|

|

|

Welcome back to Wall Power, your twice-weekly take on the art world. I’m Marion Maneker, here to distract you with beauty and grandeur (or, at least, art world gossip) while you wait for the election results tonight (and maybe tomorrow and Thursday, too…).

There’s a lot going on in the art world as we enter the final two weeks before the November auction in New York. Phillips, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s have all put their auction catalogs online, so we now know what’s on offer. It will take a little time to digest, but I’ll have an overview sometime next week.

Today, I’m looking at collector Larry Warsh’s trove of Keith Haring subway drawings, which are being sold at Sotheby’s in two weeks. The auction house is going full multimedia with an “immersive exhibition” at its York Avenue galleries, powered by Samsung (Sotheby’s is always keen on a marketing partnership), that will put visitors back in the gritty NYC subway system of the early 1980s. I have a lot more to say about Haring and the subway drawings below.

But first…

- The Dallas Museum of Art is looking for a new director: Last month, The Washington Post ran a list of the 20 great museums in the United States. The list was filled with the usual suspects: The Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art topped the podium, while the lower reaches included some of the country’s most august institutions, many founded in the 19th century. One surprise on the list (at least to outsiders) was the Dallas Museum of Art. The Post called its collection “diverse and deep,” and its exhibitions “both popular and scholarly.”

Well, yesterday we learned that the DMA’s current director, Agustín Arteaga, who has been at the museum for eight years, is stepping down so the museum can conduct a search for his replacement. It should be a plum job: Museum directors make their mark as fundraisers, builders, and by acquiring trophy works for the institution. And the DMA gives an able director the opportunity to do all three. When I visited Dallas last week, everyone was asking how the museum was going to find the money to realize its plans for a 40,000 square foot expansion. Luckily, as I witnessed up close, there’s plenty of money in Dallas. Someone just has to go get it.

The job is in stark contrast to the post that just opened up at the Museum of Modern Art—possibly the most prestigious director position in America. The ideal candidate will have to reimagine how a great museum raises money, selectively acquires art, and connects to its constituency—and there’s no playbook for that. But MoMA also needs someone who no longer has the drive to build. It’s hard to imagine an ambitious museum director in their early 40s choosing the staid MoMA job over the opportunity in Dallas.

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

|

|

|

- Sotheby’s closes on the Breuer building… and opens a new set of questions: Suddenly, all the talk and speculation about Sotheby’s is less about its billion-dollar cash infusion and more about real estate. On Monday, the auction house announced, via The New York Times, that it had closed on the Breuer building. The story confirmed that Sotheby’s would be working with architects Herzog & de Meuron, who revamped the Tate Modern and the Park Avenue Armory, to update the former museum’s interiors.

One touchy issue is how much of Marcel Breuer’s interiors should be considered off-limits to renovation. The building’s interior is not landmarked, but the lobby may deserve that status, and Sotheby’s has to walk a fine line here, lest they jeopardize the goodwill and nostalgia they’re trying to capture. What would be the point of an auction house taking over a former museum only to subsequently be perceived as a poor steward of the architect’s legacy? “By reviving lost spaces, carefully inserting new ones and doing other subtle interventions with a considered palette of materials, the building will be prepared for its new role in the auction world and will also be more accessible again for visitors and the people of New York,” Jacques Herzog told the Times in what appeared to be a very carefully worded statement.

Maybe it’s Herzog’s Swiss-inflected English, but it’s not clear to me what the architect meant by “more accessible again.” Was there a renovation of the building that reduced access? Regardless, access might be the most important goal for Sotheby’s. Auction houses are notoriously intimidating to the general public, and Sotheby’s doesn’t want to squander the opportunity to welcome a new generation to bid on works of art—but also sneakers and handbags and vintage jewelry. Sotheby’s, after all, believes its future growth is tied to its ability to expand as a luxury retailer, and five years in, the auction house has only made small advances toward creating a walk-in retail environment. How will the Breuer be modified to that end?

These aren’t idle questions: Sotheby’s has invested heavily in new real estate in Hong Kong, Paris, and now New York, without any clear pathway for these capital expenditures to generate immediate revenue. That over-investment appears to have had a cascading effect, too, resulting in layoffs and requiring the firm to sell a substantial stake to ADQ amid declining auction sales and cash flow in 2024.

