Hello and welcome back to The Best & The Brightest. I’m Leigh Ann

Caldwell on St. Patrick’s Day, during a much-needed recess week on Capitol Hill after the brutal, 10-week Senate session. I know, I know: I’m not sympathetic to lawmakers whining about being in Washington—it’s their job, after all—but 10 consecutive weeks is a long time to be in session. Staffers, for their part, are definitely happy to have a breather from their bosses. On that note, if you’re a staffer with some extra time this week, send me an email.

Coffee’s on me.

In tonight’s issue, some news and notes from me up top, before my partner Abby Livingston digs into the great tactical debate now engulfing congressional Democrats in the wake of last week’s funding vote.

But first…

|

- Chuck’s

book: As I predicted, Chuck Schumer had to cancel his book tour this week because of security concerns. Given the left’s anger at Schumer for voting in favor of the Republican funding bill—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez characterized the vote as turning “the federal government into a slush fund for Donald Trump and Elon Musk”—and the increasingly in-your-face tactics of some activists, the timing of Schumer’s book

tour for Antisemitism in America: A Warning couldn’t have been worse.

Indeed, Schumer’s funding (non)fight has angered the base so much that they don’t want to hear from him on any topic. After I filed my latest dispatch on Schumer yesterday, I listened to him being interviewed by Lulu Garcia-Navarro on a New York Times

podcast in which he explained his strategy for dealing with Trump. His plan, he said, was to pound him with arguments on topics like potential cuts to Medicaid, hoping to make him so unpopular that Republicans will no longer be beholden to him.

Schumer told Navarro that the last time Trump was president, Democrats found leverage with Republican colleagues

and voters when Trump’s poll numbers fell below 40 percent. “We’re going to keep at it, keep at it, keep at it, until he goes below 40,” Schumer said. (The latest polling shows Trump around 47 to 48 percent approval.) Will Democrats, particularly the left wing of the party, be that patient?

- Democrats’ deportation quandary: Despite their growing investment in the idea that the judiciary can provide a necessary and effective bulwark against

Trump’s unchecked (by Congress) agenda, Democrats have been largely silent about the president’s apparent decision to ignore U.S. District Judge James Boasberg’s order to halt the deportation of alleged members of a Venezuelan gang to El Salvador. Politically, of course, Democrats don’t want to be seen as standing up for violent criminals’ ability to stay in the United States, but Trump’s refusal to abide by a federal court order is, theoretically, one of Democrats’ foremost

concerns. (The White House has claimed it did not defy the judge’s order, since the deportees were already outside of U.S. territory when it was issued.)

The White House, meanwhile, is doubling down on what it seems to view as a political masterstroke, releasing a slickly-produced video of the deportations, showing detainees being led out of planes by the neck and zooming in on their faces as agents shave off all their hair. Press secretary Karoline Leavitt retweeted the

video, saying, “The American people voted for this,” adding that the administration looks forward to the case reaching the Supreme Court.

|

|

|

The current animosity rippling through the party isn’t along the familiar personal or

ideological lines, but over a tactical dispute on how to fight Republicans. The first signs of a revolt are already manifesting on the campaign trail.

|

|

|

The anger coursing through the Democratic Party, following Chuck Schumer’s tactical

