Welcome back to Wall Power. I’m Marion Maneker, winging my way back to New

York from Los Angeles, but thinking about Hong Kong, where we saw some interesting sales.

Tonight, I’m going to write about the Jack Whitten show that just opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Julie Davich has a report on the Beatriz Milhazes show at the Guggenheim. And I’ll give you a quick tour of the highlights of Swann’s African American art sale later this week.

I’ll have an even more detailed look at the Hong Kong

data for all you market nerds—especially the ones who want to know whether we’re moving in the right direction or still losing traction—in Wednesday’s Inner Circle edition. If you’re not yet a member and you want to geek out, upgrade your subscription here. Obviously you can afford it. But can you afford to live without it?

Up first, a couple notes on the $150 million modern

and contemporary art sales in Hong Kong…

|

- Christie’s

20th/21st century sales total $100.4 million: Top lots in the evening sale were Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Sabado por la noche (Saturday Night), which made HK$112 million ($14.5 million); two works by René Magritte, Rêverie de Monsieur James at HK$47.5 million ($6.1 million) and La Clairvoyance at HK$28.8 million ($3.7 million); Zao Wou-Ki’s 28.8.67 at HK$48.8 million ($6.3 million); Yayoi

Kusama’s Pumpkin, which sold for HK$39 million ($5 million); and Auguste Renoir’s La Promenade au bord de la mer, which achieved HK$34.9 million ($4.5 million). Day sale winners were works by Yoshitomo Nara, Kusama, Alex Katz, and Christine Ay Tjoe on the 21st century side; and Zao, Chu Teh-Chun, Sanyu, and Claude Lalanne in the 20th

century sale.

- Sotheby’s modern & contemporary sale totals $47 million: Marc Chagall’s painting made HK$34 million ($4.37 million); a Renoir nude sold for HK$23.5 million ($3.02 million); and a sculpture by Henry Moore made HK$20.5 million ($2.64 million). Top lots in the day sale included Tetsuya Ishida, whose work sold for HK$3.8 million ($490,000); Auguste Renoir at the same price; Fernando

Zóbel, whose painting made HK$3.1 million ($400,000); and Camille Claudel and Kazuo Shiraga at HK$3.04 million ($390,000).

- Phillips’ New Now sale totals $2.8 million: Finally, Phillips’ sale saw top lots from Ayako Rokkaku, Charlotte Perriand, Li Hei Di, Issy Wood, and George Condo.

- And now, for a quickie preview of the Swann African American sale…: April 3 is the date of Swann Galleries’ African American art sale, Nigel Freeman’s category-defining semiannual event. This season, the top two lots are estimated at a healthy $200,000, for Norman

Lewis’s untitled abstract painting, from 1954, owned by his partner Joan Murray; and for John Biggers’s late

painting Death and Resurrection from 1996. Hughie Lee-Smith’s haunting 1959 painting

Girl Fleeing is estimated at $150,000.

That’s the same estimate that’s been placed on Romare Bearden’s collage The Green Room, and Ed Clark’s untitled abstract

painting, both from 1971. Other noteworthy works with very low estimates include Howardena Pindell’s Untitled #81, from 1976, a mixed media

work estimated at $50,000 mostly due to its small size; and Suzanne Jackson’s Side-a-Sapelo, from 1999, also estimated at $50,000—it’s only the second of her

abstract works to come to auction, but expectations have risen since the first one was sold in 2020.

These works are hardly the only ones worth paying attention to in the sale. At a time when prices for works on the primary market often begin in the mid-five figures, there are numerous strong works

by important talents in the Swann sale that are estimated at the lower end of that range. Don’t get too attached to anything you find there—you won’t be the only one paying close attention and thinking about bidding.

|

Now here’s Julie on the Guggenheim’s clever use of its own inventory…

|

|

|

|

Julie Brener Davich

|

|

Museum Hopping: Beatriz Milhazes at the Guggenheim

|

Installation view of Beatriz Milhazes: Rigor and Beauty, Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald/Courtesy of the Guggenheim Foundation

|

When Mariët Westermann took over as director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and

Foundation last year, she had a few priorities for the iconic New York institution, which has been struggling financially since Covid. First, she wanted to optimize the museum’s permanent holdings. She decided to install a rotating series of Collection in Focus exhibitions in the small tower galleries that angle off the main spiral rotunda. For the Guggenheim, this represented a savvy way to cut down on exhibition costs while also pulling out of storage works that otherwise would not be

seen.

The first Collection in Focus exhibition was a small Mondrian show curated by Westermann, a fellow Dutchperson, which will be up through April 20. The second show in the series, which opened a couple weeks ago and will be on view through September 7, is a selection of 15 works by Brazilian artist Beatriz Milhazes. Organized by Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães, the Guggenheim’s curator of modern and contemporary Latin American

Art, it marks the artist’s first museum show in New York.

