Welcome back to Wall Power and our Tuesday dispatch from the art

world. I’m Marion Maneker.

Tonight I’m returning to the subject of Giorgio Morandi—specifically, the extraordinary Magnani-Rocca Foundation collection of 50 works that David Zwirner has kindly brought to New York. The show is both an opportunity to look at Morandi’s market and a reminder that even some of the most

influential and popular artists’ markets can still be accessible—at least relative to what trophy art costs.

For my Morandi analysis, I turned once again to ARTDAI’s market data—a tool that I’ve found invaluable for understanding artists’ markets. For that reason, we’ve partnered with the firm to provide individuals access to their data. (ARTDAI focuses on institutional client relationships.) If you’re interested, inquire through

this link. We may get a commission if you sign up.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

PERFORMANCE UNLEASHED

With a distinct sporting personality, the Range Rover Sport is a

peerless performer.

EXPLORE

|

|

|

More on Morandi, below. But first…

|

- Nathan Drahi gets a promotion: Today, Sotheby’s C.E.O. Charles Stewart announced in an internal memo that Nathan Drahi, son of Sotheby’s owner Patrick Drahi, will assume the role of global head of business development on February 3. In that role, he will develop “holistic strategies for client management, with a particular focus on new client acquisition and growth, migrating toward a client-centric

business model, and increasing accountability and coverage frameworks to support our existing client base.” So what does that actually mean in practice for the young executive, who spent five years as managing director of Asia for Sotheby’s? He’ll oversee the valuations department and regional offices.

- Pace’s new space: Pace Gallery has announced that it will start sharing a space in Berlin this May, during the city’s gallery weekend. Together

with Galerie Judin—with whom it also shares representation of artist Adrian Ghenie—Pace will occupy a museum space originally built as a gas station in 1954, amid Berlin’s postwar reconstruction. The location will be led by senior director Laura Attanasio, who’s been in Berlin for Pace since 2023, and has been, in the words of the press release, “supporting institutional projects for its artists and deepening connections with collectors and arts communities in

German-speaking regions.” Pace plans to mount two public exhibitions a year in the new space, and Attanasio will relocate Pace’s Berlin office there in April.

- 2024 auction house market share: Now that Sotheby’s has released its 2024 results, we can do a rough calculation on market share for the four main houses operating in the U.S., which together reported $14.4 billion in sales last year. Sotheby’s pulled 41.6 percent; Christie’s was just behind, at

39.5 percent; Heritage clocked in at 13 percent; with Phillips at 6 percent.

I’m wary of providing market-share numbers for the auction business since, among other reasons, it’s hard to define what business we’re talking about. Sotheby’s and Christie’s are the dominant players—a duopoly, really—in fine art. But as we saw on Sunday, a large portion of Sotheby’s sales

comes from non-art auctions. Indeed, no two houses have the same mix of property in their results.

There’s also the issue of international sales. Heritage has offices abroad, but almost all of their sales are stateside. Phillips doesn’t break out their numbers by region. Christie’s doesn’t give us consolidated sales by region. The folks at Heritage asked me to give them some credit for their relative size in a business that somewhat ignores them because they’re based in Dallas and deal

primarily in non-art objects. But as I’ve said repeatedly—and will keep on saying—there’s a lot of cultural property out there that’s becoming more and more valuable. Heritage’s $1.87 billion in sales last year is almost exactly half of Sotheby’s $3.72 billion in U.S. consolidated sales, which gives you a sense of how important the collectibles market has become.

|

|

|

A second extraordinary show of Giorgio Morandi’s art has opened in

New York in the span of four months. Artists and collectors swoon over the Italian recluse’s muted masterpieces, but his auction market and prices have never followed suit. Will they now?

|

|

|

“This is our gift to New York,” said David

Leiber, a man not normally prone to grandiose statements, as Julie Davich and I toured the opening of Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces From the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, which is on loan to David Zwirner’s gallery space on West 20th Street for a brief five weeks. Leiber was explaining why Zwirner had borrowed the Morandis from the private Italian foundation and chose to present them as he had. The gallery, Leiber noted, likes to

show art with plenty of wall space around the individual work, which is quite different from the European salon style of exhibition. So the gift here was not merely the chance to behold these Morandis, but also to see them in a different context from how they were normally hung.

