Welcome back to Wall Power. I’m Marion Maneker.

Tonight, I’ll

go deep on an arcane photographic printing process that, in the words of Phillips’s worldwide head of photographs, Vanessa Hallett, helps to “reveal the beauty of everyday life.” Now nearly extinct, the dye transfer process was mastered by Guy Stricherz and Irene Malli, a married couple who began working in New York’s Little Italy more than 40 years ago, but ended up re-creating their darkroom—down to the placement of the light switches—on

Vashon Island in Washington state. “The more they practiced at it,” Hallett said of the process, the more “they were able to get the saturation of the colors more vivid and tones more heightened.” Details on that in a moment.

Julie Davich is heading to Maastricht next week for the first time. If you want her to swing by your booth, or if there’s anything you think she should see, hit her up at JDavich@puck.news. And if you see her wandering through the maze, please introduce yourself.

But first, here’s Julie on a major ceramicist whose work is building momentum…

|

|

|

|

Julie Brener Davich

|

|

One of the best New York exhibitions that you may have missed last summer was the retrospective

of Hawaii-born postwar ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City. We’ve talked before in Wall Power about the market resurgence for Takaezu’s ceramics—an uptick due partly to her grandniece’s decision to create the Toshiko Takaezu Foundation in 2015, four years after her death at age 88. As often happens, more museum interest prompts more market interest, and vice versa. And the big market-making moment for Takaezu came in April 2023,

when a single-artist sale of 62 works at Rago Auctions made $1.7 million, including an auction record of $541,800, against an estimate of $20,000, for the artist’s celestial purple Moon. You can see the retrospective at its current tour stop in Houston or at yet another show of Takaezu’s work in Columbus, both of which opened last week.

Takaezu was part of a movement in the 1950s that elevated clay from its utilitarian purpose to an art form. Her experiments in form were

an evolution in simplification, from multi-spouted pots to “tamarinds” (shaped like seedpods) and ultimately to the closed form. Her glazes, meanwhile, became more layered over the course of her career, drawing comparisons to her color field and abstract expressionist contemporaries. It is these later “paintings in the round,” as her decorated closed forms are called, that command the highest prices.

|

Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo: Courtesy

of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

|

The touring retrospective features examples from her entire body of ceramic work, as well as

some paintings and weavings. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston has replicated many details of the Noguchi exhibition, which was awe-inspiring not just for the works, but also for the way they were displayed, like the planetary orbs nestled in glittery black sand, as if amid the cosmos. Concurrently, the Columbus Museum of Art opened Wild Earth: JB Blunk and Toshiko Takaezu, the first museum pairing of the artist with another giant in the movement. Blunk worked

primarily in wood and ceramics, and, like Takaezu, apprenticed in Japan and was primarily interested in organic forms.

The Houston exhibition closes in May, then tours to Wisconsin and Hawaii. The Columbus show is on view through August. If that’s not enough Takaezu for you, James Cohan Gallery is opening an exhibition of her rare monumental bronze sculptures at its Tribeca space on May 16.

|

|

|

Now let’s geek out on dye transfer printing…

|

|

|

An auction at Phillips offers a rare collection of William Eggleston prints,

made with an arcane and all-but-extinct process to amp up the vividness of everyday life.

|

|

|

Guy Stricherz and Irene Malli are retiring. They’ve had a

great run. In 1981, Guy started the Color Vision Imaging Laboratory, in what we now call Nolita, but which was then just Little Italy, to make dye transfer prints of color photographs. An offshoot of the Technicolor film process that revolutionized the movie industry, dye transfer printing was invented in 1946; the process dominated the advertising industry and graphic arts for nearly half a century, until 1994, when Kodak discontinued making the materials for the process and sold its remaining

stock of film, paper, and dyes to master printers like Stricherz.

For the past 30 years, Stricherz has been making color dye transfer prints along with Malli, who, after graduating from Cooper Union, answered an ad for a job at the studio that Stricherz ran with another partner. She eventually married the master printer—and became one herself. They’ve done this for many photographers, but none more than William Eggleston, of whose work they have made editions of some 250

images in dye transfer. “Every print is kind of like a puzzle,” Malli said. “You have to figure out how to get from what you want to the final print.” Regarding what makes the process so special, Stricherz has said: “The dyes commingle and sort of dance to produce a bond that gives the print an almost three-dimensional

look.”