Sotheby’s has aspirations to become a larger luxury brand, and the investments in real estate may fit that thesis. Sotheby’s recently invested in a print magazine, which C.E.O. Charles Stewart believes can become a potential profit center. Likewise, making the Breuer building more accessible may also be linked to Stewart’s interest in generating revenue from a restaurant. The former uptown home of the Whitney Museum “has a long history of successful restaurants,” Stewart recently told Vanity Fair’s Nate Freeman. “We will do our own take on that.”

- Who consigned Kai Althoff’s painting?: I got a note from a keen market observer yesterday who wanted to alert me to the fact that the first significant Kai Althoff painting to come to market is being sold by Sotheby’s and has been consigned by Allan Schwartzman. Althoff was represented by the gallery of Barbara Gladstone, who was fiercely protective of her artists, and who died unexpectedly at the age of 89 while traveling to Paris in June. Gladstone had taken great care to place the artist’s work with collectors in order to keep it off the auction market, so it’s a surprise that Schwartzman is not selling through her gallery. To further complicate matters, Schwartzman is a trustee managing the art that Gladstone left behind. Emails to Schwartzman and Gladstone gallery were not returned.

- The search for Sarah Cunningham has ended: Pleas for information about the whereabouts of 31-year-old artist Sarah Cunningham began to appear on social media almost immediately after she went missing early on Saturday morning. Her brother filed a missing persons report, and early Monday morning, London’s Metropolitan police notified the family that a casualty had tragically been discovered on the tracks of the Chalk Farm Underground station. Our condolences to everyone.

|

| Rockefeller’s Joan Mitchells at Christie’s |

|

|

|

Joan Mitchell, City Landscape (1955), estimated at $15 million

|

|

|

| Rockefeller University has an art collection because the Rockefeller family was committed to the idea that art and science are intimately related. In 1958, the Manhattan-based university acquired two works by Joan Mitchell, City Landscape and an untitled work, both from 1955, in the hope that they would inspire the researchers who worked at the university. Now, the school is selling the two works with a combined estimate of $24 million to fund biomedical research.

This is not the first time that Rockefeller, which has a modest endowment of $2.5 billion, has sold art to fund professorships or research. And this sale shouldn’t be surprising given the new records recently set for Mitchell—in the last year, the top three prices for her work reached $22 million, $27 million, and $29 million at auction. City Landscape is estimated at $15 million and the untitled work at $9 million.

|

|

| Keith Haring’s Missing Market |

| Haring, the iconic New York street artist, became a pop culture icon but never developed a market to rival Basquiat, his more collectible contemporary. A sale of his subway drawings, at Sotheby’s, aims to change all that. |