It’s a gift to anyone, even if you’re not an artist or collector—indeed, I’d recommend going back more than once, since Morandi benefits from

multiple viewings. The Magnani-Rocca Foundation’s unique collection of 50 Morandi works, which normally fills a villa in Parma, spans the range of his career and bears his personal efforts to shape his legacy, since Morandi helped select his own works for Luigi Magnani to collect. The latter was a musicologist, art critic, and collector born at the beginning of the 20th century to a mother with a noble lineage and a father who built a small fortune in the dairy industry.

Magnani’s refined bourgeois life was a contrast to Morandi’s cloistered existence in Bologna. But, as Leiber explained, Morandi’s work was represented by a prominent gallery and well known to art collectors throughout his lifetime.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

PERFORMANCE UNLEASHED

With a distinct sporting personality, the Range Rover Sport is a

peerless performer.

EXPLORE

|

|

|

The result is a collection that offers a capsule retrospective

of Morandi’s entire body of work. A printmaker, painter, and watercolorist, Morandi had three main subjects of his work: endless variations on tabletop still lifes, floral images, and landscapes. In the Magnani collection, you’ll see the delicate interplay between form and image.

Its presence in New York is the product of at least two years of effort by Leiber, who has an affinity for Italian art,

and noticed several years ago that the Magnani-Rocca foundation closed in the winter. So Leiber began the process of bringing Magnani’s Morandis to New York—no small feat, given that Morandi’s quiet, often gnostic work is jealously guarded by the Italian state, especially now that the defense of its cultural heritage has become a right-wing talking point for Giorgia Meloni’s nationalist government. Leiber was sweating export permits until the very last minute.

But in the end, he got them, and New York got its second spectacular Morandi show in the short span of four months. As Wall Power readers know from our interview with Mattia De Luca about his pop-up of Morandi’s work last fall, the first show offered a very different take on the same subject. De Luca was captivated by

the subtle differences and similarities, often decades apart, in the way Morandi treated his still lifes, landscapes, and floral paintings. De Luca gathered as much of Morandi’s work together as he could, to allow viewers to see the carefully calibrated use of light and color, and the artist’s exploration of the way forms could be presented to elicit emotions.

