Welcome back to What I’m Hearing+, Tuesday’s extra cookie dough

topping on your regular WIH frozen yogurt. Two decades ago, back when I practiced law, defamation suits were pretty rare. Even rarer were the libel or slander cases that survived an initial anti-SLAPP motion, and almost nothing made it to trial. Cut to 2025, as Donald Trump has turned media litigation into a political cause, and defamation specialists seem as active as the attorneys for Blake Lively and Justin Baldoni. Today, Eriq

Gardner asks whether the landmark Times v. Sullivan ruling is vulnerable, and, perhaps more provocatively, whether it should be reexamined.

But first…

|

|

|

|

Eriq Gardner

|

|

- AP considers possible Trump suit: We’re nearing the one-month mark of Donald Trump’s second term, and while there’s been plenty of legal action over worker firings, funding freezes, and Elon Musk, not much actual casework related to Trump’s targets in the media. But that could soon change. I’m hearing that the Associated Press may be drawing up a legal challenge to the White House restricting access to AP reporters over its refusal to alter

its stylebook to say “Gulf of America.” During a press conference at Mar-a-Lago this afternoon, Trump castigated the AP for “the treatment of Trump,” and reiterated that its reporters will be banned until the news service adopts his preferred phrasing for the body of water formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico. If the AP proceeds with a suit, it would seem to be on firm legal footing. Look no further than Trump’s first term, when the White House ran afoul of the D.C. Circuit after trying, and

failing, to revoke press credentials for CNN and Playboy.

It’s a bit early to predict whether we’re on the verge of a media litigation barrage, though the landscape might point in that direction. Comcast’s D.E.I. policies are under scrutiny, PBS’s and NPR’s underwriting are being investigated, and the broadcast networks—except, so far, Fox—are being flagged for possible news “distortion.” The mere launch of these probes could prompt court challenges, especially if the media

entities can demonstrate that these actions are retaliation for protected First Amendment speech.

But that doesn’t mean the media will rush to court. If the government’s actions are perceived as mostly symbolic—posturing to appease Trump’s base—these companies might endure the pressure, hoping for a more favorable relationship with the administration. On the other hand, if business interests are genuinely at risk, you can be sure they’ll litigate. After all, Disney sued Ron

DeSantis in 2023 claiming the Florida governor’s repeal of Disney World’s special tax district was political retaliation for the company’s criticism of the state’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill. (Trump sided with Disney against DeSantis in that battle; the parties ultimately settled.) Indeed, I suspect legal fights between media giants and this White House are inevitable, particularly given F.C.C. chair Brendan Carr’s skepticism of media objectivity.

|

|

|

Trump allies sense a more favorable environment for waging lawfare against

media companies, raising the question of whether the Supreme Court might reconsider Times v. Sullivan—and what the media might do to fight back.