|

|

|

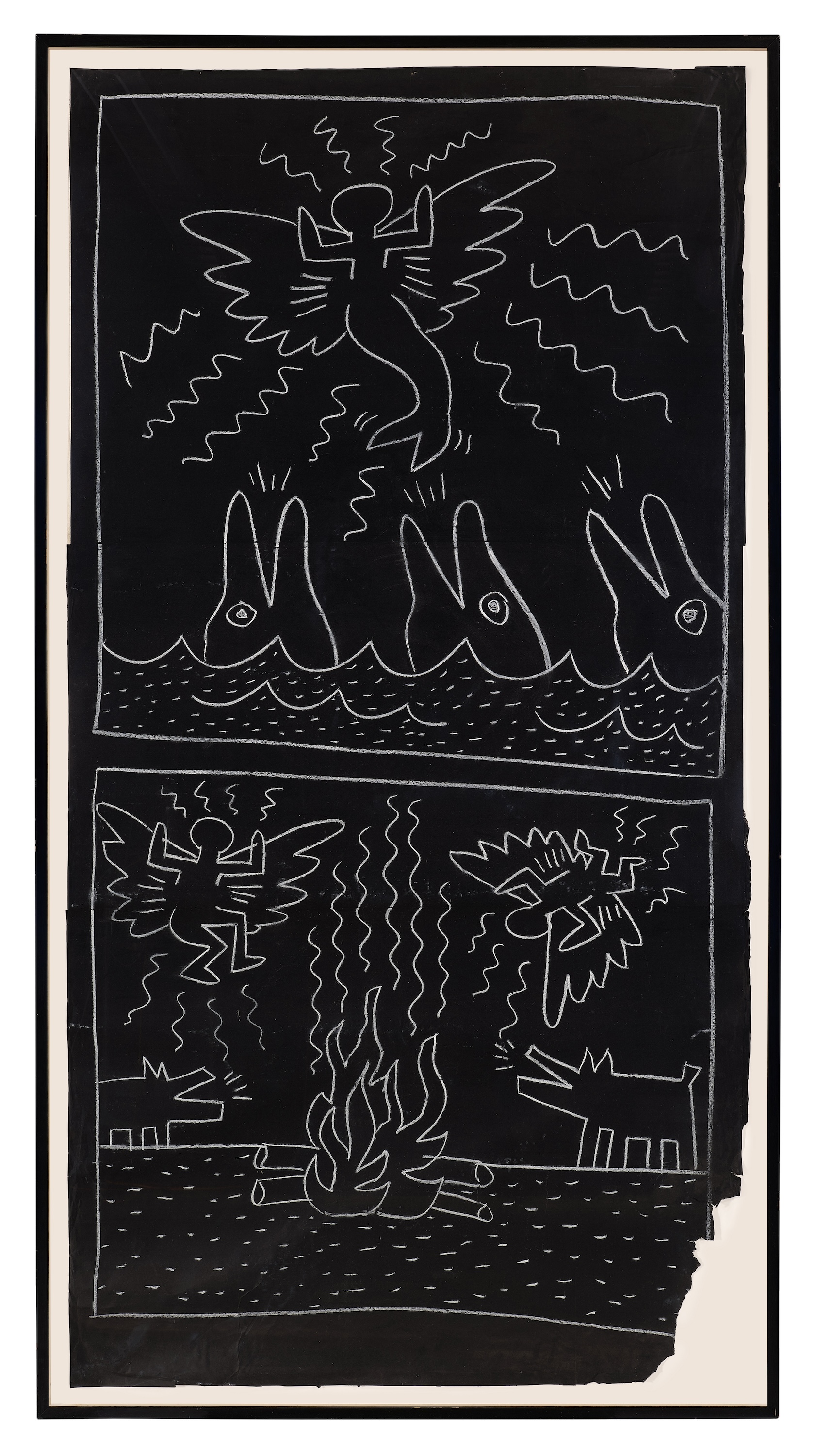

| Keith Haring is an enigma as an artist. Passionately committed to the idea that art is for everyone, he worked out the iconography of his art over a period of five years, drawing on blank advertising panels in the New York City subway system during the early 1980s while a student at the School for Visual Art. “He used the city as his canvas,” collector Larry Warsh told me.

That work—filled with his distinctive visual language of crawling babies, dancers, television and boombox-headed figures, spaceships and dolphins—was never meant to be collected. Who would collect drawings by an unknown artist killing time waiting for the subway? Even though his work was making him famous with New York City transit officers and subway riders, Haring would have preferred that the work get papered over with ads or fade into the patchwork of graffiti. And yet, as Haring’s art became beloved by New Yorkers, people began to pull down the drawings and save them. Haring’s response to the success of his accidental public art project was to collaborate with photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, who documented the drawings shortly after Haring left his trail of art across the Manhattan mass transit system.

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

|

|

|

|

| The resulting book of photographs, Art in Transit, might have been the only evidence of Haring’s formative years as an artist, before he started working with Tony Shafrazi’s gallery and, later in his career, making art on canvases that could be easily sold to collectors. Or they would have been, anyway, if Warsh had not spent the same period collecting the works as quickly as Haring could draw them.

Forty years after Haring emerged from the New York City graffiti scene, along with his peer and antithesis, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sotheby’s will be selling Warsh’s collection of 31 subway drawings during the November day sales. Across town at Christie’s, there’s a Basquiat drawing on paper from the same era, estimated at $20 million, that will go on auction during the evening sale. The most expensive of Haring’s subway drawings, by contrast, is estimated at $500,000. There’s one on offer for as little as $40,000.