Milhazes was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1960, and her paintings combine modernist geometric abstraction, à la Sonia Delaunay, with the sights and colors of Brazilian culture, like Carnival, Tropicália, and bossa nova. She’s been painting since the 1980s, but it was in the mid-1990s that she landed on her signature “monotransfer” process of painting motifs on plastic sheets, then applying the sheets to the

canvas, leaving behind the dried shapes.

Of the 15 Milhazes works in the Guggenheim presentation, there are five large paintings, dating from 1995-2000, that entered the museum’s collection in 2001 as part of the Bohen Foundation Gift. Gutiérrez-Guimarães opted not to exhibit the sixth work from that bequest—an oversize screen print—in favor of showing seven smaller paper collages from 2013-2021, from the artist’s personal collection, in order to demonstrate a wider range of her output. The artist also loaned a recent painting, The Golden Egg, which was in the 2024 Venice Biennale, and facilitated a loan from a Brazilian private collection of another work, O Caipira (The Caipira), from 2004, which fit perfectly on a narrow vertical wall in the gallery. The final monumental painting in the show, Mistura Sagrada from 2022, is courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery. (Translation: It is available for purchase.)

The next show

in the Collection in Focus series, which will run indefinitely, is Faith Ringgold, opening May 9.

|

|

|

Now let’s look at MoMA’s Jack Whitten show…

|

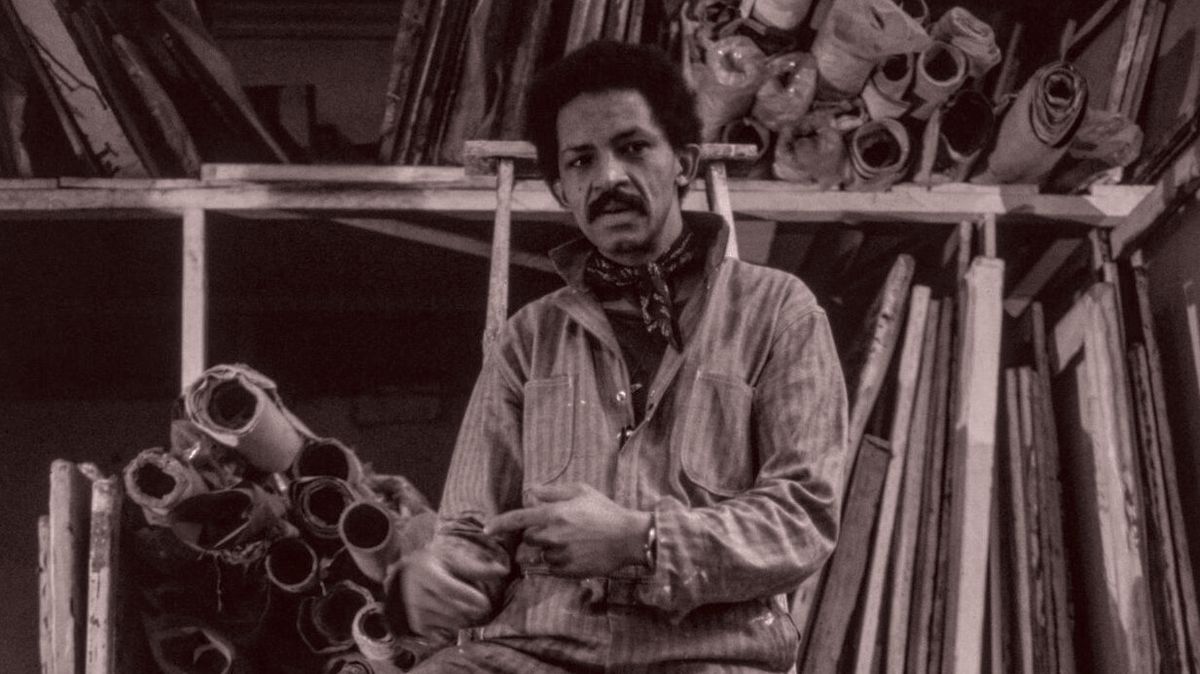

As the Trump administration attacks D.E.I., a slew of museum exhibits showcasing African

American art is culminating with major mid-career and historical retrospectives opening this spring. The Museum of Modern Art’s Jack Whitten survey is the surprise standout, and reveals deeper insights into the dilemmas of being a Black artist.

|

|

|

I went to see the Jack Whitten retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art out of a sense of

obligation. Of course, I had heard of Whitten as an influential and important African American artist, but he was not one that I knew much about. And the work I had seen, like the show at Hauser & Wirth last fall in London, highlighting his ’70s era black-and-white process paintings, was too subtle and subdued for me to be able to appreciate prima facie. I needed more context and background to understand what I was seeing.