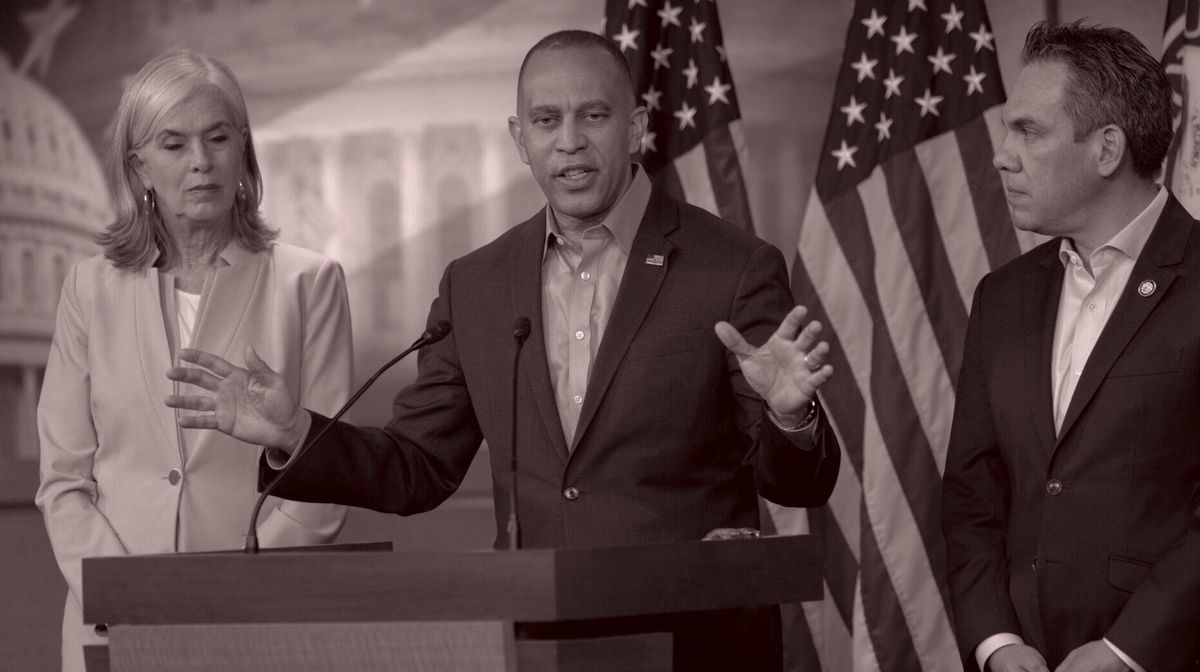

surrender to Republicans on last week’s government funding bill, isn’t limited to furious Squad members, Bluesky luminaries, and activist group leaders. Sure, Schumer has his defenders, especially among Democrats who are well versed in procedure and the boomeranging consequences of shutdowns. But elsewhere across Capitol Hill, longtime donors are turning on traditional allies. Some staffers, I’m hearing, are unusually at odds with many of their bosses. Even House minority leader Hakeem

Jeffries refused to defend his Senate counterpart. Voters are lighting up Capitol Hill switchboards, wondering why Schumer didn’t use the filibuster, and why Democrats won’t fight.

What’s remarkable about this latest episode, though, is not just the intensity of the intraparty fight. It’s the division over tactics, rather than tribes (Hillary vs. Obama, Bernie vs. everybody) or policy (does one support or oppose

Medicare for All?). Sure, Democrats seemingly all agree that something must be done to oppose Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s efforts to dismantle the federal government, and push back against their disregard for congressional authority—but a party that has long prided itself on “governing” is now at a crossroads, and debating whether to channel its inner Tea Party and adopt “obstruction” instead. “What’s always held the party together since 2017 is

stop this guy, and there’s no way to stop him anymore,” said Tom Bowen, a Democratic consultant. “It’s unadulterated rage, because there’s nothing we can do. We’ve been primed for eight years to stop this guy, and we didn’t, and it just sucks.”

The funding fight crystallized the divide. House Democrats, led by Jeffries, argued that the party should not condone a partisan Republican funding bill that included cuts to healthcare, veterans’ benefits, and nutritional

assistance, and did not put any kind of leash on Musk. Instead, they argued, the party should have held strong, with Senate Democrats demanding concessions in exchange for ending a filibuster. Schumer, however, was never temperamentally inclined to kick sand in the gears. He countered that a shutdown would only play further into the hands of Trump and Musk, disrupt the livelihoods of more federal workers, and ultimately hurt incumbents at the ballot box.

He might be right, but recent

polls of party members—taken before the funding bill passed the Senate—show the Jeffries school ascendant, at least for now. As my partner Leigh Ann Caldwell noted over the weekend, nearly two-thirds of Democrats in a recent

NBC poll said they’d prefer that House Democrats stick to their positions than compromise with Trump to pass legislation. CNN found 57 percent of Democrats saying the party

should work to “stop the Republican agenda” rather than “work with Republicans.”

Adopting those tactics would shift Democrats into a very different—and for some, more uncomfortable—mode. In the recent past, Democrats found leverage in the minority by working with their Republican counterparts to outflank the far right. During the party’s other wilderness periods over the past 15 years, they could count on divisions among House Republicans to ensure their own votes would be

necessary, giving them leverage in negotiations. Occasional shutdown aside, this insulated the Senate from fielding purely partisan Republican spending bills.

That all changed last week, when Mike Johnson, with Trump as his whip, consolidated the entire House G.O.P. conference (sans Thomas Massie) behind a spending bill for the first time in recent memory. In keeping their micro-majority together, Republicans completely reset the calculus of power on

Capitol Hill, bypassing the Democratic minority entirely in the House and then steamrolling them in the Senate. To hear certain Democrats tell it now, Schumer’s capitulation robbed the party of its best point of leverage against Trump and Musk.

|

Democrats I spoke to this week worry that the political friction will manifest on the campaign trail, too.

Ever since Citizens United allowed for unlimited corporate campaign spending, Democratic party leaders—including Schumer and Nancy Pelosi—optimized their campaign funding strategy to maximize efficiency. They created a system in which outside groups, campaign committees, and candidates worked together to secure the cheapest television rates possible for the

fall campaigns and to avoid any overlap in spending on the same races. This involved near constant communication within the party’s political class: members, donors, committee staffers, super PACs, and consultants, albeit within a complicated legal framework.

