Welcome back to Dry Powder. I’m William D.

Cohan.

When I called up Larry Summers, the former Treasury secretary and president of Harvard University, to discuss the game of tariff chicken that Trump is playing with China, Canada, and Mexico, he called the stunt, rather fittingly, “surreal performance art.” Indeed, among the many Wall Street insiders I polled about this half-baked scheme, this was the

prevailing sentiment. Perhaps not surprisingly, though, many top bankers have a far more nuanced view of the current tariff sitch—a topic that I’ll be exploring tonight.

But first…

|

- Got an idea for you, Brian!: Peter Supino, the respected media analyst at Wolfe Research (and the nephew of my former boss at Lazard), fired a ballsy warning shot at Comcast C.E.O. Brian Roberts this week. In an open letter, Supino suggested that Comcast’s controlling shareholder break up his company into three parts—going much further than Brian’s decision to create a “well-capitalized” SpinCo

composed of NBCU’s cable networks, including both CNBC and MSNBC but minus Bravo. The Supino thesis, a considerable expansion on an idea he first floated five years ago, calls for carving out Comcast’s cable distribution business and combining NBCU and Sky News, in addition to creating SpinCo.

Notably, Supino’s open letter followed Comcast’s disappointing fourth-quarter earnings report, which revealed larger-than-anticipated losses in broadband subscribers, plus flat subscriber growth in

its streaming business, causing the stock to tumble 11 percent in one day. (My partner Matt Belloni offered an acute analysis, as ever, in his recent piece Kabletown at a Krossroads.)

Supino’s note was unprecedented for its audacity, given the fact that the guy is challenging a seasoned management team from his perch as an

analyst rather than as an activist investor with his own capital at stake. And, for what it’s worth, it was filled with compelling ideas. For instance, Supino pointed out that Comcast peers Disney, WBD, and Charter all trade at higher EBITDA multiples (Disney trades at 13x estimated 2025 EBITDA, WBD trades at 6.7x, and Charter at 6.5x. Comcast, meanwhile, trades at 5.7x), noting that if Comcast were weighted proportionately and traded at an average of its multiples, its stock

would rise 57 percent. “We believe that the market discounts Comcast’s value severely because of concerns about returns on capital and instances of misalignment of leadership and shareholders,” he wrote. “We truly believe that as long as Comcast persists as a conglomerate, such concerns are likely to hamper the stock.” (Usual disclosure: This is not investment advice.)

Supino doesn’t see much growth potential in Xfinity, or from the broadcast networks, the cable networks,

Peacock, and Sky, unless equity incentives are reshuffled to better align leadership and shareholders. He was also highly critical of Comcast’s M&A strategy, estimating that Comcast spent $93 billion to acquire NBCU and Sky and to stand up Peacock, and that together they generate $7.5 billion of EBITDA, which the market values at 5.7x EBITDA, or $43 billion—“a $50 billion mark-to-market loss,” he wrote. He was also critical of Brian’s $340 million in cumulative compensation over the last 10

years and his failure to invest in the Comcast stock during that time. His 40.8 million Comcast shares represent 1 percent of the shares outstanding. Meanwhile, he controls 31 percent of the vote.

Supino wrapped up his jeremiad with some familiar notions. “We believe Comcast’s financial strength has provided false comfort to NBCU, and that the business independently funds its own growth investments,” he wrote. “While Universal has made great films and theme parks under Comcast and while

Peacock is a beautiful service, NBC/Universal was late to streaming and lacks the scale to win against YouTube, Netflix, Amazon, and Disney. NBCU’s EBITDA of more than $7B is more than enough to fund growth and negotiate potential strategic mergers.”

Anyway, dividing Comcast into three parts is an interesting idea, to be honest, and one that Brian should consider seriously, even if he likely won’t. Supino texted me yesterday that his report “elicited more reads than any company-specific

report I’ve ever published. It’s the only time in my career I’ve ever written an opinion that elicited 100 percent positive feedback.” A spokesman for Comcast declined to comment.

