|

Good afternoon,

I'm William D. Cohan, the author of six books and a former M&A banker. Welcome back to Dry Powder, my private email about what's really happening on Wall Street. If you haven't yet had the chance, you'll need to subscribe to Puck to read my latest column in full.

As a reminder, you can always manage your newsletter settings on the Puck website. My colleague Dylan Byers has a new offering, In the Room, about what's really going down in the corner offices of the most important media companies. If you're interested in the technology and entertainment industries, I highly recommend adding it to your subscription.

Today, I'm digging through my inbox and opening my reporter's notebook to answer some of the most pressing questions on Wall Street this week, and sharing a preview of my responses, below. If you're enjoying what you're reading you can become a full member here.

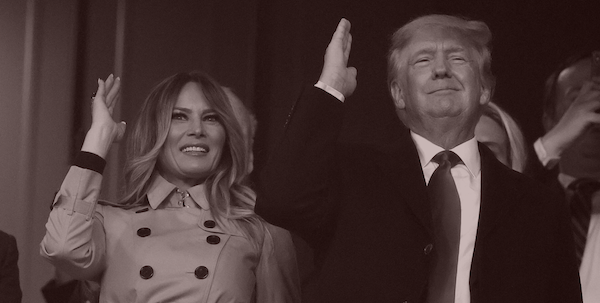

Since I began writing my column for Puck, I’ve been inundated with feedback about Wall Street’s biggest characters and concerns. I’ll be engaging with some of those questions here—in addition to a few observations of my own. DWAC, the blank-check vessel for Donald Trump’s nonexistent media venture, has tumbled from its meme-stock highs to settle at about $70 a share, still more than a 570% return for early investors. The total windfall for the SPACs obscure financiers could stand at about $440 million, according to the WSJ—what is it about the structure of this SPAC that is so remunerative for its sponsors?

With the notable exception of a SPAC put together by hedge fund manager Bill Ackman—which remains, at $4 billion, the largest SPAC I.P.O. to date and that has yet to be de-SPACed (i.e. that has found a merger partner)—most SPAC sponsors tend toward the greedy side of things. They literally pay pennies on the dollar for the stock they receive as they are setting up the SPAC. Their first windfall comes when the SPAC goes public. Their second windfall comes when they announce a deal to merge with a private company (assuming, of course, that investors react positively to the announced deal).

So, in the case of the aforementioned DWAC, its principal sponsor, Patrick Orlando, an erstwhile Wall Street trader, paid all of $25,000 for his 8.6 million DWAC shares. When DWAC went public, at $10 a share in September, Orlando’s 8.6 million shares were worth $86 million, an increase of only 343,900 percent. (That is not a typo.) When Orlando announced the merger with Trump’s “nonexistent media venture” a few weeks ago, the DWAC shares climbed as high as $175 a share for no other reason than lunatic investors piled into the stock because Trump was involved. That made Orlando’s DWAC stock worth—briefly—$1.5 billion. Talk about alchemy. Orlando turned $25,000 into $1.5 billion in a few months, thanks to the investors who have allowed SPACs to survive by buying their shares. How ridiculous is that? Now, with the stock down to $67 a share, Orlando’s stock is worth $576 million. He won’t be able to sell any of his DWAC stock until six months after the deal with Trump closes, if it closes at all. (A previous deal Orlando struck in another of his SPACs—he has four now—collapsed last month, and there are already questions about whether the Trump SPAC violated securities laws.) So for now his astronomical gains remain on paper. No wonder sponsors are willing to form these SPACs. The question for me remains, why do investors agree to go along with these utterly one-sided structures? That’s the real and ongoing mystery.

Lloyd Blankein, a longtime liberal, seemed sullen in his interview with Bloomberg that he may never get his shot at serving as Treasury Secretary, given the new politics of the Democratic Party. Are the days of big bankers like Rubin and Paulson taking a spin in Washington over?

No, I don’t think they are over, but they may be over for Lloyd in an administration that throws bones to its progressive wing through its cabinet appointments, and may not want to deal with the politics (or at least the optics) of making the former Goldman C.E.O. the next head of the Treasury. And he wouldn’t be the first Wall Street C.E.O. frustrated at being passed over. Steve Schwarzman, the co-founder of the Blackstone Group, must have been immensely annoyed that Trump—despite Schwarzman’s ongoing public support—stuck with Steven Mnuchin at Treasury for a full four years.

But Treasury is one of those positions that will always go to someone who knows more than a little something about banking, finance or business. As it should be, to some extent, or else it would become too friendly to the private sector. Janet Yellen, the current Treasury Secretary, is a brilliant economist, and the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, who also happens to not be a billionaire white guy, which makes her a perfect choice, professionally and politically.

Many on Wall Street suspect that Yellen’s successor is likely to be another woman, such as...

FOUR STORIES WE'RE TALKING ABOUT With the Chappelle uproar, Netflix has become an unwitting signpost in the culture wars. Some believe it may presage a turning point. MATT BELLONI Members of the intelligence community are increasingly convinced that the Russian government is behind the "Havana Syndrome." JULIA IOFFE In the middle of perhaps the most consequential scandal of his career, Mark Zuckerberg unveils his new vision for the metaverse. DYLAN BYERS The formative years of David Zaslav's career explain as much about the history of cable as they portend about the future of streaming. WILLIAM D. COHAN

|

-

Join Puck

Directly Supporting Authors

A new economic model in which writers are also partners in the business.

Personalized Subscriptions

Customize your settings to receive the newsletters you want from the authors you follow.

Stay in the Know

Connect directly with Puck talent through email and exclusive events.