Welcome back to Dry Powder. I’m Bill Cohan.

There are few investors more enigmatic and powerful than Masayoshi Son, the multibillionaire founder of SoftBank, who appears to be on the cusp of investing some $15 billion to $25 billion in Sam Altman’s OpenAI. In a recent conversation at the Economic Club of New York, former FT editor Lionel Barber—whose biography of Son,

Gambling Man, was published in October—offered a comprehensive review of Masa’s extraordinary career. In today’s issue, some choice anecdotes and observations from Barber’s talk.

But first…

|

- S.B.F.’s long putt: It appears that Sam Bankman-Fried, the incarcerated former crypto wunderkind, is trying to jump on the Trump pardon bandwagon. This has to be the longest of long shots for Sam, a onetime Democratic megadonor who was no fan of Trump back in the day (and vice versa). S.B.F. at one point even offered to pay Trump $5 billion not to run for president. Plus, S.B.F. has been waging a one-man legal war—see: his

recent, still-pending appeal of his conviction—against Sullivan & Cromwell, the white-shoe Wall Street law firm that once advised him and now represents his former company, FTX, in its bankruptcy proceedings. Trump, as it happens, has a new firm representing him in the appeal of his hush money conviction: Sullivan & Cromwell.

Nevertheless, according to

Bloomberg, S.B.F.’s parents—the former Stanford Law professors Joe Bankman and Barbara Fried—are trying to petition the Trump administration to spring Sam from Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center barely a year into his 25-year sentence. I reached

out both to Sam, in prison, and Joe Bankman, but didn’t hear back.

- Lina’s warning: It was hard not to feel a twinge of pathos, last week, reading Lina Khan’s exit interview with the Financial Times, pontificating about the growing dangers of private equity, just before Blackstone, the

leading alternative asset manager, announced blowout fourth-quarter earnings on Thursday. The juxtaposition was like something out of a Twilight Zone episode featuring parallel universes: In Khan’s world, the craven private equity monsters are taking over and destroying the world; for Blackstone, meanwhile, it’s all puppies frolicking through meadows of wildflowers.

In her FT interview, Khan warned of “catastrophic consequences” for the country if Trump and his

appointees allow private equity firms to continue buying up chunks of America unscrutinized. She was particularly wary of private equity investments in the U.S. healthcare system—which were recently the subject of a damning, 171-page bipartisan staff report from the Senate Budget Committee called “Profits Over Patients,” though it wasn’t clear if she was referencing that report’s conclusions, specifically. During her reign as F.T.C. chair, Khan said that she heard “a flood of concern from

healthcare workers, from E.R. doctors … about the private equity roll-ups that were resulting in worse quality care, higher prices. These are just market realities that are not going away.”

Meanwhile, Blackstone is busy minting money. “It was a heck of a quarter for us, one of the best in our 40-year history,” Jon Gray, Blackstone’s president and chief operating officer, told CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin on

Thursday. Blackstone’s distributable earnings for the quarter were $2.2 billion, up 56 percent year over year. “The key drivers of our business—fundraising, investing, realization—were all at the highest levels in two and a half years,” he said. “We’re very pleased with that. But what’s really exciting here is the sea change we’re seeing in terms of the openness from investors toward alternatives, toward private assets.”

To wit: In recent months, Gray said, there’s been an explosion of

interest from individuals, investors, and companies in both private credit and private equity. Four years ago, he said, Blackstone’s private credit business had $176 billion of assets. Today, it’s $450 billion. Blackstone, of course, is the largest alternative asset manager, with a market value these days of $214 billion, up some 39 percent in the past year. The firm’s co-founder, Steve Schwarzman, is now worth $57 billion, and Gray, his heir apparent, is worth

around $10 billion. (You can subscribe to my partner Marion Maneker’s fabulous Wall Power private email to learn about some of the art world masterpieces that Steve has been snatching up along the way.)