- The Wall Street revolving door: Two more senior Wall Street executives are leaving cushy posts to join the Trump administration. Last week, Trump announced that billionaire Stephen Feinberg, the C.E.O. of private equity firm Cerberus

Capital Management, would be joining his administration as deputy secretary of defense, and that Morgan Stanley’s Michael Grimes was headed to the Commerce Department in a yet-to-be-specified “senior role.”

Grimes, the co-head of Morgan Stanley’s technology banking group, is Elon Musk’s favorite banker, or so they say. He famously steered the I.P.O.s of Facebook and Uber, and advised Musk on the $44 billion acquisition of Twitter. (That should get Grimes

a demerit, not a job in Washington, but whatever.) Grimes will be working for Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, the former C.E.O. of Cantor Fitzgerald, while Feinberg will be subordinate, unbelievably, to Pete Hegseth at D.O.D. (Feinberg had a stint during Trump’s first administration as head of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board, whatever that is.)

I rang up a former private equity bigwig who worked in the Biden administration

to see if he had insight into why Feinberg and Grimes would leave their lofty perches to report to the likes of Hegseth and Lutnick. “They get a lot of power, and it’s cool,” he said. He also noted that both of these guys will probably avail themselves of the major benefits afforded people from the private sector who go to Washington in senior roles. Specifically, the ability to convert their net worth into Treasury securities on a tax-deferred basis, with the tax being paid only when the

Treasuries are sold, if they are sold. It’s a huge present-value savings, especially for a billionaire like Feinberg, who has enormous unrealized capital gains from creating Cerberus, and presumably, too, for Grimes, who has done extremely well at Morgan Stanley.

|

|

|

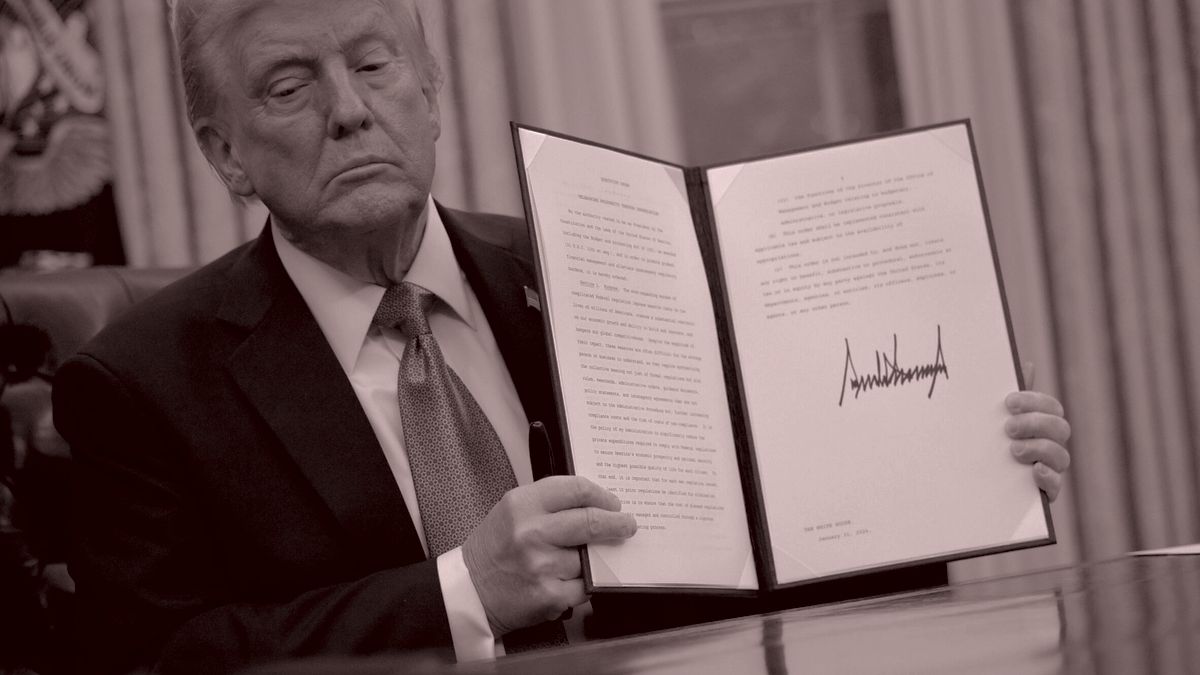

Other than the blanket pardons for the January 6 offenders, and

Trump’s D.E.I. press conference after the horrific helicopter-jet collision, the donor class on Wall Street is generally happy with Trump II.