|

|

|

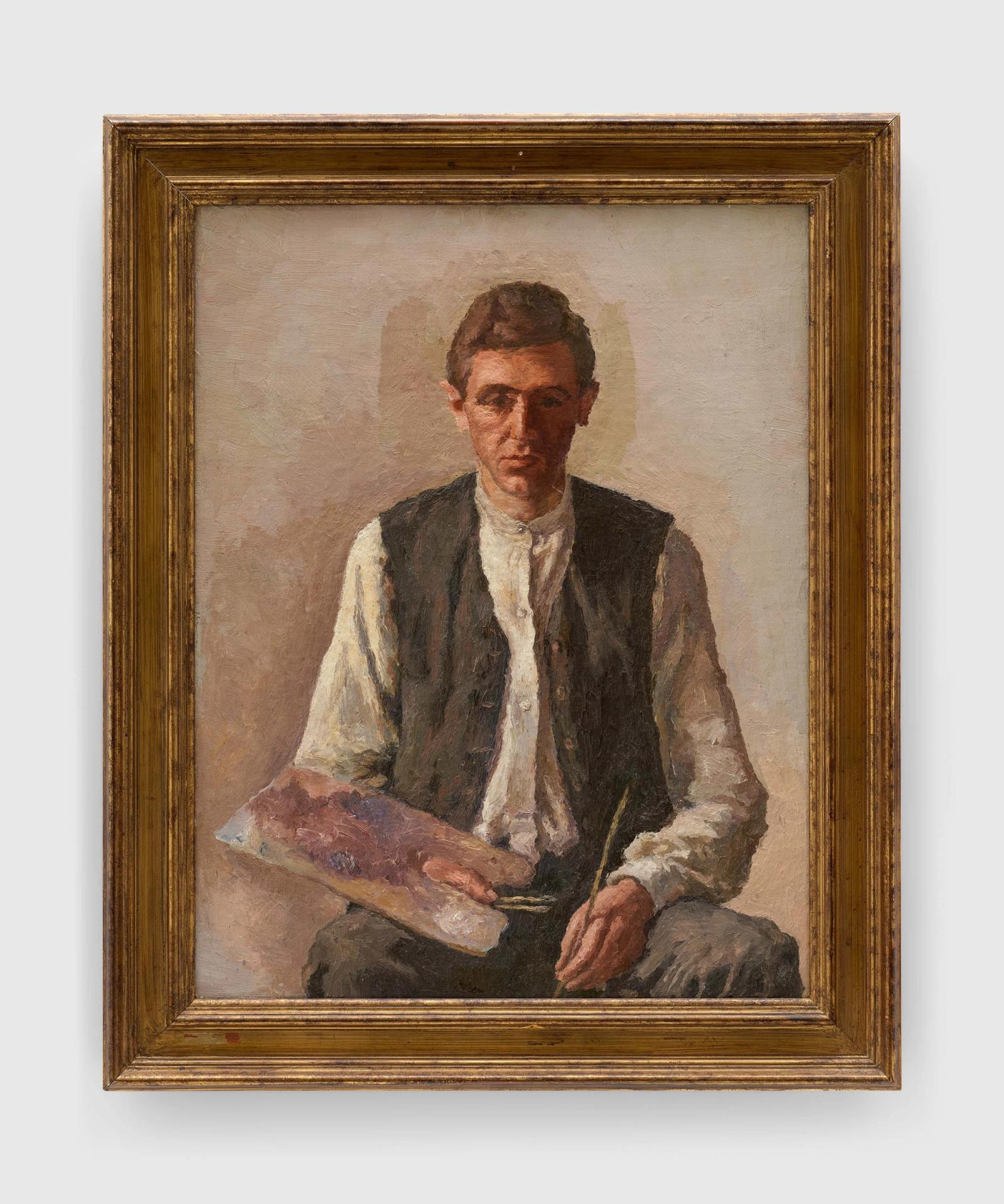

Giorgio Morandi, Autoritratto (Self-Portrait), 1925

|

In the Magnani collection, Morandi fans will see the artist’s extraordinary

technical skill. At one extreme is the incredible depth that Morandi achieved by varying the cross-hatching in his etchings. At the other is the minimalist abstraction of his watercolor still lifes and landscapes. In between, we see a landscape painting with half the canvas dominated by a blank wall, prefiguring pop art images that would come later in the 1960s, and another image of bottles standing like sentries in a metaphysical landscape, not to mention an actual metaphysical work from the

artist’s youth, and an enigmatic self-portrait. All of these works are presented in Morandi’s idiosyncratic palette of muted, unsaturated colors.

|

“A Park Avenue-Type of Painting”

|

None of the works in the Zwirner show are for sale, obviously. But

having two remarkable Morandi shows in New York in quick succession cannot but help generate more interest in, and demand for, the artist. There are only about 1,300 paintings. The etchings, for reasons I don’t really understand, trade at prices in the low five figures, sometimes falling below $10,000.

Sales of Morandi’s work began to pick up around 2007, the first year his auction volume topped $10

million. Overall auction totals would wax and wane until 2018, when the volume topped $20 million. The next year, volume stayed just above that mark, but the trend was unsustainable and auction sales fell below $10 million again, rising from just above $7 million in 2020 and 2021, to $11.8 million in 2023. Last year, Morandi’s auction volume dropped again, to just over $5 million.

But the falling auction volume is

less an indicator of evaporating interest than it is an issue of supply, and whether to sell at auction at all. That said, the average price of a Morandi over the past decade has steadily risen, even accounting for the usual oscillations in the market. Put another way, the highs are getting higher, and the lows are also getting higher.

|

|

|

In 2007, a 1920 Morandi still life set an auction record for the

artist of $2.7 million. In 2015, a 1939 still life was sold at auction for $3.9 million. Then, in 2018, David Rockefeller’s oval 1940 still life made an auction price of $4.3 million, defining the upper end of the Morandi market. Since then, a 1954 still life sold for $3.8 million in November 2021, and a 1959 still life made $3.5 million a year later. Meanwhile, another four works auctioned above the $2 million mark, even as the frequency of sales slowed, possibly reflecting the

combined efforts of De Luca and Leiber to match buyers and sellers on the private market.