I suspect there’s some merit to Khan’s admonition, especially if the Senate report is to be believed. But I also

suspect her warnings will fall on deaf ears as we enter the Trump II era. Frankly, I don’t see anything on the horizon that can stop the alternative asset juggernaut. Sorry, Lina.

|

|

|

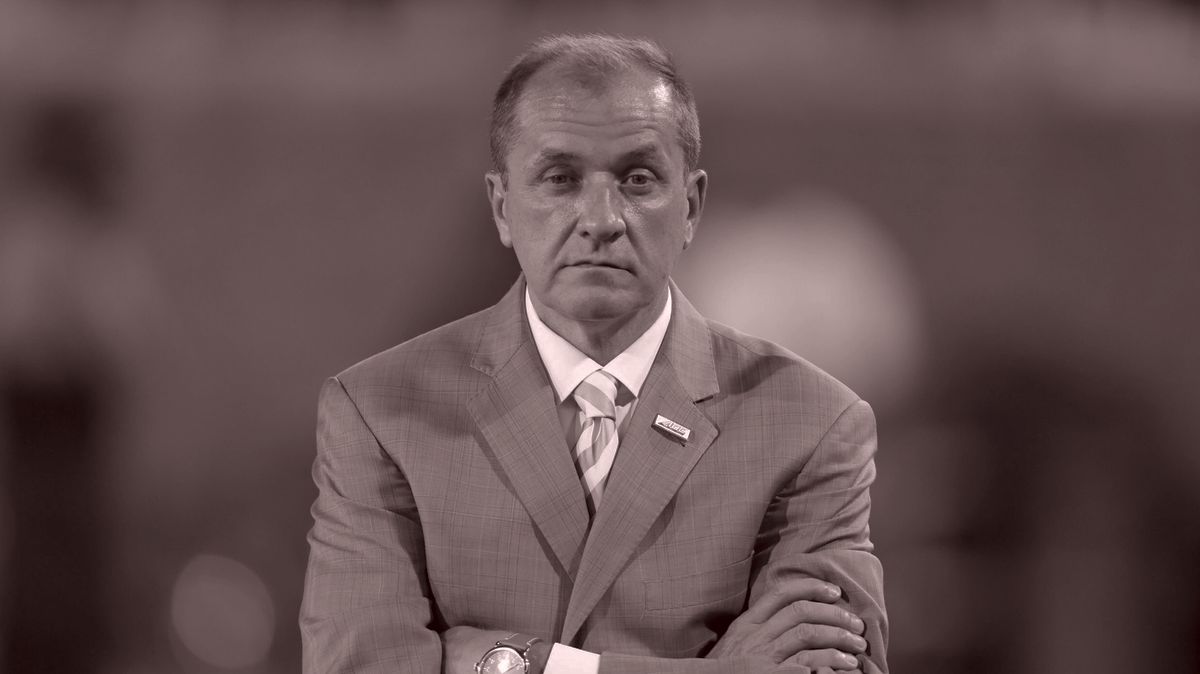

SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son is among the most enigmatic and

influential investors alive today. In a recent conversation at the Economic Club of New York, one of his biographers, the former FT editor Lionel Barber, offered a brisk primer on his legendary career.

|

|

|

Masayoshi Son, the multibillionaire founder of

Japanese investment company SoftBank, is one of the most intriguing, if utterly mysterious, businessmen on the world stage. He rarely gives interviews but is prone to grandiose pronouncements and even more grandiose investments—some of which have gone completely off the rails (WeWork), and others that have worked spectacularly well (Alibaba). But with SoftBank reportedly considering a staggering investment of between $15 billion and $25 billion in OpenAI—in addition to his recent

appearance with President Trump, Larry Ellison, and Sam Altman promoting a plan to invest $500 billion in U.S. A.I. infrastructure—Masa is suddenly very much in the news.

As luck would have it, Son is also the subject of not one but two new books: The Money Trap: Lost Illusions Inside the Tech Bubble, by Alok Sama, the former

president and C.F.O. of SoftBank; and Gambling Man, by Lionel Barber, the distinguished former editor of the Financial Times, who recently discussed his reporting at the Economic Club of New York. In conversation with Glenn Hubbard, the former dean of Columbia Business School and chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under George W. Bush, Barber explained that he decided to write the

book because of one word: money. Masa has “literally made or lost hundreds of billions of dollars,” Barber said. “He was the richest man in the world for three days at the height of the dot-com bubble, in February 2000, and in my experience in journalism: Follow the money. If there’s money around, there’s got to be a lot of good stories.” I certainly agree.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM GOLDMAN SACHS

|

Goldman Sachs Research expects worldwide GDP to expand 2.7% in 2025.

Factors driving the growth include:

– Rebalanced labor markets

– Slowing inflation

– Normalizing interest rates

Read the 2025 Global Macro Outlook from Goldman Sachs Research.

|

|

|

Barber’s path to Masa began a decade ago, during the process

that led to Nikkei acquiring the FT for $1.3 billion, or 44x earnings—yes, that’s the real price paid for a real newspaper. He made 14 trips to Japan over four years to cement the relationship between the FT and its new owners, and during those trips, he said, “I kept hearing about this figure, Masayoshi Son.” One or two people at Nikkei suggested looking into him, maybe doing a “Lunch with the FT” column. But, Barber said, “he was always elusive.”