|

|

|

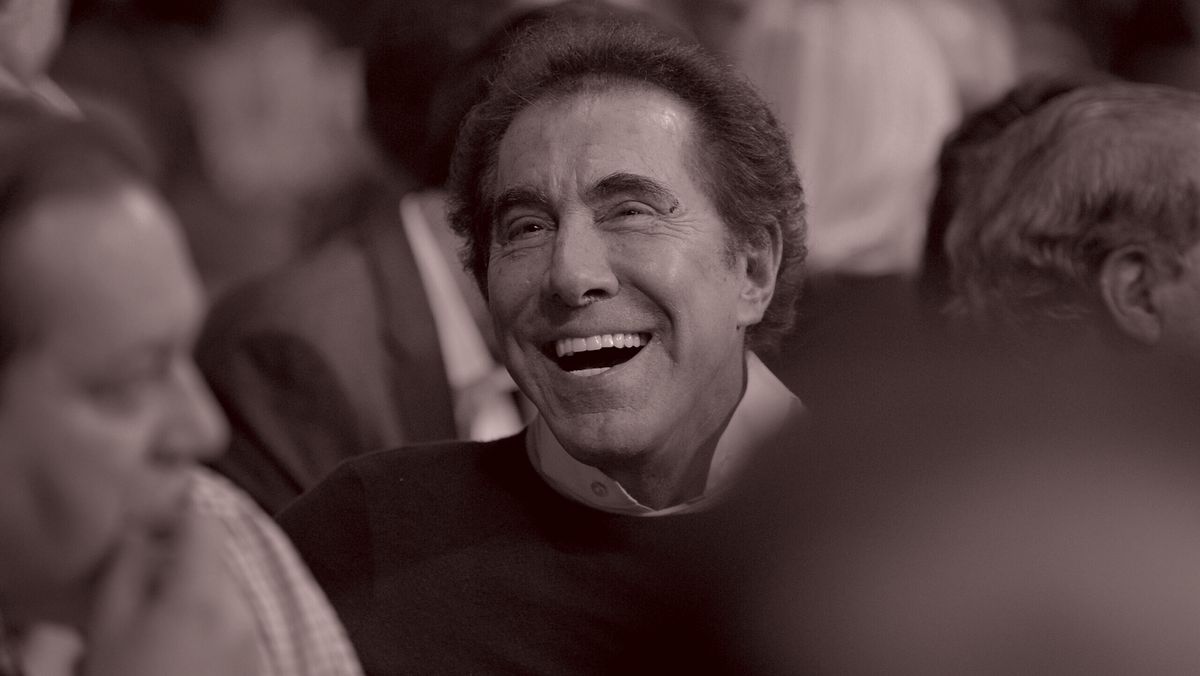

It was only a matter of time before Donald Trump’s newly

empowered allies came after journalists. You could sense the discomfort in media quarters two weeks ago as word spread that casino mogul and Trump fundraiser Steve Wynn had petitioned the Supreme Court to review a defamation case he filed against the Associated Press in 2018. Wynn’s ultimate goal is for the justices to reconsider the “actual malice” standard that public figures must meet to prevail in libel suits, which was established by the landmark 1964 ruling New York

Times Co. v. Sullivan. Journalists—and the U.S. media industry—can be forgiven for worrying that SCOTUS will oblige. Might Sullivan be toppled, much like Roe v. Wade?

I have some difficulty believing the justices will take up Wynn’s case, which stems from an AP story reporting on two women who accused him of sexual misconduct. (Wynn has denied the allegations and was never

charged; a judge ruled that one of his accusers had defamed him.) Yes, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have expressed a desire to overhaul Sullivan, and Brett Kavanaugh has faced sexual misconduct allegations of his own, which he vehemently denied but could make him

sympathetic to Wynn. It’s conceivable that Trump might push for a review through his solicitor general, D. John Sauer, who awaits confirmation. Wynn helped raise $100 million for Trump’s first inauguration, and he was the R.N.C.’s finance chair until stepping down in the wake of the 2018 allegations.

That said, the Supreme Court has declined past chances to revisit Sullivan, with no evident division among the circuits that might force its

hand. Unless, say, the conservative 5th Circuit follows Thomas’s lead and upends six decades of legal precedent by declaring Sullivan no longer good law, that status quo likely remains intact. And given the expected deluge of cases born from the early, chaotic days of Trump 2.0, the likelihood that these busy justices will entertain Wynn’s plea seems even slimmer. If I were placing bets in a Wynn casino, my money would be against him.

|

As for whether the U.S. should reassess the actual malice standard

articulated in Sullivan, well… that’s a separate question. Perhaps it’s surprising to read this from a journalist, but maybe Justice Gorsuch was onto something when he noted that changes might be needed to account for this current era of internet-enabled media where anyone can climb atop a digital soapbox. Is our current legal framework the best we can do?

This isn’t about being contrarian. Sullivan was a solid response to a particularly absurd lawsuit of its time. In 1960, the Times was sued over a full-page ad taken out by civil rights activists. L.B. Sullivan, an Alabama police commissioner, claimed defamation even though his name never appeared in the ad. An all-white jury (and an openly racist judge) awarded Sullivan

$500,000 in damages. In response, the Supreme Court sought “breathing space” for the First Amendment, adopting a rule requiring public officials to prove that a defendant had knowledge of falsity, or at least a high degree of awareness of a claim likely being false, in order to collect damages.

This standard was later extended to others in the public sphere, effectively shielding U.S. media from

substantial defamation losses for more than half a century. Sullivan has also been explicitly codified into the libel laws of several states, including New York. So even if the 1964 ruling were overturned, public figures claiming libel would still need to demonstrate actual malice, among other things, to prevail in courtrooms throughout much of the country.

However, the media

ecosystem is different today than it was in the 1960s. Disinformation is rampant online, tech companies have scaled back content moderation, and journalists face the prospect of expensive legal battles in unfriendly jurisdictions like Texas and Florida. Judges have allowed questionable libel suits to proceed—for example, last week a Florida court gave Trump permission

to sue 19 members of the Pulitzer Prize board for “defamation and conspiracy” over their refusal to strip The New York Times and Washington Post of Pulitzers awarded for their reporting on Russian election interference. Perhaps not surprisingly, when the media itself is on trial, plaintiffs feel justified in asking jurors for massive punitive damages. Recall that, just a few weeks ago, CNN chose to

settle with a Navy veteran who sued over its Afghanistan reporting—after his lawyers demanded $150 million in damages.

