Welcome back to Wall Power. I’m Marion Maneker.

Tonight, I’m taking a closer look at Christie’s recently announced Riggio auction, which will take place in May. The market has been waiting for a collection like this to hit the block for some time, in order to recalibrate. And while we’ll be seeing only a fraction of Len and Louise Riggio’s holdings, the seven works that have thus far been revealed (out of the 30

that will be on offer) deliver plenty of data to help us gauge the market as it moves forward. Also, if you pay attention to the provenance, you’ll see why Pace partnered with Sotheby’s to make a rival bid. More on all that below.

But first…

|

- A dispatch from Dallas: If you want to spend some quality time with leading figures in the art industry, upgrade your account to access Wall Power’s Inner Circle private email. Tomorrow, we’ll be talking to Guillaume Cerutti, Christie’s chairman of the board, about his recently concluded eight-year tenure as C.E.O. If you haven’t signed up yet, here’s a taste of last week’s conversation with Dallas collector Howard Rachofsky, founder of the local nonprofit and exhibition space The Warehouse, and his new partner Thomas Hartland-Mackie.

Marion Maneker: How do you partner on individual works of art—such as the large Cecily Brown

triptych you bought together and donated to the Dallas Museum of Art, or the Howardena Pindell triptych you own together that’s in the current show?

Howard Rachofsky: Over two decades, we’ve been collecting with the notion that a good part of the collection, if not the whole, will go to the public domain in general, and the Dallas Museum in particular. With the Cecily Brown show up at the Dallas Museum and traveling to the Barnes, the work was both good visibility and an

important landmark for the artist. It also lets the world know that the Dallas Museum is a serious, serious player in the universe of contemporary art.

Thomas Hartland-Mackie: When Howard and I were acquiring that work together, we didn’t know what exactly we were going to do in the future, but we recognized the significance of it. As Howard said, a work of that significance, you’ve really got to think about where it ends up, and so [the DMA] felt like a perfect home.

In

terms of the other works that we’ve collected together, I think it initially started because we found installation-based or very large-scale works that we both really loved but had nowhere to store or display. So it felt like quite a radical decision to acquire some of these things alone. Either Howard found them and I was excited to be a part of it, or I found some and Howard was excited to be a part. This started many years before the idea of collaborating on The Warehouse, and so that was

what kicked all of this off.

Thomas, I’d love to hear about your age cohort and their level of interest in engaging in collecting. You are 37. It’s a very interesting art community in Dallas—and there’s been a big influx of people to Dallas over the past four or five years.

Hartland-Mackie: I spend a lot of time in London. There’s probably a bigger collector base among my generation in London, but there’s a great young collector base in Dallas, and it’s

growing. Because Dallas doesn’t have a huge gallery scene, it means that places like The Warehouse, and obviously institutions like the DMA and the Nasher, etcetera, are even more important to open people’s eyes to the art world. I think Two x Two [the Rachofskys’ annual art fundraiser benefiting amfAR and the Dallas Museum of Art] was incredible for that. It was a way for young collectors who had the means to collect, but maybe didn’t have the experience yet, to dip their toes into buying great

works of art that had obviously been well curated, with a feeling that your money was going to this great cause.

Several friends of mine who started collecting have felt the same way. Some of their initial purchases have been through Two x Two. Then they start to get more interested and learn more. Then they go visit galleries when they’re traveling.

|

Now, let’s get to the main event…

|

|

|

This May, Christie’s will auction the $250 million collection of Len Riggio,

the late founder of the bookstore chain Barnes & Noble. The first seven pieces revealed from the collection—which is filled with historical work—offer clues about the estimates and what the sale could mean for the broader market.

|

|

|

At this stage in the art market cycle—after all the emerging talent fads and

the downturn—we should probably be witnessing a new level of interest in high-quality historical work. And now Christie’s, which won the competition to auction some of Barnes & Noble founder Len Riggio’s art collection, will have a chance to test this proposition. More specifically, the auction house will attempt to sell the late entrepreneur’s $250 million collection of 30 works in their own dedicated evening sale in May.