That continued to be the case when Barber got to work on a biography. “It took a lot of work,” he said—at one point he told an Indian American investor that pursuing Masa was harder than stalking a Bengal tiger. (“‘In that case, Mr. Barber,’” he recalled the investor saying, “‘I would bring a goat.’”) He twice traveled to Tokyo to interview his subject, but “his people said, ‘He’s too busy,’” Barber remembered. “With Masayoshi Son, it was very

important to deliver a message: ‘Look, this isn’t an assassination. This isn’t a hit. I’m not interested in doing caricatures. I’ve done my homework.’”

|

Tokens in the Legend Meter

|

Despite his achievements, Masa remains an “outsider” among the

corporate elite in Japan. For starters, he’s Korean, not Japanese. His grandfather came to Japan in 1917, and his grandmother a decade later. “They were immigrants,” Barber said—economic migrants who took Japanese names to fit in, “literally fourth-class citizens.” His grandparents went back to Korea during World War II, then returned to Japan and spent the next decade destitute, with Masa’s father engaging in bootlegging, loan sharking, and then Pachinko. But by the 1960s, amid the postwar

“Japanese economic miracle,” Masa’s family was “quite well off,” Barber said, “although Masa likes to tell everybody that he grew up in a slum and he was really poor. That was actually quite a short time.”

The turning point for Masa was when he decided to finish high school in the United States, and then continued on to college at Berkeley. He learned English; he educated himself about the microchip and the burgeoning technology revolution; and

upon his return to Japan, he built a software distribution business, becoming a “middleman” between American technology companies and the Japanese market. He was close to Steve Jobs, which won him the exclusive right to distribute the iPhone in Japan. He cozied up to Bill Gates and Bobby Kotick. “‘You want to get into the mass consumer market in Japan,’” he told them, per Barber. “‘I’m the guy.

I can unlock the black box of distribution. I can be your cultural interpreter.’”

Then he started making bets of his own. He met Jack Ma in 1999 and made a big, early, $100 million investment in Alibaba. (He stuck with the company even after the dot-com crash, and made a fortune.) He made another big, early bet on Yahoo. And yet another big, early bet on

mobile phone technology, buying Sprint in the U.S. and then merging it with T-Mobile U.S. to create a viable competitor to Verizon and AT&T. In 2016, he bought Arm Holdings, “Britain’s best technology company,” Barber said, for $30 billion. Arm is now worth around $140 billion, and it’s “the platform for all [Son’s] ambitions in the A.I. space.”

In closing this last deal, Masa sought to meet Arm’s chairman on a yacht in the Bosporus, and planned to show up as he

did to other maritime billionaire tête-à-têtes—by landing his helicopter on the vessel’s helipad. “He’s obviously thinking it’s some kind of Russian oligarch’s superyacht,” Barber said. “And the poor English guy’s just got a sloop.” They ended up meeting in Marmaris, in Turkey. “Masa just hits him with a big cash offer, unconditional, and then makes two or three other offers, and that’s it,” he said. The entire sale process took two weeks.

Part of Masa’s strategy, Barber explained, is to

overwhelm founders with his financial largesse. “He says to Jerry Yang of Yahoo at one point, ‘You need $100 million.’ And Jerry Yang says, ‘No, I don’t need $100 million.’ And Masa looks at him and says, ‘Everybody needs $100 million. And if you don’t take it, I’m going to give it to your competitor.’”

Of course, that approach can also lead to expensive failures. Masa’s flood-the-zone strategy with WeWork’s Adam Neumann

blew up spectacularly and cost him billions. Masa “suffers from what I call ‘founder syndrome,’” Barber said. “If he meets somebody else who talks as big as he does, … and Adam Neumann talks big, … Masa just keeps piling the money in.” As Masa continued down the road with Neumann, there were few people inside SoftBank who were willing to challenge him, according to Barber, even though some believed Masa had to get out and that WeWork was not worth $47 billion. “Masa says, ‘That’s what everybody

said about Alibaba, and I was right,’” said Barber. “So he does get these things wrong.”