Alas, that delicate balance falls apart if its various actors lose trust in (or motivation to help) one another. There are calls that might not get made or returned. Hands that aren’t shaken at receptions. Member leadership PAC

checks to colleagues’ campaigns somehow get lost in the mail. Conversations aren’t had, and political intelligence isn’t shared.

And then, of course, there’s the ultimate expression of infighting: primaries. Democrats have long held the belief that primaries drain money, talent, and energy away from general election campaigning—that is, from beating Republicans. Unlike today’s Republican party, wherein Trump (and now Musk) wield primaries as a routine threat, Democrat-on-Democrat violence

is historically rare. It is difficult to defeat a House Democratic incumbent (A.O.C.’s victory over Joe Crowley notwithstanding), and nearly impossible to bring down a Senate Democratic incumbent (the late Arlen Specter was the last one…). Particularly in competitive seats and districts, party leaders have

worked together to keep candidates they believe will lose a seat out of the race.

Yet the current flare of anger directed at Schumer, paired with the party’s emergent generational warfare, might be creating a new permission structure for insurgent Democrats. Indeed, the norms against challenging incumbents

have been slipping for a while. Back in late 2012, Cory Booker enraged many New Jersey Democratic elders when he announced his campaign for a Senate seat already held by Frank Lautenberg, who had yet to announce whether he would run for reelection. Lautenberg died a few weeks later, but Booker had committed a severe breach in

protocol and was the subject of sore feelings for months among those who believed he had unnecessarily forced the issue on an old man. Katie Porter’s similar move was less incendiary in early 2023, when the California congresswoman announced her run for Senator Dianne Feinstein’s seat, even though California’s then-89-year-old senator had yet to announce her own plans. Patience with Feinstein was already running out, but even then, Porter’s move

was still considered a little gauche.

That’s all changed. Perhaps the hottest campaign gossip in Dem circles is the future of Dick Durbin’s Senate seat in Illinois. Durbin, 80, hasn’t announced whether he will retire at the end of this term, but there’s a frenzy of activity below the surface, as generations of up-and-coming Illinois Democrats have coveted this seat. I’m told that such Dems are “all banging at his door”: making calls, hiring staff that

appear geared toward Senate campaigns, and engaging in fundraising disproportionate to their current offices. Now, none of this maneuvering is raising a single eyebrow. Meanwhile, the primary threats are flying elsewhere, most notably in the movement to draft A.O.C. to challenge Schumer in 2028. Schumer is a D.S.C.C. chairman at heart, which means his instincts are about protecting his incumbents. And it’s likely not a coincidence that Durbin was the only in-cycle senator to vote to advance the

bill on the floor.

Bowen, the consultant, sees value in competitive primaries. “Brush fires like this allow something else to grow,” he said. “The party doesn’t have the identity it needs to win yet. This is where it comes from. It comes from the primary fights.”

|

Dems are taking further blows in their weakest hour—namely, the deaths of two members in the last two

weeks: Sylvester Turner, a 70-year-old freshman, and 77-year-old Raúl Grijalva, who was forced to relinquish his ranking membership on the Natural Resources Committee late last year. While both men are sincerely grieved by Democrats, the losses also eased the passage of the Republican spending bill through the House last week.

A much-respected former Democratic member told me that any member over 70 should see the writing on the wall. “People dying in

office, members losing their brainpower in office, being out of touch—A.I., crypto, social media, etcetera—out of it, not with it … It’s time to go,” this person said. This logic should apply to recruitment, too, the former member added, arguing that people over 60 shouldn’t run for Congress for the first time and the party should prioritize recruiting people in their thirties and forties. “By the time you get really good at this job, you need several terms,” this person explained. “It’s not an

ageist thing. … We need people with fight in them … who understand these times, especially with social media.”

At the same time, Democrats are fairly confident they’ll take back the House majority next term, and all those senior members will be on the cusp of getting back committee and subcommittee gavels. It’s an unvirtuous cycle that will simultaneously make it harder for them to retire and likely generate more primaries.

Still, I’ve detected some gallows

optimism in Democratic circles. Democrats, after all, have lived through a Trump administration before, and they know that the next Trump controversy could well have a uniting effect that will make their colleagues and constituents forget their current tensions. “We have to move on,” a former Democratic chief told me, hopefully.

|

|

|

Join Emmy Award-winning journalist Peter Hamby, along with the team of expert journalists at Puck, as they let you in on the

conversations insiders are having across the four corners of power in America: Wall Street, Washington, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood. Presented in partnership with Audacy, new episodes publish daily, Monday through Friday.

|

|

|

Unique and privileged insight into the private conversations taking place inside boardrooms and corner offices up and down

Wall Street, relayed by best-selling author, journalist, and former M&A senior banker William D. Cohan.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences,

click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|