The combination of Stricherz, Malli, and Eggleston has become a thing in its own right lately. David Zwirner gallery just closed a show in Los Angeles titled William Eggleston, The Last Dyes, featuring some of Eggleston’s images using the very last of the Kodak dye transfer materials—some stockpiled by the Stricherzes, some from Eggleston’s own dwindled supply. This week, Phillips opens an exhibition of 43 lots of Eggleston’s work, signed by the photographer, for an

auction on March 18. These dye transfer prints are Stricherz and Malli’s own printer’s proofs—the apex of the artist’s intent in the hierarchy of fidelity and expression, and the reference point by which all other examples can be measured.

|

William Eggleston, Untitled (Peaches!) (1973).

|

Making dye transfer prints is a persnickety process that’s precise in the way it generates

color; it requires both the experience of a master and the approval of the artist. When working with Eggleston, the Stricherzes would create as many prints in the numbered edition as commissioned, along with a set number of artist’s proofs. They would also, by predetermined agreement, make a single printer’s proof that Eggleston would sign. Because of the process’s precision, and since the dyes do not fade in the way other printing processes do, these dye transfer prints are the perfected master

prints of Eggleston’s work. Or, as Phillips head of photography Vanessa Hallett said: “You can’t have a better print than their printer’s proof.”

|

Among the lots in the auction is a rare

portfolio of 75 dye transfer prints titled Los Alamos, which captures the best of Eggleston’s images from 1965-74. Los Alamos was made in an edition of seven, Hallett told me, and of those seven, two are in museums (MoMA and Museum Ludwig in Germany), three are owned by well-known collectors with commitments to institutions, and one set was broken up.

(Translation: It’s unlikely that you’ll ever get another chance to buy one.)

If that were not enough to emphasize its rarity, the portfolio is being sold as a single lot with two other portfolios of 13 photographs each, Cousins and Lost and Found, that come from negatives that Eggleston thought were lost at the time he created Los Alamos. Together, the entire lot contains 101 of Eggleston’s most famous and consequential images printed by dye transfer, and it’s

what the photographer wanted to be seen as a single body of work. Its $2 million estimate would be a record for Eggleston’s work at auction. Los Alamos (just the 75 prints) hit a then-record of just over $1 million at auction in October 2008, a terrible time for the art market; that record lasted 16 years until last November, when an oversize print (not a dye transfer) nearly 5 feet tall, of a cocktail on a plane, sold at auction for the current record of $1.4 million.

|

William Eggleston, Memphis (Tricycle) (1969).

|

In addition, the sale contains the largest dye transfer prints of Eggleston’s seven most famous

images, what he calls his “magnificent seven.” If you follow contemporary art at all, you’ll likely recognize Untitled (Peaches!), Memphis (Tricycle), or Greenwood, Mississippi (Red Ceiling) immediately. These examples are still not very large, at 17 by 26 inches. (Eggleston had much larger prints of these images made in 2012—5 feet tall or wide, depending on the orientation of the photograph—but those are made with the pigment print process on board, instead

of photographic paper.)

Mysteriously, though, this is the first time anyone outside the Eggleston orbit has seen prints in this size of the images. The cataloging says the works are from an edition of 10, plus three lettered artist’s proofs printed in 2015. Not only have these prints never been auctioned before—but until the Stricherzes decided to sell some of their printer’s proofs, Hallett had not known of their existence.

|

Phillips has an interesting position in the photography market. “The majority of collectors I

work with,” Hallett said, “are contemporary collectors who incorporate photographs into their collection.” Like Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, and Bernd and Hilla Becher, Eggleston appeals to collectors who view his work as a new way of seeing, one that just happens to use the medium of photography.

His reputation as a photographer and artist is also bound up with the impact and acceptance of color photography as a

medium. In 1976, MoMA gave Eggleston a watershed show that changed the way the medium was viewed by artists, photographers, and collectors. After the MoMA show, photographers shed their reliance on using moody black-and-white printing to achieve the seriousness of high art. After all, MoMA had validated color.

Eggleston’s discovery of the dye transfer printing process in 1972 was integral to his success. Stricherz and Malli did not become Eggleston’s go-to dye transfer printers until

later, but once the trio met, their work became intertwined, because the married duo could realize the photographer’s vision in ways that other printers could not.

After all, in color photography, making an image is really only half of the process. The rest is all about making the print. “It’s well enough to make an excellent transparency in the studio or out in the field,” Stricherz said in a video made for the Zwirner exhibition. “But you want a print, and that is the thing.” Artists don’t exhibit transparencies, which we used to call slides; a carousel slide projector is an awkward way to view an artist’s work. “You need a physical object,” Stricherz said.