|

Masa is often described as the “Warren Buffett of Japan,” but Barber

says he has little use for the solid companies (like railways, Coca-Cola, other unimpeachable consumer brands, etcetera) preferred by the Oracle of Omaha. Instead, his appetite for risk favors high-tech gambles. “He is nowhere near Warren Buffett,” Barber said. In fact, Masa and SoftBank executive Rajeev Misra once flew from Tokyo to Omaha to meet Buffett and gauge his interest in contributing to their $100 billion Vision Fund, designed to disrupt the venture

capital industry. Buffett gave them a 20-minute tour and a 15-minute conversation. “Buffett essentially isn’t interested, and they fly out,” Barber said.

|

|

|

Eventually, of course, Masa did establish his Vision Fund—which

has had mixed results—largely from investors in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman. “There’s a convergence of interest between Masa, a capital hungry investor, and Mohammed bin Salman,” Barber explained. M.B.S. was looking to move Saudi Arabia’s economy away from fossil fuels and toward technological innovation, among other initiatives, as part of his so-called Vision 2030 plan. Masa was only too happy to oblige. “Masa likes to say—and he told

David Rubenstein this—‘I persuaded M.B.S. to give me $45 billion in 45 minutes,’” said Barber. “In fact, there was—and I document this in the book—quite a lot of diplomatic maneuvering … before they got the $45 billion. And even when they did get the $45 billion, there was a lot of negotiation about how it would be spent.”

In any event, over time, Masa became such an important symbolic figure in Japan that

the country’s establishment couldn’t let him fail—Japanese prestige became tied up in his success. Tadashi Yanai, the founder of Uniqlo, who served on the SoftBank board of directors for 18 years before his 2019 resignation, told Barber, in essence: “‘This guy was the icon. He was the dynamic entrepreneur. I thought I’d go on the board to help him and look after him a bit.’” The Japanese banks also gave him forbearance, and he started again. “He pivots

to broadband, gets the money, takes on NTT”—the incumbent telecom provider in Japan—“and Bob’s your uncle.” Masa is now worth somewhere between $20 billion and $30 billion, according to the usual suspects.

|

Inside the Sanctum Sanctorum

|

In the end, Barber managed to get four interviews with Masa,

totaling some nine hours of conversation. But he was careful to avoid embedding with him—not that the secretive Masa would have allowed that—and to get what he needed while keeping his distance. (He also interviewed about 150 other people.) He did, however, gain entrance to Masa’s private sanctum on the 37th floor of a Tokyo skyscraper, where Barber had heard he presented his guests with sushi that “some people say [costs] $30,000 or so,” Barber said. “So, I’m thinking I’ve got to find a way of

somehow getting into the inner sanctum to see this.”

But he didn’t want to ask Masa, lest he owe a debt to the subject of his book. In the end, Masa brought it up himself at the end of an interview. “We shook hands, and then he said, ‘I want to show you something,’” Barber recalled. “And he opened these doors, and there is this Xanadu meets Kyoto. There are three rock pools … and they’re

perfectly designed. There are trees with leaves painted individually, with gold tint. It’s an extraordinary thing, plus Japanese art. And, of course, of course, the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti wine, which is also $8,000 a bottle or so. There’s four bottles there by the dining table.”

Barber continued: “He took me round there, and then he said, ‘You can’t write a word about this.’ I’m thinking, ‘What!?’ So I said, ‘Why not?’ And he said, ‘Because no journalist has ever been in

this sanctum.’ And I then, without batting an eyelid, said, ‘But I’m not a journalist. I’m an author.’ Just kind of cheeky, but I got away with it.”

In any case, he thinks Masa liked the book well enough—the two ran into each other at the Allen & Co. conference in Sun Valley last summer and chatted; Barber introduced him to his wife. Masa did ask why Barber had called the book Gambling Man. Then he seemed to come around, musing aloud: “‘Gambling Man, Gambling

Man. I suppose I am Gambling Man. I suppose I am. Yeah, okay.’”

|

|

|

An insider-friendly tip sheet from Matthew Belloni, who spent 14 years in the trenches at The Hollywood Reporter

and five before that as an entertainment lawyer. Subscribers also receive What I’m Hearing+, a companion email focused on entertainment law, the streaming industry, and more.

|

|

|

Puck senior political correspondent Tara Palmeri grapples with the aftermath of what may be the most chaotic and

consequential presidential election cycle of our lifetime. With 15 years covering politics, Tara speaks with the smartest political minds to discuss what’s happening behind the scenes in Washington, D.C., from the campaign trail to the Capitol.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click

here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|

_01JH68YWRCKX6ZV950D2NTHN62.jpg)

_01JH8K9ZKGBPDWEMCZFMKZ77FV.jpg)