|

|

|

Earlier this week, I was chatting with Larry

Summers, the former Treasury secretary and president of Harvard University, from his home in Arizona. During our chat, I asked him to describe the game of tariff chicken that Donald Trump has been playing with China, Canada, and Mexico. “Surreal performance art would be the term that I would use,” Larry told me, without missing a beat, expanding on the

opinion piece he co-authored last week in The Wall Street Journal with former senator Phil Gramm, urging Trump not to follow through with his tariff threats. (On Monday, Trump agreed to hold off for 30 days on imposing 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada after extracting

symbolic concessions from both countries.)

My conversations with bankers and other former government officials elicited similar responses. One Wall Street executive, who almost went to work for Trump this time around, artfully told me that the president was simply using the Oval Office and the media as his bully pulpit, itself a form of performance art. “Bullies love to see people cower in fear,” he said. “Why be a bully if you can’t do that? So how much of this is

just, ‘Justin Trudeau, I’m gonna fuck with him,’ or ‘Mexico didn’t really do shit to stop immigration, time for them to shit their pants a little bit. Let’s get a reset’?”

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM GOLDMAN SACHS

|

Find a competitive edge with insights from Goldman Sachs’ top economists and strategists.

The

Outlooks provide a thorough examination of market trends, regional developments, and sector-specific forecasts.

Read the Outlooks.

|

|

|

A former Wall Streeter who did a stint in Washington described

the first two weeks of Trump II as “a giant blender” of “fog and chaos” stirred up to distract people from three of Trump’s near-term goals: getting his “idiot cabinet picks” through the Senate; positioning Russ Vought, Trump’s pick to head the O.M.B., to “take the shit out of the budget”; and getting congressional approval for the extension of the about-to-expire Trump I tax cuts. And, he said, Wall Street is on board. “[The tax cut extension] is what they really want,” he

explained. “Until he can’t do that, they’re perfectly happy to back him and focus on the things that warm their hearts, like shutting USAID. But if this goes on too long and/or the stock market goes down, they’re not going to be so pleased.”

Another veteran Wall Street banker, who worked for Trump back in the day and knows him well, offered a more nuanced assessment of the tariff situation, as well as the

view from the upper echelons of Wall Street, which has been conspicuously silent. There are two types of people who work for Trump in Washington, he told me—“those who love tariffs, and those who are afraid to tell him the truth.” He said he has no idea what Trump “is trying to solve for,” but his hypothesis is that Trump was trying to follow through on a campaign promise and assuage his supporters who have lost manufacturing jobs, and who may believe that tariffs will reverse macroeconomic

trends and reopen factories.

In this regard, the veteran banker viewed the president’s motivations as genuine rather than theatrical: “He thinks those people who lost those jobs, and those steel mills, should be back, because it’s unfair that the Chinese are producing steel and polluting the air and not paying people living wages, and selling steel cheaper in the United States than we can produce it here.” Did he think it would work, I asked?

“Probably not,” he averred. But it may not matter: Most voters are likely to remember the theater of the tariff threats, but fewer will notice when they are rolled back or postponed.

Trump, the banker continued, was only considering “the part of the equation he wants to look at”—obsessing over lost manufacturing jobs while seemingly ignoring that technology and service sector jobs have grown G.D.P. and lowered the unemployment rate during

the past quarter-century. Indeed, many on Wall Street privately recognize that Trump has hyperbolically oversimplified a nuanced issue. To wit: Americans who rely on Walmart for low prices would never knowingly support tariffs that affect our supply chain relationships with Mexico and China, likely passing on the higher costs to them. “So at the same time he’s trying to help them, he’s hurting them,” the banker said. “The price of everything they’re going to buy is going to go up

dramatically—tomorrow. And that steel mill, if it comes back, will take five to 10 years to come back.”