|

|

|

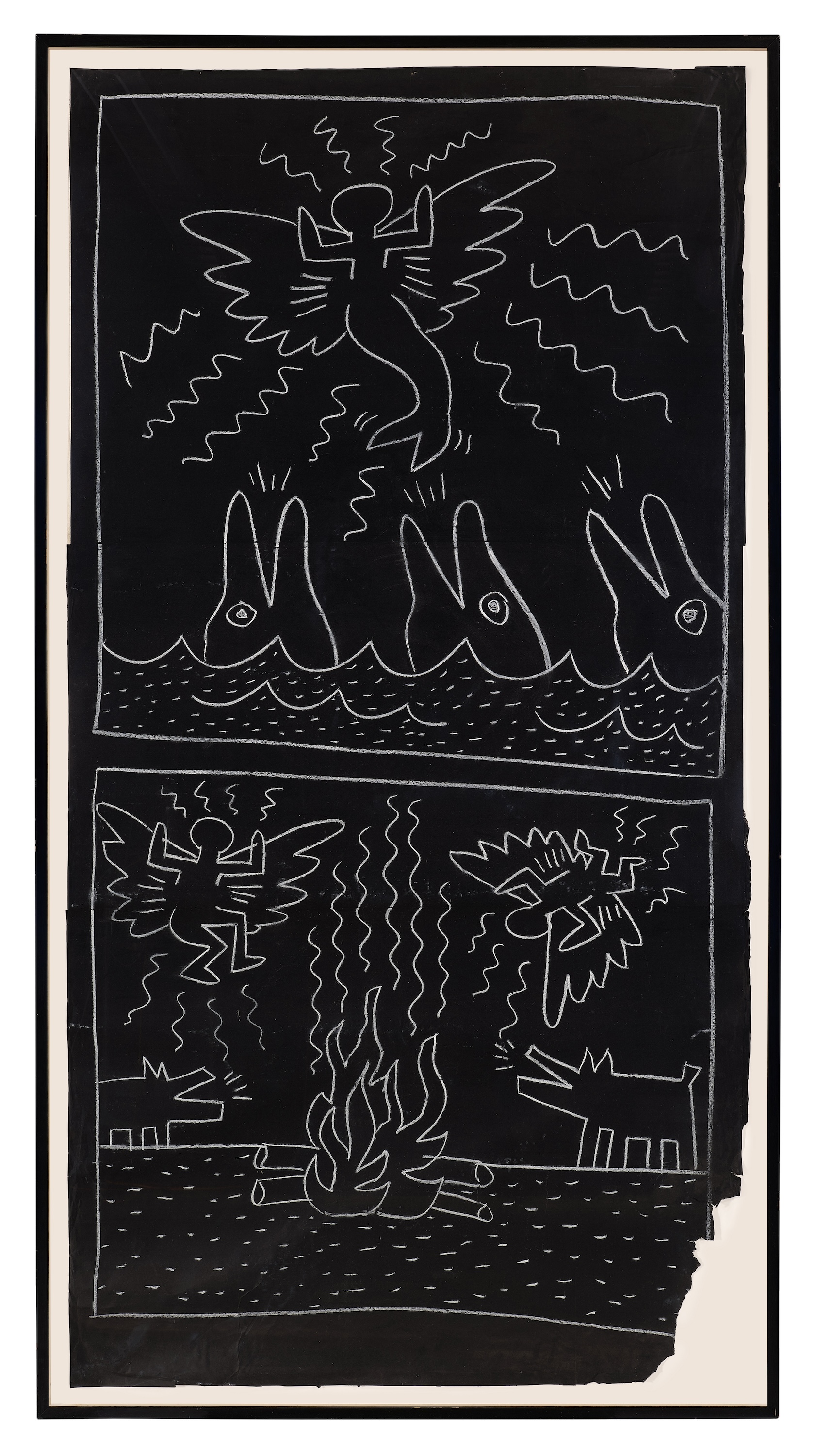

Keith Haring, Untitled (Still Alive in ’85), estimated at $500,000

|

|

|

|

|

| There are many reasons for the disparity in value between Haring and Basquiat, both of whom died around the same time. (Basquiat overdosed in 1988; Haring died of complications from AIDS in 1990.) The conventional wisdom is that Basquiat, who also painted on unconventional armatures of all sorts, made work to be sold in galleries. That was his goal. Haring’s mission to create art for everyone meant that even once his career had skyrocketed aboveground, as he said in 1984, “ The subway is still my favorite place to draw.” But there could be any of a dozen other reasons why fate has left us with a $110 million Basquiat and a $5.9 million Haring as their respective top auction prices.

In conversations about art, imagery, and the importance of the New York graffiti scene, no one would privilege either of these artists over the other. (Among the surviving works from that period, there is a subway drawing that shows Haring’s crawling babies and Basquiat’s signature crown.) In fact, in terms of direct impact on the art that festooned the New York City subways in the 1970s, Haring is clearly the more significant figure. “I arrived in New York,” Haring wrote in the introduction to the book documenting his subway drawings, “at a time when the most beautiful paintings being shown in the city were on wheels—on trains—paintings that traveled to you instead of vice versa.”

Haring spent two years looking at graffiti while he struggled as a young man to find his vision and voice as an artist. He tried performance; he tried video; he drew inspiration from William S. Burroughs and studied semiotics. Eventually, graffiti won out. There was, he observed, an “obvious mastery of drawing and color.” But what impressed Haring the most was “the scale, the pop imagery, the commitment to drawing worthy of risk and the direct relationship between artist and audience.”