As I rode the escalator to MoMA’s sixth floor galleries,

where Jack Whitten: The Messenger is on view, and heard the music of Art Blakey in the background—his band was The Jazz Messengers—I got that sinking feeling that the show was going to be everything I feared: high-minded, self-congratulatory, and boring. To make matters worse, the entrance to the show displayed more black-and-white works, different from the ones I had seen in London, suggesting the retrospective was going to be a dark and lugubrious exercise in nodding

dutifully at Whitten’s work.

It was only when I found myself making a third trip through the massive 175-work retrospective, to make sure I was seeing what I thought I had just seen, that I realized how absorbing and instructive the show really was. Like other artists of his era, Whitten had a brief breakthrough moment in the 1970s, including a solo show at the Whitney, only to have the art world move on quickly. Making less flamboyantly colorful work than his peer Sam

Gilliam—who also achieved a level of fame and acceptance in the ’60s and ’70s, only to also fade into obscurity before being “rediscovered”—Whitten was a cerebral painter, interested in materials and process. In many ways, it was easy to understand how he could have been forgotten. But the art in the MoMA show argues that Whitten was an innovator of enormous proportions.

|

The revelation of the MoMA show, at least for me, was that Whitten had a wide and varied practice.

But even more important, his pieces seem to have prefigured—or simply arrived at earlier—strategies for creating abstract work that we would later see in the art of many other more famous and familiar artists.

In 1970, having already created a platform in his studio that allowed him to work on canvases that lay horizontally on the floor, Whitten constructed a large tool to rake the layers of accumulated acrylic paint with a 12-foot wide edge. Whitten attached different surfaces to the

edge, eventually alighting on a squeegee-like tool that he called “the developer.” The resulting paintings look nothing like Gerhard Richter’s abstracts, and yet the technique was the same.

Michelle Kuo, the MoMA curator who organized the show, discovered Whitten’s work while serving as the editor of Artforum magazine. She likened Whitten’s discovery of this technique to the simultaneous but separate inventions of calculus by Gottfried

Wilhelm Leibniz and Isaac Newton in the late 17th century. “The developer” was only one of several wholly unexpected techniques that Whitten played with. Early on, he was given chemicals and equipment by Xerox Corporation so he could explore their artistic possibilities.

|

Installation view of Jack Whitten: The Messenger, The Museum of Modern Art, New

York. Photo: Jonathan Dorado/Courtesy of MoMA

|

Walking through the MoMA retrospective, one is confronted with a number of different works that seem both

excitingly new and uncannily familiar. His early colorful abstract paintings from the 1960s will recall the recent work of painters like Catherine Goodman and Julia Jo. In his later, mosaic-like paintings, I saw images that brought El Anatsui or Lucio Fontana to mind. The full breadth of his talent is undeniably on display. The show also features examples of his wooden sculptures, which owe a clear debt to Cycladic art and

African power figures, sprinkled throughout. Perhaps one reason that Whitten did not achieve a certain level of fame as an artist in his lifetime, beyond the limited opportunities to exhibit his work, was that he was simply too protean.

|

Installation view of Jack Whitten: The Messenger, The Museum of Modern Art, New

York. Photo: Jonathan Dorado/Courtesy of MoMA

|

As the show and catalog explain, Whitten was born in Bessemer, Alabama. His father, a coal miner, died when

he was 5 years old. Whitten’s exceptional talent and intelligence led him to Tuskegee, where he’d intended to become a doctor, and where he also learned to fly. Despite the opportunities for economic advancement there, Whitten’s encounter with artists as a student, and a bitter experience marching in the Civil Rights Movement, led him to New York to pursue a degree at Cooper Union, where he would later teach.

I could not help but think about Whitten in the context of the current political

and cultural moment. As we all know, the Trump administration is mounting a direct attack on “wokeism” and diversity, equity, and inclusion. The premise of Trump’s cultural attacks is that Black artists are worthy of attention only as special pleading. Whitten’s retrospective heightens our awareness of how we’ve deprived ourselves by having previously excluded so many great talents.

Indeed, it may be that we are seeing this retrospective only because of the concerted

effort by the museum community almost five years ago, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, to focus on Black artists. This month brings a handful more major museum shows featuring African American painters. Ironically, these shows only seem to feed the MAGA movement’s paranoia that there’s an overemphasis on identity art. Yet to walk through the MoMA show and marvel at Whitten’s polymath abilities, his deep political and social engagement, and his restless imagination is to be

reminded all over again of the loss to ourselves and our culture that we did not know and appreciate a talent like Whitten’s better when he was alive.

|

I’m going to leave it there this Sunday evening. Rest up, folks, we’ve got a big week ahead

of us.

M

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and insight to explain the

backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest players. Anchored by

preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|