|

|

Welcome back to Dry Powder.

|

|

And thanks as always for supporting our work here at Puck. If you’ve got a friend or colleague who’s interested in a group subscription, we now offer enterprise accounts. Just have them email fritz@puck.news.

In today’s column, the astounding conclusion of the great Warren Buffett-Goldman Sachs mystery beef—a story about bankers and their fees that also reveals a cultural sea change afoot on Wall Street.

Bill

|

|

|

A couple of weeks ago, in correspondence with me, Warren Buffett wrote that he would answer my question about why he had decided to offer the odd number of $848.02 a share, in cash, for Alleghany, the big insurance company he just bought for $11.6 billion. Buffett, being Buffett, was obviously up to something. As it turned out, he didn’t want to pay Goldman Sachs’ $27 million investment-banking fee for advising Alleghany on the sale to Berkshire Hathaway.

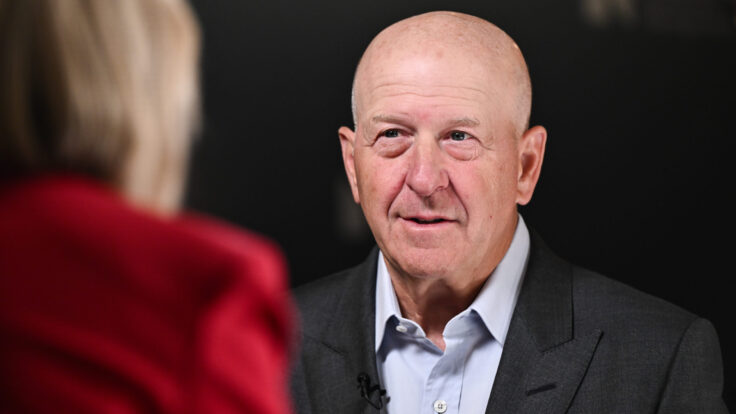

This was quite a turn of events, given that Goldman Sachs has long been Buffett’s preferred Wall Street investment bank. He invested $5 billion in Goldman in 2008 at the height of the financial crisis and his favorite Wall Street banker, Byron Trott, was a longtime Goldman partner before he went out on his own. Plus, the purchaser of a company always ends up paying the seller’s banking, legal and accounting fees one way or the other. Believe me, no buyer likes to pay them, and would prefer not to, but convention is convention, and that’s the way it’s been, and will likely always be.

But Warren Buffett is 91 years old these days and the world’s sixth wealthiest person, with a fortune estimated at $116 billion, and so if anyone is up for tweaking the conventional norms on Wall Street, who better than the most successful investor of all time? Had he not been playing a bit of a game, Buffett would have offered $850 a share for Alleghany. But Goldman’s $27 million fee worked out to that $1.98 per share, and Buffett decided that not only was he not going to pay it, but he was also, in effect, going to force the Alleghany shareholders to pay it by reducing the consideration paid for the company.

When I wrote and asked Warren about why he did this, and what was the point he was trying to make to the wider investment banking community, he replied that he would reveal all at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, held in Omaha last weekend. “Stay tuned,” he teased. But after more than four hours into the marathon session, no one had asked him the magical question. So he decided to ask, and answer, the question himself. (Although I have been a Berkshire Hathaway shareholder since 1991, I have never attended the annual meeting and did not attend this year either.)

Incredibly, for the next 15 minutes or so, Buffett explained the logic for his decision and told a fascinating story about bankers and their fees that forevermore must be part of Wall Street lore. He said he didn’t begrudge Goldman its $27 million fee, per se—though he didn’t mention Goldman by name— and he understands that the fairness opinion rendered by said nameless investment bank was standard operating procedure for a Delaware corporation based upon Delaware law. “They're bound to have to do it because Delaware law was developed in such a way that the directors are protected when they get expert opinions on everything,” he said and then added, in not so many words, that what he did in the Alleghany deal might somehow end up as a case study for Delaware judges or legislators, which could lead to some new laws or new legal precedents. He said that whether the advisory fee was $10 million or $40 million, it made a difference “to someone” and “it has always made a difference to us, as the buyer.” He paused. “But that’s just the way the game was,” he sighed.