As much as Haring admired graffiti art, he had no intention of “jumping on the band-wagon and imitating their style.” Instead, he would begin to paint on tarpaulins and other objects and conceive of more ambitious public projects. “With Keith, you have a world of mediums,” Warsh told me, “where the sum total is, ‘Wow, this guy is really smart.’” This point will be made when Crystal Bridges opens its exhibition, in March of 2026, in Bentonville. Keith Haring in 3D, curated by Glenn Adamson, will explore the wide ambit of a groundbreaking artist whose last concern was making paintings for collectors.

|

|

|

Keith Haring, Untitled (Mermaid – Angel, Dolphins, Angels, Barking Dogs) (c. 1981-83), estimated at $500,000

|

|

|

|

|

| Collectors, of course, play their own role in the career and reputation of an artist. Warsh, who was living downtown in the early ’80s, became obsessed with the work of Basquiat and Haring. (He would eventually sit on the Basquiat authentication committee before it was disbanded.) And with both Basquiat and Haring, Warsh did not have to consider whether their work was important. He knew immediately that it was.

If collectors have a role in culture, it is to see the future, or—as Warsh put it in the introduction to the catalog of the 2012 Brooklyn Museum exhibition of the subway drawings—to “recognize, with great clarity, that a given artwork or artist is … significant to the art and culture of their time. … Collectors, with their passion for discovery and confidence in their own tastes, sometimes have a knack for seeing ahead in this way.”

|

|

|

| In fact, Warsh’s defiance of Haring’s own preference that the subway drawings disappear under a palimpsest of advertising imagery is also part of what collectors do. (As Warsh put it, “They pull from the infinite stream of objects and images that cross their paths.”) What Warsh liked about the subway drawings is that they were not pristine and bear the “rips and wrinkles” of their origins in the dirty New York of punk rock and disco. Now, 40 years later, Warsh is selling the drawings to realize some value for himself after having held them for so long—the entire group has an estimate of more than $6 million and is backed by a Sotheby’s guarantee—though only Warsh knows how much money he has spent over that time storing the works, sponsoring exhibitions and catalogs, and otherwise promoting Haring’s legacy.

One of the advantages of the art market and auction houses is that their sales are also marketing for the value of the works that they have sold. In other words, Sotheby’s isn’t simply creating a virtual subway station of the era and showing archival footage of Haring at work. If the works sell for numbers much higher than their estimates (and they are clearly estimated to sell), the momentum will have an impact on Haring’s reputation. The strong sale of so many objects from the same body of work should raise interest in that body of work and the artist. Warsh would love nothing more than to see museums bidding and buying these drawings; it’s really the first chance they would have to do so. And that, as far as Warsh is concerned, is the best route to archiving Haring’s art for everyone.

|

|

|

| Okay, that’s probably more than enough for Election Night.

One last thing, though. I’ve heard from a couple of you about the crypto community brouhaha surrounding Michael Bouhanna, Sotheby’s head of digital art. (See what I did there?) Before posting about the Comedian (Ban) memecoin on Sunday, I spoke to Bouhanna about his role in launching the coin, his positive tweets about Maurizio Cattelan’s artwork Comedian, and the fact that he was behind the scenes launching the tokens for Comedian (Ban). He told me he has not realized any money from the launch. And I have no evidence that casts doubt on his claim.

Around the time of our conversation, he posted a longer explanation on Twitter/X. For reasons of space and not fully understanding much of how the crypto world works, I decided not to include that information in my small item about the tokens. (I’m still primarily interested in their predictive value; the current market cap is $22 million.) Others feel differently. I got more than one email pointing to Bouhanna’s role. The criticism seems to center on the fact that Bouhanna used a high-profile account to promote the artwork while he was anonymously creating the tokens and sharing the token with friends who appear to have spread the word. (For what it’s worth, the tokens weren’t launched until after the first tweet.) According to one of Bouhanna’s critics, “It either betrays a naiveté about how it would be perceived or an undisclosed profit motive. Both bad looks.”

You can decide for yourself whether this is a crypto world controversy or a real transgression while you wait for next week’s installments of Wall Power.

Speak to you then,

M

|

|

|

|

| FOUR STORIES WE’RE TALKING ABOUT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Comcast’s Stunner |

| Assessing the viability of Comcast’s spinco concept. |

| WILLIAM D. COHAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQs

page or contact

us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

|

|

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 227 W 17th St New York, NY 10011.

|

|

|

|