When I asked De Luca about Morandi’s pricing, he cautioned that he was not a trophy artist. Important collectors like Rockefeller might own the works, but Morandi’s paintings and etchings are more quiet and contemplative than show-offy. Leiber added that the Italian government’s reluctance to see Morandis leave

Italy adds uncertainty for potential bidders and mutes the auction market.

Those are good explanations, but I decided to check in with a European collector who happens to be a real Morandi aficionado. He offered four reasons that Morandis don’t sell for big prices. First, “they’re intimate paintings,” he said, “not in-your-face, contrary to Fontana. It’s a bit like a smallish

Ryman—you might pay $18 million for a large Ryman, or a large Fontana, but not for a small one.”

Then there was the palette issue. The colors, he said, were “too subtle to please the current market.” And the muted tones read old money and conservative, “a Park Avenue-type of painting.” Also, although the Chinese began acquiring Morandi’s works more than a decade ago after the painter

Zeng Fanzhi started buying and his collectors followed, it’s still a very Italian market. (Though this collector said that the export-license issue wasn’t that big a deal since most of the prewar works—the ones the government keeps a watchful eye on—are already in museums.)

My informant’s final comment was startling, and encapsulated Morandi’s simultaneous blessing and curse.

“Morandi is a connoisseur’s artist,” he wrote, “and connoisseurs don’t make a market these days.”

|

I’m still scratching my head over

this column on crypto’s return to the art market that ran in the Financial Times last week. It raises an interesting issue with Sotheby’s eagerly courting crypto purchases in their upcoming Saudi Arabian sale, even though the $6.2 million sale of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian was arguably dampened by the fact that the buyer was a crypto

zillionaire. (It obfuscated the market price for Cattelan that the traditional world of money might support.) It also addresses the question of whether the Trump administration’s embrace of crypto could pave the way for the return of the N.F.T. market.

I’m skeptical: The N.F.T. boom was largely a function of the crypto rich needing a way to spend their gains. By trading through reputable auction houses that

operate Know Your Customer protocols on their clients, N.F.T.s allowed people to convert their crypto into fiat currency in an above-board way that the authorities would accept. Isn’t Trump basically promising to make that unnecessary?

Anyway, instead of focusing on all the ways that crypto’s resurgence has the potential to directly impact the art market, the FT oddly chooses to focus on

second- or third- order effects, like diversity. “The profile of these previous buyers—mainly young men—had also not sat well with a market grappling with its own lack of diversity,” the paper wrote. Huh? Most of the crypto buyers the FT discusses are young Asian men. In a Western-dominated art market, this all seems beside the point.

The FT then changed gears, making a meal of art market

myths. “Art’s appeal—in a secretive market that can turn volatile, on-paper profits into transportable, tangible assets—makes it already attractive to money launderers,” the reporting claims, “with N.F.T.s as a potential new playground.”

Actually, no. There’s zero evidence, despite years of publications repeating this canard, that art is a viable conduit for money laundering. The full explanation is

too long for this space, but the short version is that the art trade has limited capacity, and there are too many ways for hopeful money launderers to get cheated, themselves. In other words, in the art market it is easy to get taken, whether you’re a naive collector or a naive money launderer.

At any rate, it’s far too soon to perceive the impact that crypto’s rising value will have on the art market. More to the point, at this stage it looks

like the new frontier is the auction houses accepting crypto as payment, not whether N.F.T.s will roar back into the public consciousness. The crypto rich will now have greater access to converting their cyber wealth into physical assets, and the auction houses will be tasked with obtaining K.Y.C. assurances for these customers. That’s actually a good anti–money laundering protocol.

On that

bright note, I’ll see you back here tomorrow for our next Wall Power Inner Circle exclusive. Upgrade here, if you haven’t already.

M

|

|

|

The ultimate fashion industry bible, offering incisive reportage on all aspects of the business and its biggest

players. Anchored by preeminent fashion journalist Lauren Sherman, Line Sheet also features veteran reporter Rachel Strugatz, who delivers unparalleled intel on what’s happening in the beauty industry, and Sarah Shapiro, a longtime retail strategist who writes about e-commerce, brick-and-mortar, D.T.C., and more.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|