|

|

|

He then went back into the annals of Berkshire history and recalled the two times in 57 years that Berkshire had to get a fairness opinion for a deal. In November 1978, Berkshire was in the process of buying Diversified Retailing Company, Inc, a holding company for, among other things, about 75 womens’ apparel stores, then about 47 years old. For reasons having to do with different sets of shareholders, Buffett and Berkshire believed they needed a fairness opinion, or two. Buffett didn’t want to pay the then-going rate for a fairness opinion of about $1 million to $2 million and figured that he and his longtime partner, Charlie Munger, could figure out in “about 10 minutes,” for free, whether the deal was fair or not. (Not that that was particularly relevant given that Berkshire was a party to the transaction.) Furthermore, Buffett had also agreed to vote for the merger only if the majority of the shares voted by the other shareholders of each company agreed to vote for the merger. He turned to Munger and asked him what to do. He worried that one of the investment banks would get the assignment and hand it over “to some guy they hired last week” and then he “writes a little thing” and sticks Berkshire with a $1 million bill. “So what do I do, Charlie?” he said.

Munger said it was simple, and then laid out the plan. Munger advised Buffett to put a list together of 10 prestigious investment banks, top to bottom, based on whatever criteria happened to be relevant to him in 1978. Once he had the list together, Munger advised him to start at the top of the list and call his guy at each bank and tell him that Berkshire wanted to hire him to do a fairness opinion for the Diversified Retailing deal… but that he would only pay the banker $60,000. “Tell him you know it’s an insulting price,” Munger said, “and that it’s ridiculous for him to do it because it will affect what he can get from other people down the line” in the future, for other fairness opinions.

Of course, other clients would question why they should pay $2 million for a fairness opinion when Buffett only paid $60,000. But Munger told Buffett to tell the banker that $60,000 was all he would pay and that “if he’s insulted by” that amount “as he probably should be,” then he’d just go on to the second banker on the list, make the same offer and on and on until he found a banker on the list who would take the assignment for $60,000. If none would, then we would increase the offer to maybe $80,000 and go through the list again until he found a banker to do it for that price. Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

Of course, Munger, an astute student of human nature, was on to something. The first name on Buffett’s list was Jack Shad, at E.F. Hutton, once upon a time a powerful brokerage firm. “Jack Shad was a friend,” Buffett said. (Shad would later become chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission between 1981 and 1987.) He called up Shad. “Jack, I've got this crazy request,” Buffett told him, and then proceeded to butter him up a bit. “I'm going to ask you something that is totally against your interest,” he continued. “And I fully understand the fact that you're going to say [to me] ‘You're an idiot for calling me on this’ and slam down the phone. But I said ‘Jack, here's our procedure. I described this procedure that he gets called first and if he turns it down, then I go to PaineWebber,” and on to the other investment banks on the list until he finds a banker who will do the fairness opinion for the low price that Buffett wanted. “I said, ‘But Jack, you’re the first call.’” Buffett continued, “So $60,000. It's going to screw up your business if you do this because every client you get in the future is going to say, ‘Well, you did it for Diversified Retailing, and Berkshire and why in the world should we pay you $2 million when he paid the $60,000.” Shad didn’t hesitate for a second. “Don't worry about it, Warren,” Shad told him, “I can take care of that. We're in.” Buffett got his fairness opinion for $60,000.

He also needed a second fairness opinion for another set of shareholders involved in the Diversified deal, so he went to the number two player on the list, at PaineWebber, like E.F. Hutton, another important brokerage at the time. Like Jack Shad at E.F. Hutton, the banker at PaineWebber agreed to do the fairness opinion for $60,000. The story caused Munger to joke that the person at each firm doing the fairness opinion for so little money was an “amiable alcoholic” but Buffett said the two banks were very professional and soon enough were able to go back to charging $2 million for a fairness opinion – and these days much, much more. (Goldman will probably make something around $50 million for its fairness opinion representing the Twitter board on its $44 billion sale to Elon Musk.) Buffett added that, a few years later, Berkshire needed a second fairness opinion and went back to the same two firms, who agreed to do it this time for $110,000, what with inflation and all.