All this points to a problem that the Supreme Court encountered in Sullivan but didn’t really solve: the burden that media companies face in certain

far-flung corners of the nation. Defending free speech in hostile territory continues to be a challenge, 60 years after Sullivan. These days, savvy plaintiff lawyers shop for advantageous forums, and legal defense costs have soared. One can make the case that the actual malice standard, intended to protect journalists, now exacerbates these issues by focusing on a reporter’s state of mind, leading to invasive and costly discovery. This nuisance, unfortunately, too often serves as its

own deterrent to publishing anything controversial.

To counter the rising specter of well-resourced individuals filing meritless, speech-chilling lawsuits, many states have passed anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) laws, which provide early judicial review of cases to filter out the frivolity. However, significant gaps persist, especially in federal courts across much of the South.

Indeed, anti-SLAPP laws themselves have come under legal challenge. For instance, on the undercard of Wynn’s petition to the Supreme Court, he’s arguing that Nevada’s anti-SLAPP statute infringes his constitutional right to a jury trial.

In light of all this, would media organizations trade the malice standard for other safeguards—such as a federal anti-SLAPP statute, a cap on damages, legal reimbursement for B.S. cases,

stricter controls on forum-shopping, and safe harbors for issuing corrections? If there is an appetite for broad reform as part of a dialogue about digital misinformation and Section 230, perhaps relitigating Sullivan shouldn’t be completely out of the question. Maybe there’s a better approach.

|

Of course, one objection to any reexamination of Sullivan is that no

trade-off is actually on the table. Eliminating the actual malice requirement alone, particularly during the Trump administration, might seem like discarding one’s belt in anticipation of suspenders someday returning to vogue. Few politicians are advocating for reforms that could ostensibly benefit the press.

This points to another issue with Sullivan—it’s increasingly seen as a shield

for media elites. But this is a small-minded interpretation. Recall that the actual malice standard was originally implemented as a broader civil rights safeguard. The First Amendment protects more than just big media companies, and any rule designed to provide free speech with “breathing space” for errors should be viewed as a universal benefit, not just a privilege for journalists.

The

challenge, naturally, is getting skeptics to acknowledge the need for further reform. One approach could be to strategically flip the script: to put those skeptical of speech protections on the defensive. For example, if Elon Musk can sue over accusations of Nazi sympathies, why shouldn’t government employees, and others who believe themselves maligned by his tweets, sue Musk for calling them frauds? (To quote my partner Bill Cohan, this is not legal advice.)

Media organizations might also benefit from taking a more proactive stance. Traditionally focused on defending their right to publish, perhaps it’s time they also vigorously defend the reputations of those who do. Given the emergence of A.I. and the proliferation of what law professor Eugene Volokh once called

“cheap speech,” there may be additional arguments for media entities—even streamers like Netflix—to more assertively prosecute their credibility. This might mean suing when critics suggest they are being unprofessional.

So what

might this look like in court? Consider E. Jean Carroll’s defamation case against Trump, financed by billionaire Reid Hoffman, which resulted in an $88 million judgment across two trials. Could journalists similarly accused of fabricating stories pursue vindication in the same manner? Should groups like the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, or the ACLU, support libel actions brought by reporters? How about profit-motivated funders of

litigation?

While this may all escalate into lawfare, a compromise seems attainable—one that reacquaints society with the value of speech protections and fosters a dialogue on which policies best address disinformation and libel tourism without rising to censorship on one hand and lies without consequence on the other. Of course, such a resolution won’t emerge from a single Supreme Court petition, but it may be

premature to dismiss the possibility that nothing good can possibly come from a new paradigm.

|

Thanks, Eriq. I’ll be back on Thursday. See you then.

Matt

|

|

|

Puck founding partner Matt Belloni takes you inside the business of Hollywood, using exclusive reporting and

insight to explain the backstories on everything from Marvel movies to the streaming wars.

|

|

|

Unique and privileged insight into the private conversations taking place inside boardrooms and corner offices up

and down Wall Street, relayed by best-selling author, journalist, and former M&A senior banker William D. Cohan.

|

|

|

|

|

LAUREN SHERMAN & RACHEL STRUGATZ

|

|

|

Need help? Review our FAQ page or contact us for assistance. For brand partnerships, email ads@puck.news.

You received this email because you signed up to receive emails from Puck, or as part of your Puck account associated with . To stop receiving this newsletter and/or manage all your email preferences, click here.

|

Puck is published by Heat Media LLC. 107 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10006

|

|

|

|