The works chosen for auction reflect a level of market confidence, and they look like they were selected to raise the greatest amount of money while removing the fewest artworks from the collection. (The estate has to pay taxes, and this is probably the most convenient way to raise the money. Which would you rather sell right now: your investments or your art?) Christie’s hasn’t commented on whether the collection is directly guaranteed, but the estate may

have chosen to receive a larger portion of the total price paid in lieu of a guarantee. It’s also a bit early in the process for Christie’s to have put estimates on the works. (They may also be out there gathering third-party guarantees before they publish the estimates closer to the sale…) Nevertheless, I’m going to give you my best educated guesses.

Christie’s is touring seven of the 30 works on

offer, all made in the 20th century and generally not the kind of art that most people associate with Riggio, who sat on the board of the Dia Art Foundation. They include two paintings by René Magritte and two sculptures by Alberto Giacometti, as well as paintings by Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, and Piet Mondrian. From the photograph of the Riggios’ Manhattan apartment in the promotional

materials, we know the sale will include a Balthus painting from 1944-45, about which Christie’s isn’t providing information just yet.

The rest of the works are being kept under wraps until closer to the sale, but the selection suggests the Riggio estate is being strategic and market-minded. After all, the seven announced lots (and even the Balthus) respond to demand recently seen in the auction market.