|

|

|

Buffett, of course, told the story to make a point about Wall Street fees. “At some point,” he said, “people realize that it's not play money, somebody pays it. And it's a game. But it's what passes muster in Delaware and the directors will have it explained to them by the lawyers that they're not going to get sued if they do it in a certain kind of way. And so I just decided that somebody at some point had to point out what actually was happening in this situation”—the Alleghany acquisition—“and that's why we did it that way and it may go down with our earlier attempts to educate the world on the realities of finance and its various interactions and why it's better to teach your son to be an investment banker than to be an electrician. But you've got an eccentric chairman and that's what he did.”

He then asked Munger, who is 98 years old, for his take, since he had been the one with the original idea to play hardball on investment banking fees. “Well, we’re a little peculiar,” Munger replied, “and all peculiarities are not bad.”

The conventional wisdom on Wall Street about investment banking fees—especially M&A fees, including for a fairness opinion—is that they are an insurance policy for a board of directors. I was just taking Goldman Sachs’ advice, they can say, and even when the fee is big, it’s really quite irrelevant as a percentage of the overall deal. But there’s little question investment banking advisory fees have become disproportionately large, or just too large whether proportionate or not, and that Wall Street banks would happily provide the same service for a lot less money, as Warren Buffett discovered in 1978. Indeed, what Buffett wittingly or unwittingly uncovered was the fact that bragging rights on an important M&A deal are worth far more than the fee being paid, in much the same way that an endorsement from Donald Trump for a MAGA Senate candidate may be worth more than a bunch of donations.

What’s also true is that an M&A fee is nearly entirely profit. There are only minor costs associated with providing advice, and most of those costs—travel, late night car rides, some food—are also paid by the client. True, the often hefty compensation paid to M&A bankers comes out of the firm’s coffers, but most of that compensation is variable and comes at the end of the year and can be ratcheted up or down based on how the year turned out across the whole firm.

Unlike a financing commitment or an underwriting, offering M&A advice puts little capital at risk for a firm, or anything else for that matter except for its reputation, which is not nothing, to be sure. But as we’ve seen over the years, even when you think a seismic event will damage a firm’s reputation—for instance, the London Whale or the 1MBD scandal—it really doesn’t. That’s why M&A is a great business on Wall Street: it provides credibility, has incredibly high margins, and is very hard for the DeFi crowd to disintermediate. I know my former M&A brethren will not want to hear this, but it’s time for the next generation to push for lower advisory fees. What if Elon had put the screws to his bankers on the Twitter deal?

In a subsequent email to me, on May 3, Buffett said that he just had only one regret about what he ended up paying for the Diversified Retailing fairness opinion, nearly 44 years ago. “I should have said $25,000 to Jack,” he wrote, “It may be play money to both sides, but it comes out of someone’s pocket.”

|

|

|

|

| FOUR STORIES WE'RE TALKING ABOUT |

|

| McCormick’s Last Stand |

| Finger-pointing in Dave-vs.-Oz, the House’s Lindsay Lohan, and Geoff Morrell’s Disney crisis comms. |

| TINA NGUYEN |

|

|

| The Smiths' Sorkin Chase |

| Dylan Byers joins Peter to discuss the latest dish on Semafor. Plus, Schleifer on Musk's eccentric financial history. |

| PETER HAMBY |

|

|

| Elon's Eccentric Empire |

| With ingenuity and insane leverage, Musk created one of the world’s most unconventional financial concerns. |

| THEODORE SCHLEIFER |

|

|

| The A.I.-I.P. Supernova |

| Will robots replace us? Who knows. But either way, they're going to learn how to create superhero movies. |

| ERIQ GARDNER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

You received this message because you signed up to receive emails from Puck

Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up for Puck here

Sent to

{{customer.email}}

Unsubscribe

Interested in exploring our newsletter offerings?

Manage your preferences

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC

64 Bank Street

New York, NY 10014

For support, just reply to this e-mail

For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news |

|

|