Sure, consumers could buy domestic… in theory. But there are many commodities for which there is no “Buy American” option. “We don’t make athletic shoes in the United States,” my smart Wall Street source explained. “You can buy a Nike, or you can buy an On, or you can buy a New Balance, but they’re all made offshore.” The same goes for

cellphones, which are mostly made in China, and a million other consumer goods. “That cellphone that retails for $1,500 in the United States, it’s made for $500 to $600 in China,” he continued, noting the complexity of global supply chains and the depth of Asia’s manufacturing base. “If we needed to make that cellphone in the United States, it would cost over $2,000, and it would retail for $4,000.”

Trump not only dismisses or misunderstands these obstacles, he also

underestimates the resulting inflationary pressure, both from the tariffs themselves and any retaliatory actions by other countries—which are inevitable. “He does believe tariffs work, but when he sees the reaction, he somehow is always surprised,” the banker explained. “He keeps telling people that there shouldn’t be a reaction, but there is a reaction. Then he backs off” and claims a concession. He told me that he suspects White House staff were working overtime with the Mexicans and

the Canadians to extract anything that could be spun by Trump as a quick victory. (The White House did not respond to my request for comment.)

|

Amid our conversation, I wondered, did the financially sophisticated people around

Trump overlook these issues, or were they playing a longer game? And here, in particular, this veteran banker had a fascinating view.

|

|

|

A MESSAGE FROM GOLDMAN SACHS

|

Goldman Sachs economists and strategists share insights on the key factors driving the global economy.

What

to expect: Market-by-market, region-by-region, sector-by-sector analysis for the year ahead.

Read the Outlooks.

|

|

|

Wall Street doesn’t like or want tariffs, per se—“There

are only losers with tariffs,” the banker said—but many accept them as part of the price of doing business with Trump. Indeed, many machers preferred Trump II over Biden or Kamala Harris. “To me, it was a prisoner’s dilemma,” this person continued before articulating the internal monologue in the highest ranks of the banking industry. “We had an anti-business Biden opportunity, or a pro-business Trump, who may put tariffs on, or may not. But if he puts them on

and he realizes they’re bad, he may take them off within 24 hours. So they said, ‘We’d rather deal with Donald Trump because he’ll take our phone calls and we can tell him how bad these are, whereas Joe Biden won’t take our phone calls.’ Corporate America felt like we could sway Trump. We could get to him, and convince him that these tariffs are wrong.”

In fact, other than the blanket pardons for the

January 6 offenders, and Trump’s press conference where he blamed the fatal helicopter-jet collision near the Potomac on D.E.I., the donor class on Wall Street is generally happy with Trump II, according to this banker, a reality that much of the media still refuses to comprehend. “There are very good reasons to criticize D.E.I., but in this context, it’s a little insane,” he said, referring to Trump’s post-crash commentary. “And insulting and in bad taste.” On the other hand, he continued,

“everyone is thrilled” that the “apple cart” at USAID is getting turned over and that people are seeing who is getting paid what from the Treasury—“sort of all that DOGE stuff,” he said, which Wall Street types are giving “a standing ovation.”

But given the largely foreseeable chaos of the past few weeks, was there anything else that motivated the Wall Street donor class to lean so heavily into Trump last November, I wondered? “They don’t think being rich is

enough,” one of my sources told me. “They think they need to be venerated for being rich, and Biden didn’t venerate them for being rich. The idea that wealth equals merit tends to be appealing to the wealthy. They want wealth accumulation to be seen as making them like Einstein or Leonardo da Vinci. These guys are trying to be Averell Harriman, but they’re going to end up being Bebe Rebozo.”

|

|

|

An insider-friendly tip sheet from Matthew Belloni, who spent 14 years in the trenches at The Hollywood Reporter

and five before that as an entertainment lawyer. Subscribers also receive What I’m Hearing+, a companion email focused on entertainment law, the streaming industry, and more.

|

|

|

Puck senior political correspondent Tara Palmeri is here to help you get through what may be the most chaotic and

consequential presidential election cycle of our lifetime. With 15 years covering politics, Tara speaks with the smartest political brains to discuss what is happening behind the scenes in Washington D.C., and on the campaign trail.

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click

here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|