|

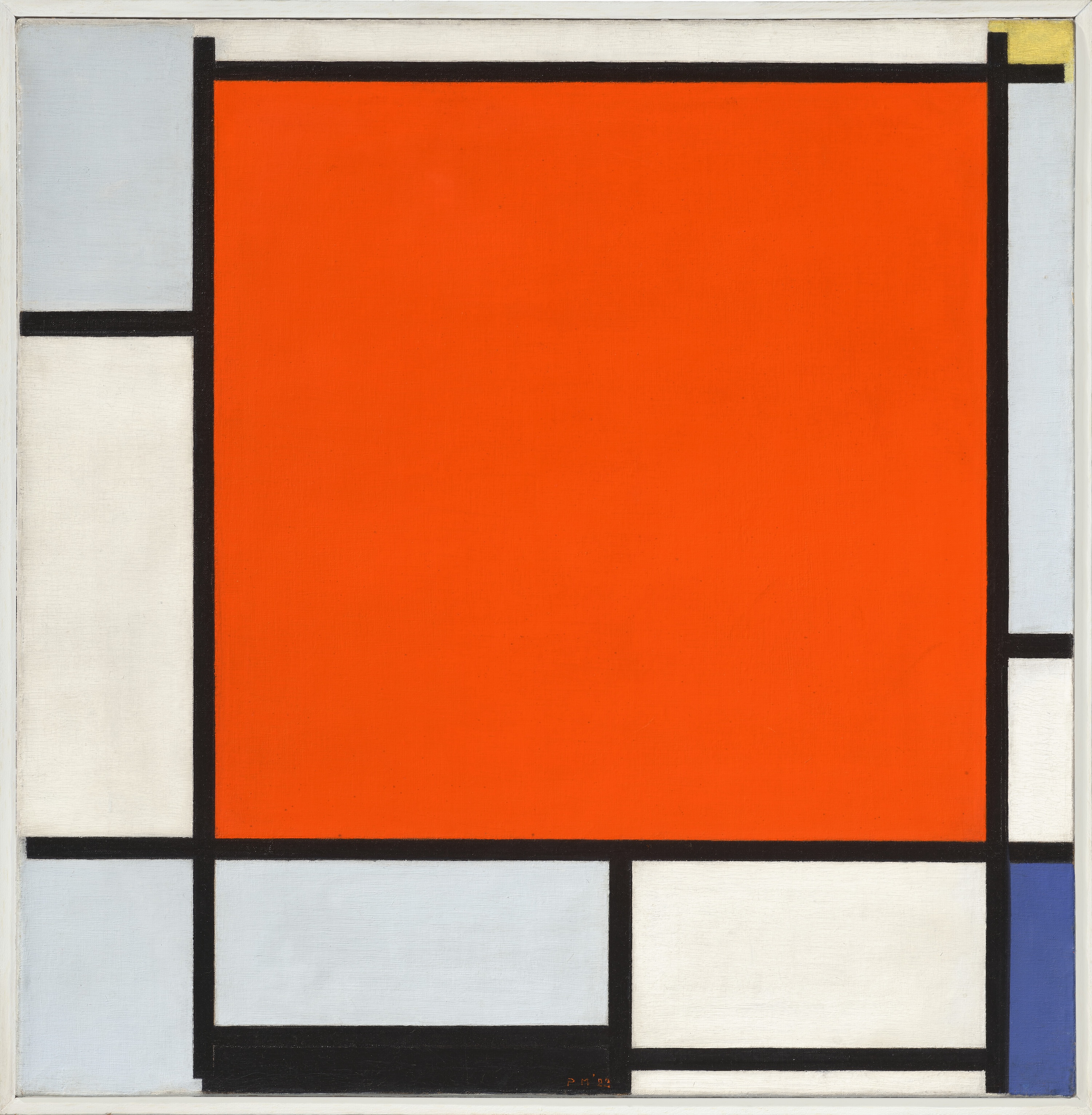

Composition with Large Red Plane, Bluish Gray, Yellow, Black and Blue, from

1922, will be the third square Mondrian with a dominant red rectangle to come to market in the past decade. Only 21 inches, this work is actually slightly larger than the two later works (from 1929 and 1930) that sold prior. And its provenance is likely to attract buyers: It was originally bought by Antony Kok, a close friend of artist, before coming to the United States with Nelly van Doesburg, who sold it to Henri-Georges Doll, an executive at

Schlumberger and husband to heiress Anne Schlumberger, whose sister was the collector Dominique de Menil. Doll owned the painting for 40 years—far longer than his marriage to Schlumberger.

|

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Large Red Plane, Bluish Gray, Yellow, Black and

Blue (1922).

|

The Riggios bought their painting 25 years ago. In 2015, the 1929 work sold at

auction for just above $50 million to the bond fund manager and museum patron Jeffrey Gundlach. Six years later, a rectangular work from 1927 with a red section sold for $26 million. Then, in November of 2022, Composition II, a 1930 work that is very similar in appearance to the Riggios’ painting, sold for $51 million.

With that in mind, Christie’s is likely to estimate the work

close to the record price. They’ll be setting a bar, and we’ll be watching to see whether that rarefied world of a few dozen collectors thinks it’s a reasonable price—or even cheap. Adding to the appeal of the Riggios’ Mondrian is the fact that the painting seems to be in very good condition—often an issue for Mondrian’s work a century after he made it.

Close behind the Mondrian is one of the Magrittes that the Riggios acquired only in 2023. A small version of

L’empire des lumières, from 1949, this painting had been sold in 2017 for $20.5 million. It returned to auction amid the run-up in Magritte prices, and contributed to steep acceleration in prices for this particular series when the Riggios bought it for nearly $35 million.

|

René Magritte, L’empire des lumières (1949).

|

Normally, selling a recently purchased painting so quickly would be difficult.

But, as everyone knows, the top price for a Magritte rose from $79 million in 2022 to $121 million in 2024—and both of those sales were for works from the L’empire des lumières series. A gouache from the series set a huge new record late last year at nearly $19 million. Does that mean this painting will sell for 50 percent more than it did in 2023? In any case, the estimate was $25 million when the Riggios bought it. Maybe this time it will carry a slightly higher one—$30 million or

even $35 million.

The other Magritte, Les droits de l’homme, from 1947-48, also has an interesting provenance—and, with the recent show celebrating the 100th anniversary of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto held at the Centre Pompidou, there are now likely more potential buyers for this work than ever. This Magritte passed through dealer Alexander Iolas and, twice, Pace Gallery. It was owned for a decade by

television game show producer and noted collector Mark Goodson. The painting is large: nearly 5 feet tall and 4 feet wide.

|

René Magritte, Les droits de l’homme (1947-48).

|

There are few comparable auction sales for the work; its size makes it a standout. Smaller works

featuring a similar image but lacking this one’s flaming musical instrument have sold for $3 million and $2.4 million. And a tiny painting of the flaming brass instrument, itself, sold for $3.5 million in 2021. That might offer a clue about where this work will ultimately be estimated. Combining the two images with its size should get the estimate closer to $15 million or $20 million, given the stamina of the Magritte market.

|

Relief for the Picasso Drought

|

Longtime readers will remember that the Picasso auction market basically shut

down last year, with a mere $167 million in sales, after averaging around $508 million each of the three previous years. This isn’t the first time that the Picasso market has gone dormant. According to ARTDAI’s numbers, there were similar volume drops in 2016, 2019, and 2020. Still, the demand for Picasso doesn’t seem to be flagging—it’s most likely a supply issue. Help may be on the way, starting with one

of the seven paintings that Picasso made of Lee Miller, the model and war photographer, and the subject of a 2023 film starring Kate Winslet. Miller was a friend of Picasso, dating back to the 1930s through her own collaborations with Man Ray.

