candid conversation with Eric Schmidt about A.I., his relationship with Biden, and how “woke-ism” has changed the C-suite. TEDDY SCHLEIFER The formative years of David Zaslav’s career explain as much about the history of cable as they portend about the future of streaming. WILLIAM D. COHAN

|

-

Join Puck

Directly Supporting Authors

A new economic model in which writers are also partners in the business.

Personalized Subscriptions

Customize your settings to receive the newsletters you want from the authors you follow.

Stay in the Know

Connect directly with Puck talent through email and exclusive events.