|

|

|

|

Forward this email to a friend!

|

|

For our second anniversary, subscribers can share the benefit of Puck with an exclusive code (INSIDEACCESS) that gets your network 30% off.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome back to In The Room, I’m Dylan Byers.

|

|

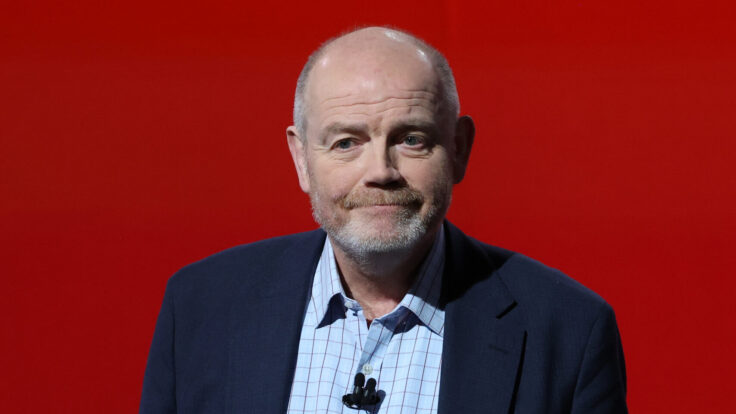

In tonight’s issue, a close look at CNN’s next leader, Mark Thompson, whom colleagues at both the Times and the BBC have described as a “philosopher C.E.O.” But will his unique skill set be enough to reverse the fortunes of the struggling network?

|

|

|

| In the summer of 2020, shortly before Mark Thompson stepped down as chief executive of The New York Times Co., he gave an interview to CNN from a charmingly spartan kitchen in western Maine and was asked to reflect on the resoundingly successful tenure during which he’d helped the Sulzbergers transform their indebted, moribund print paper into a profitable, subscriber-supported digital news and lifestyle brand. Thompson, a veteran of British television who’d served as top executive at both Channel Four and the BBC, entered the job with no experience in American media and, indeed, no experience running a for-profit company. Yet in eight short years, the Times had amassed 6.5 million subscriptions. In the process, the company more than quadrupled both its digital-only sub revenue and the $NYT share price.

In the interview, Thompson was asked to explain what he’d noticed about the Times business in those early days. “I just felt—and I feel this about TV,” Thompson began, “just like TV, I felt that the newspaper industry was trapped in a psychology of the limits of the possible.”

The insight and its phrasing befit Thompson’s self-styling as a public intellectual; former Times and BBC colleagues describe him as a philosopher C.E.O. who, in addition to successfully steering two of the world’s most storied news institutions, wrote a book about political rhetoric and serves on the board of the Royal Shakespeare Company. (Beyond Maine, Thompson has homes in London and on the Upper West Side.)

More importantly, of course, Thompson’s diagnosis exquisitely summarized the parochial mindset that beset the Times a decade ago. “The possibility that we’d have multi-million digital subscribers—I was in the meeting when those goals were set, and all of us thought, ‘Really!?’” Dean Baquet, the Times’ former executive editor, told me. “I thought we were setting targets that were unreachable... it turns out the possibilities were much bigger than we thought.”

Next month, Thompson will take over as chairman and C.E.O. of CNN, an institution that is still very much beset by parochialism owing to its addiction to a dying business model. For the last decade, while Thompson and his successor Meredith Kopit Levein were transmogrifying the Times into a best-in-class digital media behemoth, CNN’s leadership was largely preoccupied with mitigating the decline of the cable bundle and sustaining short-term profits.

The execution varied greatly, of course: Jeff Zucker drove record high ratings and more than a billion dollars in annual profits, albeit via some self-aggrandizing theatrics; Chris Licht alienated the audience that Zucker had built, missed his revenue targets, and brought CNN to a reputational nadir. But in both cases, CNN was mostly fighting for a few million septua- and octogenarians—or, under Licht, hundreds of thousands of them—while the far more pressing question of CNN’s post-linear future was never prioritized as it had been at the Times, which now boasts nearly 10 million paying subscribers. (Some CNN execs believed CNN+ would become a thriving subscription business, a debate rendered moot by WBD’s decision to kill it in the crib weeks after he took over. Alas, even the most generous assessment is that the first stab at the business was rushed and expensive.)