Femme à la coiffe d’Arlésienne sur fond vert (Lee Miller), from 1937, follows two other versions

that were sold at Christie’s in recent years: In 2022, L’Arlésienne (Lee Miller) sold for $13 million. In 2023, a more complex version painted 10 days later made almost twice that: $24.5 million. The one from the Riggio collection, made a day after the $13 million painting, is slightly more complex than the first work, but not quite as developed as the later one. It is likely to be estimated at $15 million or $20 million.

Another work in the Riggio collection that was previously owned by Iolas is Andy Warhol’s blue The Last Supper, made in 1986. The Riggios bought the painting at auction in 2010 for $6.8 million. Similar 40-by-40-inch Last Suppers, with two stacked reproductions of Leonardo’s famous fresco, have sold for much higher prices. The magenta version, for instance, sold for nearly $19 million in 2017. A yellow one

sold for $8.2 million in 2018. Last year, a pink-and-red camouflage version sold for $6 million. Good marketing suggests the Warhol will carry an estimate closer to that last sale, with the potential for bidders to push it higher.

The final two works announced for the sale are Giacometti sculptures cast in 1958. One is the 41-inch version of the artist’s famous Femme de Venise I conceived in 1956.

There are six casts in the edition. This one passed through the prestigious hands of Aimé Maeght, Claude Bernard, Pace Gallery, and Jeffrey Loria. Another sold at auction in 2007 for $8 million—the same sale at which a different Giacometti work set a then-record price of $18 million.

Since that time, Giacometti prices have exploded, with the record

set at $141 million in 2015. The next highest price for a Giacometti at auction was the $78 million that cryptocurrency billionaire Justin Sun paid for Harry and Linda Macklowe’s Le Nez, which has since been sold to David Geffen. (Sun recently sued Geffen, claiming the work was sold by his art advisor without his consent.) A cast of Femme de Venise III sold at Christie’s two years ago for $25 million.

Considering all that, the likely estimate for this work is probably a conservative $15 million.

The other Giacometti, while also cast in 1958, was conceived in 1927. Le Couple is only 23 inches tall and was owned by the Museum of Modern Art for more than 25 years, before it was sold to Pace Gallery, who then sold it to the Riggios. In 2019, another cast was auctioned for $2.5 million. I’d expect Christie’s to estimate this one at $2-3 million.

|

Following my recent observation that the Times hadn’t given

Mel Bochner an obituary, a gallerist wrote in to express that it seemed like I was taking a swipe at the late Walter Robinson, who got the royal treatment from the paper. This person took exception to my description of Robinson’s Artnet magazine as sparsely trafficked, and went on to assert that it was “a go-to source for art

reviews among people who care(d) about those sorts of things. And the NYT does plenty of obits for less ‘prominent individuals.’”

Fair enough. I meant no disrespect to Robinson or his memory. But Artnet’s audience under Robinson was a fraction of its current footprint. (By the way, the big showdown over Artnet’s leadership takes place on Thursday. More on that in a subsequent newsletter.)

Anyway, the Times rectified the Bochner situation late last week with an obituary written by Penelope Green that gives the artist credit for mounting one of the first conceptual art shows while teaching at SVA in the 1960s. As Green explained, Bochner believed conceptual work had to take some material form. Eventually, for

Bochner, that material form would be language.

Anyway, I’m glad the Times got it together. The news organization can be a bit of a bully in demanding to receive first crack at all major art-related announcements. That’s fine. It has a big audience. But if its editors are going to seek to dominate a category, they also have a responsibility to cover all aspects of that world in a timely and

authoritative way, which includes having obituaries of important artists pre-written. Just saying…

More tomorrow for the Inner Circle subscribers. See you then,

M

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and

insight to explain the backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|