And it’s a lost art. The dye transfer process was already fading in commercial relevance when Stricherz first got involved in the early 1980s. “It’s kind of nice to be in a medium that is really—it’s not

practiced anymore,” Stricherz said. “There’s something about it being so rarefied … to do something that nobody else is doing.” Now, with the last of the Kodak materials used up, and the knowledge that Stricherz and Malli acquired over decades all but useless, it’s pretty much gone.

The secret of the dye transfer process was in the color separation. Though it frustrated many others,

Stricherz had the control to make it extremely flexible, and produce a strikingly different print from one hour to the next. Imagine the joy that Eggleston must have felt to work alongside him tweaking the colors, tones, and highlights. “You can radically change the print,” Stricherz said. “What you’re trying to do is make a print that looks as close to that transparency as can be done. And that’s really what William Eggleston wants. He wants a faithful reproduction of the transparency at full

frame.”

|

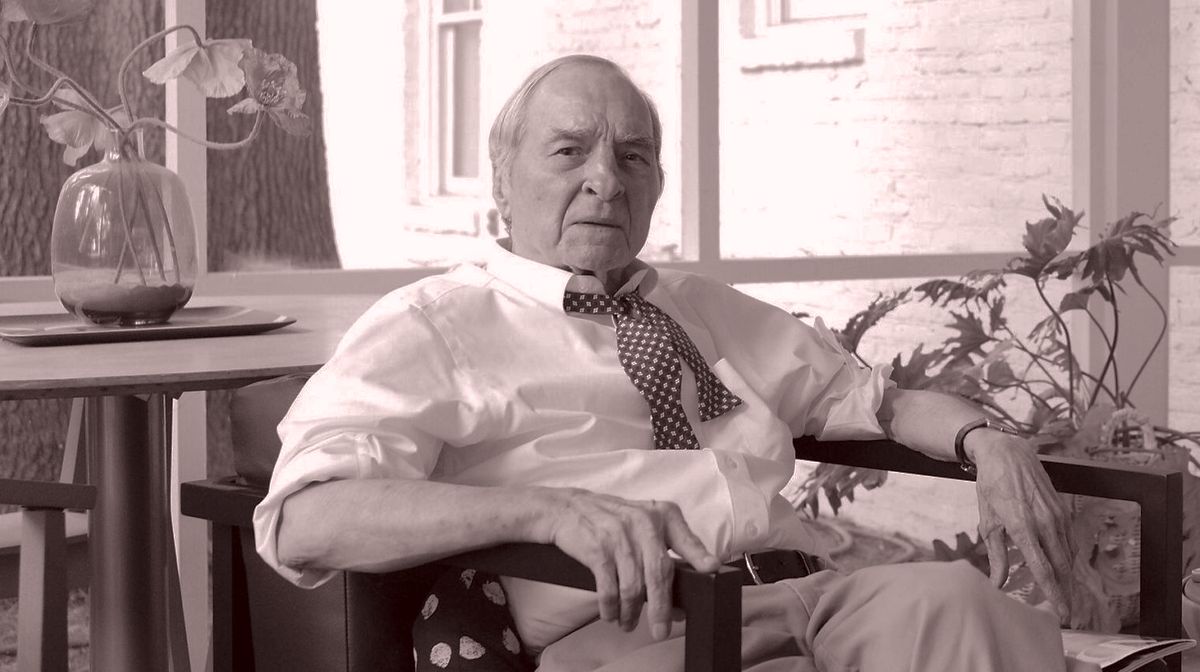

The European Fine Art Fair opens at the end of the week in Maastricht. The Financial

Times has a full package of stories, including a second look at the massive 2,600-piece collection of Chinese export porcelains amassed by 97-year-old architect Renato de Albuquerque and now housed in a private museum in Sintra, Portugal. There’s also an interesting look at museum donors, under the guise of the increased due diligence that museums

have to conduct on donors, after the Sackler family debacle. But that’s another story.

The FT points out that new donors have emerged, including hedgie Yan Huo, who’s now on the board of the Met, but so far has donated only $10 million. (By the way, the story all but gives up any hope that rich donors to the arts will emerge from the tech

world.) There’s also a great biography of Hilla Rebay, the first director of what is now the Guggenheim Museum. And African modernism gets a spotlight, both from a gallery that will be showing at TEFAF, but also at some important

museum shows opening at the Centre Pompidou next week and at the Tate Modern in October.

|

Hope this all was helpful. We’ll see you again tomorrow for the Inner

Circle.

M

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and

insight to explain the backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY

10006

|

|

|

|

_01JP3A4H9AZK0Q0YTX9F12N3XG.jpg)