David Zaslav’s decision to pivot from a programmer C.E.O., like Licht, to a digital transformation C.E.O., like Thompson, reflects an understanding—better late than never—that the metrics of success in this business are changing, and that CNN’s challenges go well beyond questions about partisanship or what to do at 9 p.m. Indeed, in the post-analog landscape, the Times and CNN will largely be competing in the same arena. Thompson’s former colleagues say that, in addition to being steeped in the arts of television, he possesses a brilliant grasp of those larger challenges: “He sees the battleship on the horizon and knows how to maneuver it,” one Times executive who worked closely with him told me. Said another: “He understands why traditions exist and why traditions need to be interrogated and overturned. Most people don’t get those two things right.” |

|

|

|

|

| Of course, Thompson will still face novel challenges. The BBC exists by decree of royal charter and is funded by the British public; the Times Company is controlled by the Sulzbergers who, as Baquet noted, “don’t think in terms of next year,” but rather in terms of, “what will my daughter inherit?”

CNN, by contrast, is a shrinking asset of Warner Brothers Discovery—a debt-saddled, $32 billion entertainment conglomerate (some $75 billion in enterprise value) that is obsessed with debt servicing and free cash flow, and that is almost certain to merge with, or be acquired by, one of its rivals before the end of the decade. WBD is also trying to justify CNN’s value in a post-cable world where news is a commodity that arrives via push notification. Indeed, up until a few weeks ago, when Semafor reported that Thompson was the leading C.E.O. candidate, the conventional wisdom among media executives and others in Zaz’s milieu was that he might sell the asset. (In fact, Zaz knew what he was doing all along; he reached out to Thompson days after ousting Licht, per sources familiar.)

These challenges now sit squarely on Thompson’s desk. Zaslav has promised him broad autonomy over CNN, sources familiar with their conversations told me. And, indeed, Thompson would not have taken this job if he didn’t intend to impose dramatic transformations that more thoughtfully align CNN’s editorial efforts with its business ambitions. At the Times, Thompson helped establish greater coordination between business and editorial—an effort made easier by the shift toward a subscription model—but never had the total oversight that he so obviously longed for. (“He would have loved to have had Dean’s job,” one Times source said.) Thompson will have that oversight at CNN, acting not just as chairman and C.E.O. but also, as the formal announcement states, “as editor-in-chief, ultimately responsible for all CNN content.” The new CNN will be Mark Thompson’s CNN, just as the old CNN was Jeff Zucker’s CNN.

Still, Thompson’s most important decisions may be more prosaic than his past philosophizing about innovation suggests. Some veteran media executives described Thompson as a decisive leader with deserved reputation and credentials, but not necessarily an innovator or digital visionary. And, indeed, even at the Times, he was one among a group of leaders—including Kopit Levein, who he hired in his first year—who helped reverse the organization’s fortunes. Baquet described Thompson as “a convener” and “talent scout,” and said his greatest strength was “bringing people together” and “shrinking a list of problems.” Presumably, nothing will be so critical to Thompson’s success as the executive team he builds around him. “My guess is he doesn’t know the answers [to CNN’s challenges] yet,” Baquet said. “What he does know is that the place is going to have to change mightily, and he’s going to need people inside to help him figure out what that looks like, and what the possibilities are.”

Of course, Thompson will still need people who understand the network’s inner workings, as well as those who know how to make good television. The dark arts of this business—the programming intuition, the booking tactics, the talent fluffing—won’t disappear in the new era, even if the talent is smaller and the resources tighter. And, anyway, Thompson still values those things. Both Times and BBC colleagues describe him as a television animal at heart. “The man is a genius [at television], and ruthless in executing,” one former BBC colleague told me. “In terms of his day-to-day, his television experience will be much more [significant]. The New York Times experience will be a lot of the digitization, and making money on that.”

Nevertheless, as Thompson hones his strategy, it’s hard to imagine that the old guard of television veterans will have the same authority they once enjoyed as the economics of ratings and ad sales play second fiddle to the streaming strategy, nailing CNN.com, and figuring out a disciplined D.T.C. approach. The quadrumvirate interim leadership that has gracefully steered CNN through its post-Licht transition—some of whom may have harbored their own ambitions for the C.E.O. chair, and who were thus miffed at not being interviewed for the top job—may soon find that they’ve been playing too narrowly inside the confines of the possible, and that their talents, while still highly valued, are no longer the business. |

|

|

|

| FOUR STORIES WE’RE TALKING ABOUT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQs

page or contact

us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

|

|

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 227 W 17th St New York, NY 10011.

|

|

|

|